In his sixth solo exhibition at 47 Canal, Trevor Shimizu continues his exploration of painting and artistic personas. Expanding from his landscapes that capture enigmatic seasonality and temporal shifts, this new body of work builds on his formal approach to painting abstraction, bridging connections between facture and the synchronicity of time and movement. The exhibition is accompanied by a related program of video works, curated by Shimizu, in collaboration with the New York–based nonprofit Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI).

Painting primarily from memory, Shimizu’s landscape works exemplify the artist’s dense and energetic style: dry calligraphic marks with layers of paint economically applied. His techniques imbue a complex transparency in the landscapes, allowing the coloration of flora and other seasonal markers to blend together. This new body of abstractions pushes these techniques further, building on his interpretation of historical genres towards themes of transformation and physical process in painting.

Following the arc of his practice, his previous work has always taken the subjectivity of painting as material (vis-à-vis his takes on “painterly personas”). Here, his abstractions frame his interest in the performance of painting through raw physicality and physical intuition. He makes references to artists such as Dan Graham, Paul McCarthy, Bruce Nauman, and Carolee Schneemann, whose performance and video works he came to know closely during his time as technical director at EAI from 2005 to 2013, amongst many other pioneering artists in the collection. Though he was initially drawn to comedic and personality-driven work, his recent reflections regard the artist’s body and movement in tandem with mark-making.

His long-held interest in video art also belies a greater interest in the durational aspect of making art and the ephemerality of life in and of itself. Where his landscapes capture a season already past, indicated in the appearance of spring flowers or autumn leaves and a shift in cool to warm color palette, the formal elements of the genre are stripped down simply to the quality of light in the diptych 2025 light painting (1 and 2) (2025). A sense of time dissolves into a matter of timing in the painting Dahlias and tulips (1) (2025), which depicts flowers with two distinct blooming periods here on the same plane.

In Shimizu’s reorientation toward the canvas, his abstract paintings absorb the artist’s intuitive choreography while likewise running the gamut of modernist visual tropes. Grids dissolve under a thick tangle of charged marks. Faint geometric shapes emerge within a disheveled yet vaguely organized pictorial field. In between layers, the artist tucks familiar subject matter within the seeming thicket of allover painting: portraits of his family’s pets that include a caged hamster and cats named Girl Snow and Olaf; traces of his children’s drawings; underpaintings of colors plucked from strands of a friendship bracelet.

In this mode of self-reflection, Shimizu indexes the quotidian aspects of his own life as domestic scenes are compacted and abstracted for a partial view. After undergoing physical therapy as a result of a sledding accident several years ago, the artist started strengthening and recalibrating his body’s movements—thus changing how his body relates to the canvas and how he moved throughout the studio. To fortify both sides of the body and balance his movements, Shimizu began to paint ambidextrously and approached the painting’s support more methodically. Even still, impressions of the stretcher bars below indicate the force and energy with which he paints.

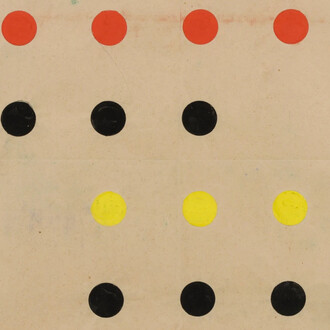

To make these works, Shimizu uses castoff brushes and paints in his studio that are left over from completing previous works, employing—as ever—what is at hand. The artist alternately approaches each canvas affixed to the wall—back and forth, down the line—to apply pigment layer by layer. He builds up the surfaces of his paintings across a series of several sessions. In earlier paintings, Shimizu often limited himself to a three-color palette with minimal brushwork. Here, he reintroduces the same constraint—but only per session, the accumulation resulting in intensely hued and sensuous surfaces that encapsulate a progression of painterly gestures and movement over the course of weeks.

Thus the artist insists that the way he works is not inherently conceptual in approach, but a result of practical and ergonomic decisions. He says, “My approach is irrational and unpredictable, depending on how my body wants to move.” Though minimal in application, the paintings Olaf (Akiva’s version) (2025) and Snowy (Akiva’s version) (2025) took the longest to complete, and lay bare a kind of index of brushstrokes and marks that repeat across them all. Through the physical process of formal repetition, memory, and intuition, Shimizu continues to build upon a layered methodology of his work and practice as an artist.