Famously, the American Abstract Expressionists of the 1950s increasingly pursued a humanist purview, albeit in myriad directions. On the one hand were those like Rothko (1903-70), Gottlieb (1903-74), and Newman (1905-1970) who, drawing from myriad philosophical influences, pursued the possibility of transcending the human condition by way of the “sublime”—the paradoxical experience of being simultaneously overwhelmed and exalted. While these artists adopted a penchant for color field painting, other Abstract Expressionist compatriots in the 1950s, such as Willem De Kooning (1904-97), Franz Kline (1910-62), and Lee Krasner (1908-84) drew their attention to the anguish and banality of the human psychological condition through the use of the abstract gesture.

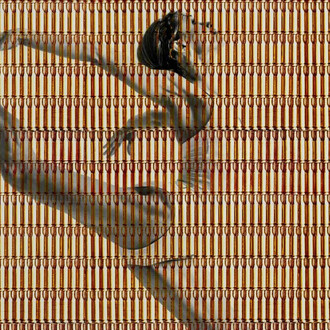

Alberto Murillo (b. 1974), a self-taught painter who began his career in interior design, gives us paintings which are closer to the first tradition than the latter. Interior design is perhaps the most marked non-art historical force detectable here, however—these works, upon a quick glance, have a clean arrangement to them that is markedly domestic. Yet rather than incorporate textile products plucked from the home, Murillo embraces novel types of industrial aesthetics valued for their extra-aesthetic properties and utilitarian potential. Works like Red Dust and UnderWater— the former being acrylic on canvas and the latter high gloss enamel on canvas—utilize vibrant, glistening panels in blocked arrays that unspool architectural vim and structural cohesiveness. There is a certain neatness to these works that reminds viewers of Claes Oldenburg and Eva Hesse, both of whom, like Murillo, experimented with the structural (and, thus, sculptural) potential of vinyl and fiberglass. Unlike the aforementioned twentieth century artists, however, Murillo's compositions are redolent of the architecture of Spain—for me, it is Spanish Colonial Revival architecture that most readily makes itself known in these works; not through any structural similarities but through sun-kissed palettes and plates of sea-swept blue upon sand-bitten apricot planes.

Yet another critical influence is that of Pop Art, which is squared not in the aesthetics of the sublime nor the phenomenology of painting, but that of reappropriation. The great art critic and philosopher of art, Arthur Danto, asked the question why an object, such as a Brillo Box, which in any other environment would not be recognized as an art object, is received as such in the gallery context? The answer, albeit more involved than this reductive rehearsal, related to the “art world” and its myriad theoretical resources, as well as the gallery/art-institutional framing. Murillo, however, does not give us any such direct resources which point to objects that we would encounter out in the world and are appropriated with such ontological queries to boot. It is, instead, the clean-edged, hard-nosed aesthetics of Pop Art which infect Murillo’s paintings. In some sense, Murillo’s proximity to both Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art brings him closest to the world of artists like Claes Oldenburg who, in works like his 1960s series of Candy bars, dovetails the prismatic, splatter-strewn rivulets of Abstract Expressionism with those of recognizable Pop Art motifs. Such commercial products and their coeval seep through Murillo’s own art practice, albeit ushered into the twenty-first century. Indeed, while works like American Pride (2017) recall Jasper Johns' own renderings of the flag, Murillo discerns his art practice from conceptual artist like Michael Bidlo and Richard Prince, who appropriate the appropriators, by way of color schemes, such that it is not the ontological question that looms large but an aesthetic one. American Pride, for instance, features an uneven, azure, almost milky-blue field upon which the fifty stars are strewn, discerning it from Jasper’s flags. This is, perhaps, the most readily "Pop Art" piece in Murillo's cannon, although works like Ray of Sunshine (2022) and Siesta del Sol (2022) do recall the flat, two-dimensional commercial aesthetics that populate myriad advertising platforms—particularly those of our new media digital epoch.

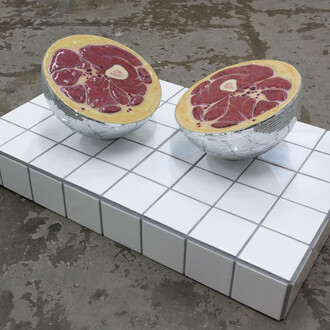

Murillo’s paintings are also soothing. The surfaces often contain carved slivers: hoary grays, tangerine oranges, and cascading marrons. These slivers are almost rainbow-like boxes—little sets furnished with acrylic or polymer emulsion that, in the artist’s own works, “are liquid skins that can be pulled, pushed,” before being coated with resin. The finished product is crisp and luminescent—far from the world of natural beings and organic elements, these almost appear to be digitally rendered. Works like My Japanese Garden do, admittedly, at times, point to the natural world: the pear-like shapes could either be garden stones or fruits ready to pluck and table. The array of color fields that are layered on top of one another, however, prod these quasi-fruits/stones quite far from the empirical realm of natural objects. Mustard yellow and dusted brown shavings splinter and intersect. Murillo’s work, compendiously exhibited at Kate Oh Gallery, show a distinctively novel direction for abstraction today.

(On the Aesthetics of Interior Decoration as Abstraction, Text by Ekin Erkan)