Krakow Witkin Gallery presents an exhibition of works by Julie Mehretu, Sarah Sze, and Jacques Villon. Mehretu and Sze both have active studio practices today, while Villon passed away in 1963. Perhaps an unexpected grouping, the exhibition departs from a thematic or stylistic framework to instead offer viewers the opportunity to engage deeply with three approaches to image-making, mark-making, and composition. Rather than shared history, what brings these pieces into dialogue is each artist’s individual methodology for mapping out and constructing visual space.

Achille (epoch) by Julie Mehretu (b. 1970, Ethiopia) is a nine-color etching with aquatint and spitbite, created in 2015. The title and the medium of this work both point toward the artist’s multi-layered practice. While Mehretu frequently works from photographic source material and uses titles that suggest a situation or narrative, the artist’s imagery is inherently abstract.

In the exhibited work, each layer of printing suggests successive fields of marks, with highly differentiated line qualities, colors, and energies. The marks themselves are the visible actors of the print, yet their relationships map out interstitial spaces that suggest a living, shifting visual landscape where depth seems to exist and yet no definition of that space can be discerned.

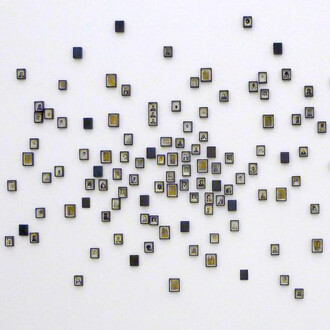

Sarah Sze (b. 1969, Boston) has cultivated a practice that incorporates found objects which have, in her words, “little individual identity” into fragmented, distributed networks of relationships and interconnections, often in the form of immersive, kinetic installations. The exhibited piece, The moon is distant from the sea (2024), embodies a microcosm of Sze’s approach in tracing a connecting line across material and pictorial space.

A white piece of string, attached to and touching the top edge of the paper, descends across the surface of the work, crossing the embossed platemark onto the digital/photographic background element. The string proceeds to descend toward the bottom of the paper. Beginning about a third of the way down, the string seems to have not only a physical shadow, but a digital shadow that originates as part of the background imagery. The string is held in tension by scraps of tape but also interrupted and redirected in places by loops and knots. The direction, orientation, and relationships of planes and objects are intentionally ambiguous, as the viewer can see the string pass both over and under the tape. This blurry field appears to mirror or continue the network of objects on the surface of the paper on and out of view, crossing a secondary picture plane that is internal to the work.

Apart from the string and tape, the only sharply defined element is a torn piece of paper, collaged to the surface, that is printed with an image of a light source in a blue sky. This too is blurry and undefined, except for an optical artifact of lens flare that brings the viewing surface back into focus. The narrative situation of the work is left deliberately undermined, while the title and the journey of the string point the viewer away from distinct, independent objects and toward a web of mutual reflections and interbeing, all of which is consistent with the artist’s continual use and reuse of imagery of her own situations within those situations. Connection, continuity, and delicate balances are key in Sze’s work.

Jacques Villon (1875 Damville, France–1963 Puteaux, France) began his career as commercial illustrator before devoting himself to painting in 1910, around the same time that he established the Puteaux group, a Cubist collective that included Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, Francis Picabia, and Villon’s brother Marcel Duchamp, among others. The tension between representation and pictorial abstraction would continue to be an activating force in Villon’s work throughout his career.

A consummately skilled draughtsman and printmaker, Villon tirelessly studied and experimented with the construction of image space through the articulation of marks. He developed many works through multiple studies and versions that show the outer forms emerging in layers like geological strata. The exhibited engraving, Quartier de bœuf (1941), is an image that has been painstakingly built up through hatching in successive passes and directions, where a full range of tonal values has defined the volumetric space of the eponymous side of beef, but the artist has stopped just short of adding surface detail to clearly denote the subject.

Like the display of butchered meat, Villon has printed his engraving plate with all raw lines fully exposed in their fragility. The ambiguous form has an elegant and yet raw corporality. In some places it suggests a torso, recalling the wartime period in which it was printed. The tones are heavy and solid, while the visible fabric of the linework denotes an incomplete state of becoming and undoing. While unusual to place Villon’s work in this context, the hope is for a renewed interest and exploration into the artist’s devoted, fluid, and yet raw approach to artmaking.