A person I deeply respect, Sotiris Botas — unknown to most, although for decades he was the unofficial and extraordinarily prolific secretary of Mikis Theodorakis — called me recently to exchange the customary wishes. He told me that now that words have come to mean nothing, perhaps the time has come — perhaps this is the era — of silence. Of absolute silence, which can signify everything. Silence as a revolutionary act and stance. Silence, catatonic muteness, as an expression of protest and dignity.

I, however, am an incorrigible writer, and so I will resort to words — my only weapon — to speak, paradoxical as it may sound, about silence. And I will speak about silence taking as both point of departure and ontological example the work of Nikos Kaskouras. A body of work that balances, as I have written before, between a most desperate humanism and the most expressive — almost ecstatic — version of visual minimalism. To see through what is either not visible or only faintly appears. Like in a black-and-white dream that has not yet decided whether it is revelation or nightmare.

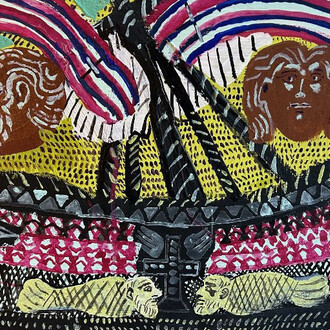

I would say, by way of synecdoche, that in Kaskouras’ painting and sculpture, silence is transformed into images, silence becomes writing in the rhythm of breathing, and silence is transmuted into symbols at once primordial and protean. I would also say that the protagonist of his work — the human figure, genderless and loveless, that is, alienated — having spoken like Kafka or Pollock, and having screamed like Ginsberg or Bacon, has now decided to remain silent. A silence among the whites and greys that recede, the gusts of blue and the flickering of red that slowly fade, and those blacks that came to stay. How else?

Nassos Vagenas writes:

“The air keeps carrying down frozen memories. Let us see what the remainder of Creation has in store for us…”.

The remainder of Creation, then, hovers between the words that were spoken in vain and that silence which remains in order to console and to vindicate human anguish. Shall we call it art? Shall we call it painting?

Kaskouras, through the absolutely consistent evolution of his research, poses the questions himself:

How does one paint emptiness? Or, worse still, the invisible? What kind of images must a painter produce today when from all sides he is being told of the death of painting? How can one balance between what is visually essential and the idealism of the minimal, avoiding clichés, repetitions, and visual boredom? How can the deepest existential drama be rendered in form without resorting to sentimental narrativity? In what ways can iconographic tradition be renewed without falling into easy illustration and even easier decoration?

With his work, the painter proposes meaningful silence. Today. In any case, at the depths even of abstract, “pure” painting, and in the most determined image of the minimal, a story stirs slowly. Let the rest be taken up by the cosmographers of existence and those poets whose verses are destined never to be read by anyone…

Postscript.

I wrote in the past about Nikos’ work. I stand by those words unreservedly in his present, so crucial exhibition. Can painting say anything different today?

“It is to these and many similar questions that Nikos Kaskouras seeks to respond through his painting. A painting that gives substance to the minimal, to gesture, to the primordial, and that appears overall as a persistent exercise in austerity. Its entire thematic field is focused between the figure and space, between a landscape–grid–prison and a fragmented face–mask that could be all of us. The final question: How does one paint fall, fragmentation, disintegration, loss, the degradation of meaning as well as of the image? I honor Nikos Kaskouras’ painting because it is uncompromisingly courageous in a world of the submissive and the merchants, and in an artistic field dominated by mediocrity and ‘professionals’. Kaskouras denounces by remaining silent, by painting, by persisting. An easy academic approach would call his intensely charged, gestural paintings expressionistic. I call them ‘the painting of a desperate humanism.’”