The largest microbial organism in North America is the humongous fungus (Armillaria ostoyae), located in the Malheur National Forest in Oregon. This single organism spreads through a vast underground network of mycelium, covering an estimated 3 1/2 square miles. The discovery of the giant fungus in 1998 heralded a new record holder for the title of the world’s largest known organism. Based on its growth rate, the fungus was estimated to be 2,400 years old but could be as ancient as 8,650 years, which would earn it a place among the oldest living organisms, as well.

By the time of this discovery, Kiki Smith had spent over 15 years exploring the human body in art. Whether individual limbs, organs, liquids, other materials related to the body, interactions thereof, or other related imagery, the artist had successfully shared her vision and thinking with a wide swath of the art-viewing public. Museum exhibitions, awards, and presence in renowned collections the world over established Smith’s fame, but with the above-mentioned discovery, a new chapter began to unfold for the artist as she expanded her practice to include the celebration and exploration of nature.

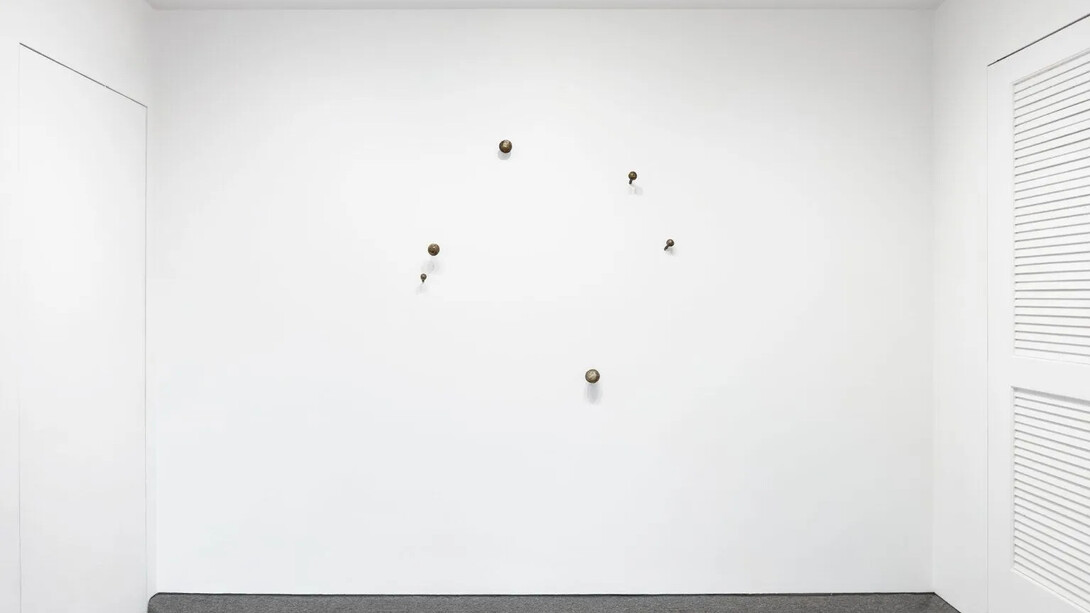

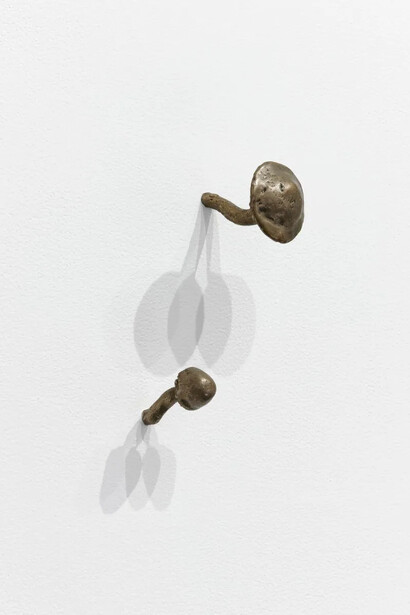

The currently exhibited work, Mushrooms (1999), was among the first sculptures that the artist made following this newfound path of wonder. From a formal perspective, the juxtaposition of the sculptural elements of “Mushrooms,” each individually formed and cast, gives a sense of individuality and yet, by being installed on the smooth uniform plane of a gallery’s wall, nature and human/artifice are conjoined. This is complicated by the mushrooms having been formed by the hands of Smith (visibly so) and yet hinting at the subterranean connections that take the individually visible parts of the fungus and unite them as one large organism. A larger “cousin” of the work, exhibited at Barbara Krakow Gallery in 1999, was then acquired for the Broad collection.