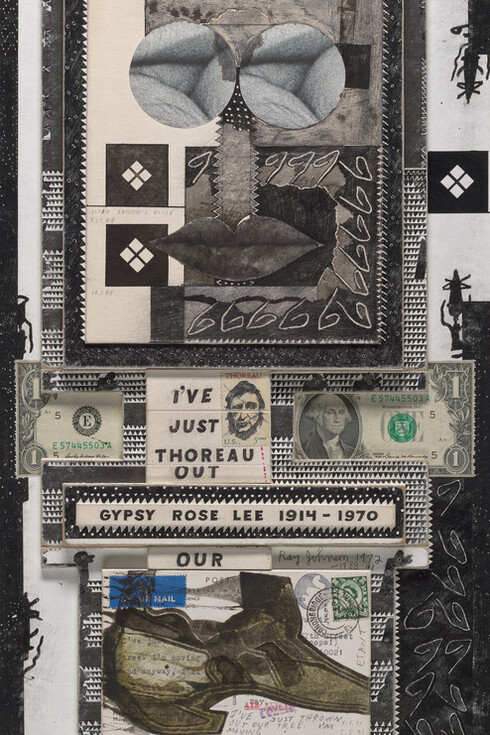

Writing functions not only as language, but also as a visual and even tactile form. Famed artist and educator Josef Albers imparted this idea to his students at Black Mountain College, a former liberal arts school in North Carolina, where artist Ray Johnson studied from 1945 to 1948. In an exercise called “typofacture,” Albers asked students in his design course to create drawings mimicking printed or handwritten text.

After observing textures on surfaces — like speckles on a wall or patterns in a raked garden path — they applied the concept to printed text, which bears the imprint of its production, whether by hand or machine. This activity left a lasting impression on Johnson, a future collage and correspondence artist, whose works (like Paul Klee’s) frequently combine text and representations.

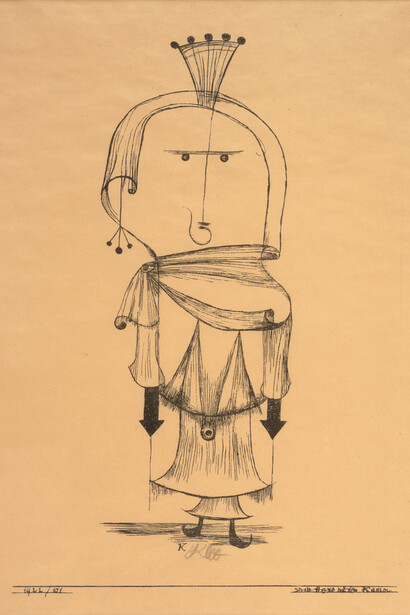

Klee’s merging of myth, symbol, figuration, and expression resonated with many at Black Mountain College and shaped Johnson’s approach. In a 1947 letter to a peer, Johnson enclosed an image of Klee’s Actor’s Mask (1924) with the postscript, “I send a Klee with cracks.” His admiration deepened into a recurring influence, visible in his expressive line work and iconic motifs like arrows and spirals. Whereas Klee’s imagery builds dreamlike worlds, Johnson’s marks accumulate like field notes across a creative terrain.

![Ray Johnson, Untitled [Back of envelope with collage of stamp, letter A, banana and fingerprint] (detail), n.d. Courtesy of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art](http://media.meer.com/attachments/3469de356d015a6fe388ed4dc6f23023e09db5b4/store/fill/690/388/67242474863f256ee637b36267f05119596d93ca1a63de479f980a8edb5d/Ray-Johnson-Untitled-Back-of-envelope-with-collage-of-stamp-letter-A-banana-and-fingerprint.jpg)

![Ray Johnson, Untitled, [Halftone of Elvis Presley's face, smoking pipe added, blocks below], n.d. Courtesy of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art](http://media.meer.com/attachments/43550961878a7403603bebd9da28e0e9b2ded8e3/store/fill/410/615/3812bacbc516200212b056b51d99842bbe27ffcc6ff90489ef4487f2d3b4/Ray-Johnson-Untitled-Halftone-of-Elvis-Presleys-face-smoking-pipe-added-blocks-below-nd-Courtesy.jpg)