The founding of the Yan capital began with Taibao, opening the first chapter in its history. After King Wu of the Zhou Dynasty overthrew the Shang regime, the Duke of Shao was enfeoffed in Northern Yan and built the Yan capital in the Liulihe area. This Taibao’s Ramparts at Yan marked the start of Beijing’s city-building and its integration into the governance system of the Central Plains.

As the largest and most extensively excavated Western Zhou feudal state site, Liulihe boasts the richest archaeological finds of its kind. It is listed among China’s “Top 100 Archaeological Discoveries of the Past Century” and the “Top Ten Archaeological Discoveries of 2024.”

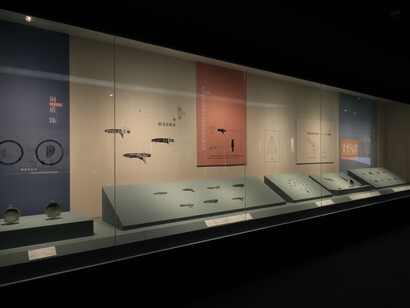

Featuring 180 artifacts, including 113 on first-time display, this exhibition presents treasures that embody the origins of Beijing. We invite visitors to pause at this “origin point” of the city’s long and continuous history, immerse themselves in Fangshan’s enduring story, and draw strength and confidence from its cultural legacy.

Mandate on the northern frontier

The ancestors of the Zhou people trace back to Hou Ji, a legendary figure from the time of Emperors Yao and Shun, who was active on the agriculturally favorable Loess Plateau of Shaanxi. Over 3,000 years ago, Danfu, the grandfather of King Wen of Zhou, led his clan to relocate to the Zhouyuan region at the foot of Mount Qi (present-day Qishan County, Shaanxi). After King Wu of Zhou defeated the Shang Dynasty, he honored the ancient sages by bestowing titles in the region of Ji (modern-day Beijing), and enfeoffed his kinsman, the Duke of Shao, to establish the State of Yan in the Liulihe area of Fangshan. There, the Duke was tasked with pacifying the northern tribal groups and overseeing the remnants of the Shang population—safeguarding the Zhou Dynasty’s northern frontier.

The founding of the Yan capital

The latest archaeological discoveries confirm that the builder of the Yan capital at Liulihe was none other than Taibao, the Duke of Shao himself. Within the site, the nested layout of the inner palace city and the outer city wall, the expansive rammed-earth palace foundations, and the coexistence of diverse residential and functional spaces serve as tangible evidence of the urban planning and organizational structure of a Western Zhou city. These findings reflect early Chinese concepts of capital construction and provide invaluable material proof for the study of ancient urban civilization in China.

Vessels for heaven and Earth

In the Western Zhou period, particular emphasis was placed on ritual sets of food vessels. Among them, the ding (tripods) and li (lobed tripods) were central cooking implements and key components of ritual assemblages, often used in matched sets. According to the hierarchical ritual system, the Son of Heaven was entitled to nine ding, eight gui (food vessels), and eight li; feudal lords were allotted seven ding, six gui, and six li; while high-ranking officials could use five ding, four gui, and four li. The Liulihe site has yielded the largest and heaviest bronze vessel ever discovered in Beijing—the Jin ding—as well as the only known li-shaped bronze vessel of its kind in the country—the Boju li. These remarkable artifacts represent the pinnacle of bronze craftsmanship in the Beijing region. Closely tied to the ritual and musical systems and cultural norms of the Western Zhou period, they serve as enduring and weighty carriers of early Chinese civilization.

The Yan capital at Liulihe was founded in the early Western Zhou period. After the mid to late Western Zhou, the Yan state moved its capital to Ji (present-day Beijing), and the Liulihe capital was gradually abandoned, lying in slumber for over two millennia. It was not until 1945 that the site came to the attention of the archaeological community.

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing Municipality and Fangshan District have actively introduced policies to support archaeological excavation, conservation, and the transmission of heritage at the Liulihe site. In addition to advancing the construction of museums and a national archaeological site park, they have also made significant efforts in areas such as relic restoration, public outreach, community engagement, and international exchange—infusing the cultural heritage of Liulihe with renewed vitality and brilliance.

Epilogue

The Liulihe site is a witness to over three millennia of Beijing’s urban civilization, the historical root of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei integration, and a key example of China’s multi-ethnic unity. It holds outstanding historical, cultural, and social value.

Recent archaeological finds, along with research achievements and texts such as Taibao Yong Yan, affirm Beijing’s continuous urban history since the Western Zhou period, marking its rise from frontier outpost to national capital.

With the World Heritage nomination and National Archaeological Site Park development advancing, Liulihe’s preservation will enter a new stage, further strengthening Beijing’s role as a national cultural center and its “golden name card” of history and culture.