Cian Dayrit (b. 1989, Manila, Philippines) uses his first UK solo exhibition to unpack what he calls ‘the infrastructure of corruption for infrastructure corruption’ providing the Philippines as a microcosm example to spell out the mechanics of the Global South as it is today.

Across the tapestries in his exhibition are images from the 1930’s Journal of Public Works, which details infrastructure projects in the Philippines. When we think of roads, dams, energy networks and bridges we think of civilisation not of aggression and this, along with the vast budgets involved, is why they are so ripe for corruption. In these conditions, if you want to extract a wealth of minerals or oil from under a forest, a town or an indigenous community you can build a road through it. You displace a community and break ground without ever needing to commit culpable violence. It is this sort of misuse of infrastructure projects that cloaks a kind of ‘business as usual’ that has only slowed a little since the advent of colonialism. In some cases it has even sped up.

As Dayrit examines in his embroidered annotations, these projects that purport to be for the public good - and which could be in some countries - are often rife with direct fiscal corruption when they use public funds, or are intentionally divisive when backed by corporations and foreign money. They are used to delineate class and race and to shape society, in acts like intentionally placing a new bridge to give certain groups preferential access, while the destruction of another cuts off a community from resources, schooling and prospects.

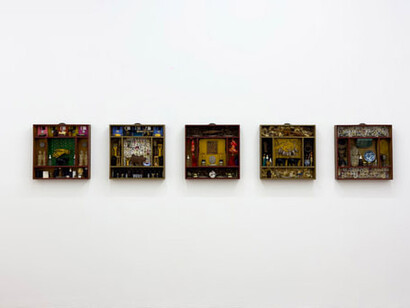

In other sculptural assemblages, assorted objects from the artist’s family’s home, and neighbours are amassed. Material from generations of middle-class Filipino’s, from work related paraphernalia to little tokens sent by family members who have become overseas workers, taking on blue collar jobs in the middle east or US or Europe. An embedded and well-maintained condition of economic disparity for the average Filipino, has been leveraged to the point where many have to leave home to look after foreign families in order to feed their own. Labour is cheap and is kept cheap. It is not just resources but people who are exported here and this is enshrined at a political level in The Philippine Labor Export Policy (LEP), begun in 1974 under Ferdinand Marcos. What underpins this is an import dependent and export-oriented logic where a small top tier of Filipino society, dwarfed by a swathe of foreign beneficiaries, own and export the country dry. In doing so they ensure that they can sell the populace foreign imports at profit and extort and export their labour too. It is not for nothing that one of Dayrit’s recurring motifs is the reference to European Feudal era tapestries. While the ancestors of those who instigated the Feudal System have been unable or unwilling to maintain it, it has been effectively outsourced, offshored and continued.