Primarily known for paintings based on historical Chinese photographs, Hung Liu’s paintings of the past few years have been inspired by photographs of American documentary photographer of the Dust Bowl and Depression, Dorothea Lange, whom Liu has long admired. Having grown up in revolutionary China, and enduring the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, Liu is familiar with landscapes of epic social struggle and displaced humanity.

In “This Land …,” her show of recent paintings, from October 24 to December 7, Liu continues her focus on Lang’s subjects as they migrate across America in the 1930s in search of work, dignity, and salvation. Though it invokes the title of Woody Guthrie’s anthem of 1940, written as a rejoinder to Irving Berlin’s “America the Beautiful,” the title of Liu’s exhibition, “This Land …,” does not offer the visions of sweeping vistas – the ribbons of highway, the golden valleys, the diamond deserts, or the wheat fields waving – but a landscape of broken down cars, flattened tires, stranded and damaged and hollow people, tarpaulin and cardboard shacks, a harvest of bitter onions. “This Land …,” like the ellipsis in the title, indicates an omission, all that America the beautiful was not.

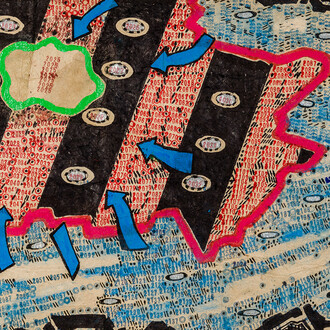

Liu’s painting style, with its fluid washes, expressionistic brushstrokes, and eroding photo-based images, has often been thought of as a kind of weeping realism – especially when applied to Chinese subjects. Reacting against the rigid techniques of Chinese Socialist Realism, in which she was trained, Liu’s hand has deftly engaged her subjects, turning old photographs into new paintings, and anonymous figures into dignified individuals. For her Lange-inspired works, Liu has developed a kind of topographic painting technique in which she “maps” an image with colored lines, the richness of which belies the real-world poverty of her subjects. What emerges is a kind of vascular web of color that holds the images, especially those of people, more firmly in place. Liu thinks of these webs as cracks of light breaking through, an homage, perhaps, to Lange, who was working to change the plight of the migrants she photographed.

While the larger new paintings confidently combine Liu’s traditional weeping realism and her more recent topographic mapping, the smaller ones – the “Duster Shack” series – are richly expressionistic improvisations that seem bigger than they are. Also taken from Lange’s photographs, they depict ramshackle shelters cobbled together by migrants who have nowhere to lie down except where they happen to find themselves at day’s – or road’s – end. The mineral mix of the paint and colors are almost analogues for the mix of materials – boards, blankets, old tires, even cars – that compose them. The term “Duster” refers here to refugees from the Dust Bowl.

The human figures depicted in the larger painting are mostly studies in dejection, with several instances of stolen affection or unexpected gratitude. Of this latter, a woman, perhaps Mexican, holding a baby looks upward and smiles as they sit beneath the crotch of a cottonwood tree. One feels they have just crossed a river, or that the baby is newly born. Beside the woman’s head, attached to the canvas, is a head-size gold-leaf oval, invoking the idea of portraiture and elevating the portrait to the status of an icon – perhaps as the Virgin of Guadalupe. At this moment, an unpublished stanza from Guthrie’s song echoes back through time to the present:

There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me; Sign was painted, it said private property; But on the back side it didn’t say nothing; This land was made for you and me.

Hung Liu was born in Changchun, China in 1948. She grew up in Beijing during the revolutionary era of Mao Zedong. In 1968 she was sent to the countryside for four years during the Cultural Revolution where she worked with peasants in rice, wheat, and cornfields seven days a week. During this time, she photographed local farmers with their families and also made drawings of them. After returning from the countryside, she entered the Revolutionary Entertainment Department of Beijing’s Teachers College to study art and education. In 1979 Liu attended the Central Academy of Fine Arts where she majored in mural painting. In 1980 she applied to the Visual Arts graduate program at the University of California, San Diego. After being accepted, it took Liu four years to obtain a passport from the Chinese government. She arrived in California in October 1984.

A two time recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in painting, Liu has exhibited throughout the nation and beyond. A retrospective of her work, “Summoning Ghosts: The Art and Life of Hung Liu,” was organized in 2013 by the Oakland Museum of California, and toured nationally through 2015. In a review of that show, the Wall Street Journal called Liu “the greatest Chinese painter in the US.” Liu’s works have been exhibited extensively and collected by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Nelson Atkins Museum and the Kemper Museum, Kansas City, the Dallas Museum of Art, the Denver Art Museum, the Palm Springs Art Museum, the National Gallery of Art, the National Museum of American Art, and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., the Asian Art Museum and the De Young Museum of San Francisco, as well as the San Jose Museum of Art, among others. Liu currently lives in Oakland, California. She is Professor Emerita at Mills College, where she has taught between 1990 and 2014. In 2021, Liu will be honored with a retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.