In Haystack, Mountains and Waterlilies, Jennifer Cho mobilizes “Slow Art” to articulate the need for sensuous and sensible vigilance within art-making. The exhibition is an ecology of built forms, a simulacra—a made up ecosystem that offers a view of a world proximate to our own.

It fuses warm atmosphere with conceptual elegance, drawn from outworn materials. The installations delight and enchant while destabilizing what qualifies as a landscape. In Haystack, Mountains and Waterlilies, all five senses are employed with grace and acerbic wit, balancing consistency with surprise. Cho inhabits the painterly practices of Cezanne, Monet and Millet, transporting their intensely embodied preoccupations with landscape onto her own artistic concerns. Complicated and subtle, the exhibition excavates the sedimentary layers of technology that develop a scene of both intimacy and ignorance; technology we entrust with our most vital choices and secrets.

“Haystack” (2000-2023) is a ghostly, crystalline work carved from soldered compact discs. The term “Slow Tech,” coined by Jennifer Cho, enlists rigid, glittering forms that resemble a natural haystack. Extravagant yet tranquil, the work triggers a human nostalgia for a primordial state of cultivation, as art objects are culled from the natural world. Like Jean-Francois Millet (1814-1875) tributes to endurance of unrewarded toil for peasants, unspooling the strands of the compact disc requires careful, assiduous work. Taking the time to unfurl these strands, Cho engages in an epic struggle with seemingly slight and minuscule material.

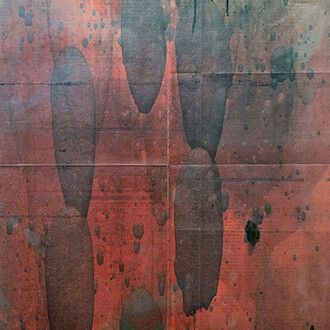

To raise “Mountains” (1995-2023), Jennifer Cho inhabits the practices of Jeong Seon (1676-1759) and Paul Cezanne (1839-1906). While these artists walked through the respective mountains of Mt. Kumgang and Mt. Saint Victoire, they used their footsteps as a way to physically and psychologically register the scene they were about to paint. Cho transposes that footwork into handwork, creating a delicate, melancholy rendering of “Mountains.”

Haunting and menacing, “Waterlilies” (2000-2023) erects shallow pools at the center of a gallery room containing Siamese fighting fish and floating compact discs. Hazy and textured, the clear water grows progressively murky as fish dart around the pond. The work interlaces narrative with fantasy, developing a false ecosystem from fish and obsolete technology that nonetheless teems with life. The result is an otherworldly biome that seems to exist outside of time and space—an altered reality.

Haystack, Mountains and Waterlilies confers the history of landscape as a long arc, connecting Asian landscape to European plain air works, to Contemporary Art. In these respective works, history provides the framework for new matter, as ostensibly obsolete technology is re-released as mountains, flora fauna, and water. The exhibition persuades for a fresh conceptualizing of time, asserting a vision of history less as a linear progression but more as a topography whose past is layered within its present material. The beauty of the physical universe is not an illusion of human eye and the rest of the human sensorium, but a true glimpse into the inner nature of things. Daring to look at works of art in the flesh, Jennifer Cho sees the landscape both in its beauty and in its terror.