The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), presents Laura Owens, the much-celebrated and highly anticipated survey exhibition of paintings by Los Angeles-based artist Laura Owens (b. 1970, Euclid, Ohio). Organized at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, by Scott Rothkopf, Deputy Director for Programs and Nancy and Steve Crown Family Chief Curator with Curatorial Assistant Jessica Man, and overseen in Los Angeles by MOCA Senior Curator Bennett Simpson with Assistant Curator Rebecca Matalon, the exhibition will be on view at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA from November 11, 2018–March 25, 2019.

Building on MOCA’s longstanding commitment to Owens, this exhibition is the most comprehensive since the artist’s landmark early survey at the museum in 2003. Laura Owens, featuring approximately 60 paintings from the mid-1990s to the present, highlights the significant strides Owens has made in recent years and shows how her early work sets the stage for gripping and groundbreaking new paintings and installations.

”Laura Owens is one of the absolutely crucial figures in the development of painting over the past three decades,” says Simpson. “Her sense of experimentation, including but surpassing questions of technique, has been highly influential and a wonder to behold. Laura’s history is deeply entwined with the history of this museum, and it is an honor to bring this acclaimed exhibition to Los Angeles.”

For more than twenty years, Owens has pioneered an innovative approach to painting that challenges traditional assumptions about the nature of figuration and abstraction; the relationships between avant-garde art, craft, and pop culture; and the interplay of painting and contemporary technologies. Owens emerged on the Los Angeles art scene shortly after completing her studies at the California Institute of the Arts in 1994, at a time when the academic establishment viewed painting with skepticism and many of her peers favored more conceptual approaches to artmaking. Owens bucked this prevailing trend with a series of large-scale canvases marked by grand ambition on the one hand, and the incorporation of humble, low-key marks and subjects on the other; she merged abstraction with goofy personal allusions, as well as materials that seemed more the province of craft stores than the fine arts. References to cartooning, doodling, and a high-pitch, sometimes pastel, palette served as further irritants to ingrained painterly pieties.

Over the ensuing decade, Owens established herself as a key voice, pushing painting toward a new conception of site-specificity grounded in the social, poetic, and architectural conditions of a particular place. Early on, she demonstrated a keen interest in how paintings functioned in a given room and used trompe-l'oeil techniques to extend the plane of a wall or floor directly into the illusionistic space of her pictures. These canvases often featured paintings within paintings, sometimes with paintings nestling within those, creating a mise en abyme effect that confused the boundaries of actual and pictorial space, as well as those of reality and representation. Owens's approach offered a highly original conception of how a portable painting might allude to its initial setting (and its siblings in a series) while nevertheless remaining distinct from it, unlike the in-situ wall paintings of previous generations. These works demonstrate a self-conscious and reflexive relationship to the physical world they occupy while opening, almost paradoxically, onto a lush space of reverie, conjecture, and play.

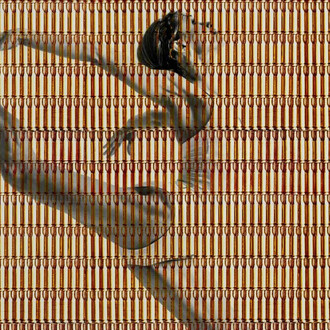

Owens's interest in American folk art, historical tapestries, and other vernacular forms led her to fill her canvases with imagery and materials, such as felt applique and needlework, that were anathema to more serious discourses on painting and some of her critics. This omnivorous approach to source material and technique allowed Owens to push painting forward and engage broader social issues in surprising ways. In the aftermath of the United States's call to war following the events of 9/11, Owens turned to almost childlike depictions of 19th-century American soldiers and images of medieval knights to address our increasingly bellicose national conversation. Her longstanding preoccupation with supposedly "feminine" colors and motifs, such as charming animals and infantile gestures, as well as allusions to romantic love and motherhood (including the incorporation of her own children's drawings and stories) within her work has led to a disruptive rethinking of feminism in art. Owens regards her questioning of the dominant hierarchies and conventional notions of "good taste" as a feminist reappraisal of artistic orthodoxies.

Over the past five years, Owens has charted a dramatic transformation in her work, marshaling all of her previous interests and talents within large-scale paintings that make virtuosic use of silkscreen, computer manipulation, and material exploration. Wild, blown-up brushstrokes push off finely printed appropriations from newspapers and other media sources; actual wheels or mechanical devices, such as clock hands, spin across a painting's surface; images shuttle between the physical and virtual worlds to arrive back on the canvas. In a 2015 Berlin exhibition, Owens precisely positioned a group of five large freestanding paintings in a staggered row so that from a specific vantage the writing on their surfaces resolved into a unified image in the eye. The following year she created an installation at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts in San Francisco with paintings embedded within walls covered in custom-printed and hand-painted wallpaper. Owens encouraged visitors to interact with the installation by sending text messages to various numbers that triggered elliptical spoken replies broadcast by hidden speakers. Such bold experimentation with painting, sculpture, technology, and process have made Owens an important exemplar for younger generations of artists, many of whom cite her work as a key touchstone. Furthermore, she was a cofounder of 356 S. Mission Rd., a collaborative art gallery, bookstore, and event space that hosted regular exhibitions, readings, and screenings, and was a crucial gathering place and a beacon for the Los Angeles art community prior to its closing in June 2018.