Derek Eller Gallery is pleased to present a solo exhibition of new paintings by Clare Grill entitled Parlance.

Thick vertical lines hum close to the surface of Flit like folds in a translucent curtain. Toward the top of the painting, a faded orange circle hovers off to the right of a smaller, more emphatic version of the same. A sun and its ghost? A siren and its shadow? Clare Grill’s paintings are, among much else, documents of accretion, profoundly attuned to their own past lives and to the gestures that conveyed the work from there to here. These flickers and remnants of earlier work never disappear into the background—they linger, waiting for Grill to arrange them in pictorial space and activate them in the painting’s hierarchy.

For Grill, the background texture of a painting is as consequential as the marks and shapes that populate the foreground. “I care about the whole thing,” Grill says, down to the edge of the canvas, the corner where its face turns to become its side, which she attends to with her typically unwavering conscientiousness.

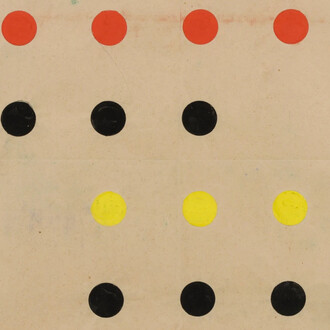

As Grill’s paintings evolve over months and sometimes years, she paints Signets, small works on paper that concentrate the most cherished elements of a work just before it’s transformed and repainted. Once Grill embarks on a new painting, she might return to some of these Signets, treating them as clues or leads—“more bits of information to collaborate with,” as she puts it. In this way, Grill’s artistic process itself becomes a key touchstone for her own work alongside other, more interior forms of inspiration.

The beautiful and disarming paintings in Parlance overflow with surprising juxtapositions of color and texture. They encourage infinite chains of association both stubbornly physical (the background of Flit as mesh or gauze, the possibility of a log and a stump in Lop) and mysterious and ethereal (autumn leaves drifting in a puddle, a sudden vision of the sky in Weld that one might confuse for a hole in the canvas). The surprising use of shadow in Flit calls to mind the blocky lettering on a midcentury movie poster, while the diaphanous simultaneity of shape and background in Dune is so enfolding that it can only refer to an emotion or a mood—to something total and all-consuming.

As pleasurable and open as these paintings are, they’re also dense with private references—words, letters, figures that might be words or letters. What registers at first glance as a constellation of stray components quickly coalesces into a parlance at once intimate and detectable to anyone willing to stop and look. Parlance is full of allusions to Grill’s great-grandmother’s shorthand writing, and to her young daughter’s invented “witch language” and her fake cursive, a pattern that possesses the fluid and halting quality of handwriting but isn’t actually writing—not quite. As with the traces of lettering Grill uncovers in antique embroidery samplers, these subterranean forms of writing exude meaning even as they resist definitive interpretation. Much like abstraction itself.

(Text by Mark Krotov, 2025)