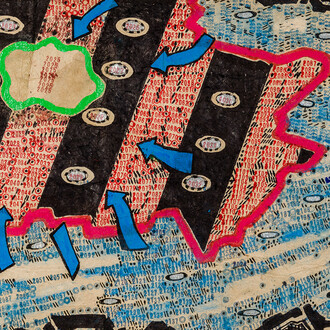

In many ways, Arian Lori-Amini (Hypnotiq Design) is the pop artist par excellence of the day. The artist, hailing from Seattle’s tech industry, uses 3D printing and UV resin, alongside more traditional sculptural material, to create neon-bedaubed works that replicate popular media artifacts. These include Louboutin boots, a Marilyn Monroe bust, skulls, a panther, Campbells tomato soup cans, gorillas, or Jeff Koons-esque balloon dogs. Each work is glassy, glazed, and reflective, abounding with cherry-red crimsons and cobalt blues.

Some of these works point towards Pop Artists past and present—most notably, Andy Warhol. To trace this relationship, we must first consider the sources from which Hypnotiq draws. One such starting place is Hypnotiq's Shahyad Tower - Shah's Memorial Tower (2020). The artist, who is originally from Iran, was a young boy living in Tehran during the Iranian Revolution of 1978-9. He often notes that this was a seminal experience for him. The bright, flashy coral and azure drips that adorn the small-scale replica of the monument located on Azadi Square in Tehran are, according to the artist, not merely decorative but also indices of explosions and brittle witnessed first-hand. Hence, the Azadi Tower is recreated with graffiti-like paint splatches. Yet rather than imbue these recreations with melancholia, the artist's penchant for flashing variegated colors is of a piece with a particular West-coast finish, an aesthetic that is redolent of 1OAK rooftop balcony parties and the tepid, bubbling Le Bain pool that clubbers perch in as they sip vodka redbulls.

If the artist is interested in culling the Iranian Revolution—stripping the popular uprising against Mohammad Reza Shah's regime and the populist appeal of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of its sociopolitical purpose by, instead, reifying this event through the eyes of a naive child—then the aesthetization of debris, refuse, and detritus can perhaps be most closely identified with pop art works such as Andy Warhol's 1964 Electric Chair. There is no commentary about the Shah in this piece just as Warhol did not necessarily criticize the death penalty. Notably, however, this is the work that is most overtly tethered to Hypnotiq’s reported experience of witnessing the Revolution first-hand, making the work somewhat more personal than Warhol’s experience with the electric chair—after all, in Warhol’s case, the silkscreen work, which was part of the “Death and Disaster” series executed between late 1964 and 1965, replicated a found image. Hypnotiq, on the other hand, insists that his experiences during the Iranian Revolution inform his choice to use the splatter-paint motif, even in works that reference popular culture instead of historically significant icons. In turn, this brings to bear another commonality between him and Warhol: the post-modern ambivalent stance.

A current running through much of Warhol’s work, taken up by many art historians and critics over the last few decades, is whether Warhol was launching a criticism of consumer culture or merely celebrating popular aesthetics? The latter option is politically feeble, hailing the death of criticism (in parallel to Lyotard’s proclaimed death of grand narratives) while underscoring the simultaneously commonplace and extravagant aesthetics of mid-to-late twentieth century commercial culture. If we adopt this interpretive approach, Jackie O, Marilyn Monroe, Campbell’s Soup, Mao, and even the electric chair are stripped of sociopolitical and historical weight and, instead, presented in silkscreen form as adorned, visually stimulating icons. Thus unspools the birth of the iconic as such. Granted, even this politically de-tasked mode, wittingly or not, presents a mirror to consumer society and, consequently, allows for viewers to adopt the critical position. This offers for myriad analyses. For instance, subsequent theorists have drawn our attention to Warhol’s life-long devout Byzantine Catholicism and the strong impression that the Christ icons adorning the Ruthenian Greek Catholic church in Polish Hill, Pittsburgh had on young Warhol. Others, like Douglas Crimp, have spotlighted Warhol’s queer identity, turning to markedly queer works like Warhol’s 1964 film, Blowjob.

Similarly, one might query if Hypnotiq's Iranian identity and, more markedly, his witnessing the Iranian Revolution, might offer us a critical position with which to approach the Western media images that his sculptural practice centers. Rather than offering mere replicas, both the sculptural works and the Instagram-photo presentation of these sculptures are polished and, in turn, retain a technological sensibility to them. The Campbell’s soup cans, now in Hypnotiq's hands, become lustrous and sleek, like airbrushed digital images. This is fitting, given that the analog media of Warhol’s day has been displaced by the ubiquity of contemporaneous digitality. Hence, if Warhol was the 20th century pop artist par excellence, offering us a mirror to critically observe the celebrities and media icons we were once usurped by, Hynotiq cedes us a glossy digital selfie, imbricated with present-day personages that range from Kim Kardashian to Steve Aoki. Regardless of whether Hynotiq’s art practice is intended to criticize capital and consumer culture or, alternatively, willingly participate in it vis-à-vis glorifying and extending its aesthetics, we as postmodern viewers can situate them within our present-day milieu and prod forth such critical queries which, ultimately, rest in the seat of the interpreter.

(Written by Philosopher and Art Critic Ekin Erkan)