Between the abyss of cliffs, the summits of mountains and the spring-fed basin of Lake Atitlán, indigenous communities such as the Tz’utujil of Sololá, Guatemala, continue to preserve the ancestral Maya knowledge that governs the cosmos, grounded in a profound relationship with nature and with the energies understood to animate and constitute all life forms. Anchored in an artistic practice that looks to reclaim the poetic wisdom of his ancestors and their connection with the universe and its creation, Manuel Chavajay presents Rupeequul kaajuleew / Vientre de los cosmos (the womb of the cosmos), his new exhibition at Galeria Pedro Cera’s Lisbon branch and his first solo presentation in Portugal.

In contrast to Western epistemologies historically shaped by scientific objectivism and linear rationality, Maya cosmology is structured through a mythical framework in which primordial events and history are understood as cyclical and interdependent. Within this worldview, thought and action remain connected to ancient origins, accessed through divine knowledge transmitted via dreams and visions shared with those who came before, for whom Earth flourished as a spiritual center regulating time and the rhythms of existence. Its essence was shaped by an astral relationship with celestial bodies, visible at different moments of the year, from which auspicious days for rituals and agricultural activities were determined, as well as the energetic forces believed to guide destiny and the synchrony inscribed in the nawal, the symbolic guardian power associated with each day. Structured through overlapping ceremonial practices and calendars, Maya timekeeping articulated a method of reckoning based on the movements of Earth’s rotation, revolution and precession, the alignments of solstices and equinoxes, and the trajectories of the Sun, the Moon, Venus (the “Great Star”), the stars and comets.

Rejecting linear and teleological definitions, Chavajay departs from this cosmological framework to situate Rupeequul kaajuleew / Vientre de los cosmos within the logic of the Maya Tzolk’in ritual system. Composed of a 260-day continuous cycle created through the repetition of 20 sacred nawal across 13 galactic iterations (20 x 13 = 260), the Tzolk’in establishes a correspondence between the empirical world and ancestral understanding of the universe. Associated with pan Mesoamerican practices and developed by civilizations such as the Zapotec of the Valley of Oaxaca around 600 BCE, this lunar calendar reflects spiritual and numerological networks that connect celestial movements and the passage of the zenith at certain altitudes – factors that define the energetic pattern of each Jun Winaq (Tz’utujil for ‘individual’ or ‘person’), comparable to a Western horoscope – while further referencing the orderly systems regarded with the number of digits used in manual counting (20 in total, ten on the feet and ten on the hands), the human body’s principal articulations (13 in total, including the neck, the two shoulders, the two elbows, the two wrists, the two hips, the two knees, and the two heels), as well as the female gestational period (260 days, approximately nine months).

Claiming a space of sensorial presence, Chavajay’s new standing sculptures emerge as bodies that share and activate the primordial wisdom of the cosmos, integrating multiple Kuku. These consist of ceramic vessels historically used in indigenous practices associated with the transport of goods, the collection of lake water, and ritualistic and funerary ceremonies, traditionally buried alongside the deceased and believed to materialize the nawal that protected individuals in the afterlife. Revisited by Chavajay and adorned internally with cosmic representations, the pots’ rounded, womb-like forms conceive within their interior the life-generating seed of the world. Arranged upon five wooden structures and wrapped in agave fiber – referencing the tumplines used by Maya communities to carry heavy loads and facilitate land-based trade – the sculptures simultaneously portray a deliberate numerical symbolism aligned with the sacred count of the 13 energies of the Tzolk’in, in which the number 5, understood as the harmonic algorithm, occupies a central position. Signifying balance, the symmetry of human experience (five fingers on each hand, ten in each pair, twenty in total), the stages of life (childhood, youth, adulthood, maturity and old age), and the ordering principle of energetic expansion, its potency arises from a conception in which nothing is arbitrary, and where every sensorial experience contains a reason for being in the intermittent order of planetary existence.

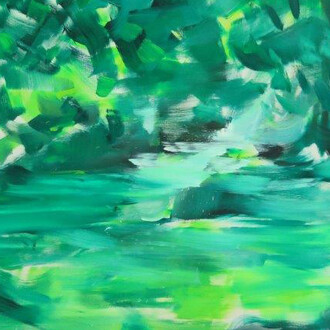

Within this cosmological sensibility, the new paintings occupying the exhibition space likewise configure a scenography that frames the practices of these communities, rooted in the natural environments of Lake Atitlán itself. Belonging to Chavajay’s ongoing series Untitled (hay días que se acercan las montañas y los volcanes), the oil, charcoal, and petroleum paintings on canvas not only articulate a critical inflection on territorial dispute and ecological contamination, incorporating polluting residues produced by tourist boat engines, but also reaffirm the sacredness of the land as a living presence. With a natural horizon marked by the memory of cataclysmic eruptions, these works capture the sensorial perception of a time in constant transformation through phenomenological and atmospheric shifts, registered in the apparent approach or withdrawal of mountains and volcanoes according to cloud movements, time of day, light intensity, or rainfall itself, where the landscape reflects a connection to the vitality of unique and unrepeatable moments.

As a Maya Tz’utujil artist, Chavajay seeks to establish within the space of Rupeequul kaajuleew / Vientre de los cosmos an intrinsic bond with the elements and teachings that compose the universe and the ancestral conceptions of his native territory, calling forth a historical consciousness of indigenous identity and cultural richness grounded in a spiritual and profoundly symbolic order.