Hegel and Schopenhauer were contemporaries. They remain towering figures in philosophy, but their story also reveals the reality of the academic system, where success often depends less on the strength of an argument than on connections, politics, and zeitgeist. Hegel was the star of his age. Many were fascinated by his sophistication and his vision of human progress. His dialectics and historicism inspired thinkers far beyond his own time. Even today, many philosophers and social scientists still lean on Hegel. Slavoj Žižek, for example, often insists he is more Hegelian than Marxist. And in my view, I understand why. So, let us see who Hegel was.

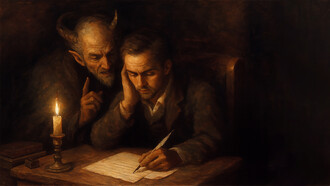

In his later years, Hegel became professor of philosophy in Berlin, under the flag and sponsorship of the Prussian king Frederick William III. His appointment in 1818 required state approval. The king and his ministers wanted the new university to embody Protestant values and state authority. Hegel’s philosophy of the rational state was seen as broadly supportive of monarchy, politically safe enough to be embraced. Many of his admirers prefer to overlook this. After all, how could a philosophy often interpreted as emancipatory also serve as justification for authority?

As a student, I too once saw Hegel as the philosopher of freedom, rationality, and progress. Yet over time, I came to see this as dangerously naive, something Karl Popper explained in The Open Society and Its Enemies. Popper argued that Hegel’s vision risked legitimizing power under the guise of reason.

Looking at today’s world, it is hard not to agree. The dialectical process seems to have glitched. Reason does not govern us. Most ideas never undergo the process of critical thinking. We live in a world that praises “critical thinking,” but often without genuine thought—without the means to achieve synthesis. All that remains is the “critical,” a fitting adjective for our age. Enlightenment ideals of liberty, reason, and compassion are displaced by egocentrism, hedonism, and destructive impulses. This plays out in everyday life as much as in the decisions of political leaders.

So, Hegel’s theory, however attractive, does not hold in the empirical world. It is wishful thinking, even a dangerous fog, disguising the fact that reason rarely drives us. His complexity often shields him from critique—when someone objects, the response is that they did not understand. But perhaps Hegel was deliberately wrong: the great prophet of rational progress gave us a beautiful toy with which to look away from the horrors that reason, in alliance with power, helped produce. Consider the 20th century: World War I, World War II, and the Cold War, or the 21st, with climate crises, wars, and economic instability. Was Hegel wrong, or simply too idealistic? Did his philosophy legitimize what already existed? Nietzsche understood that the greatness of a philosopher lies in seeing beyond the contemporary setting. By that measure, Hegel failed.

One of his contemporaries, however, did succeed even though he was marginalized because of Hegel’s dominance. Arthur Schopenhauer openly despised Hegel. He accused him of obscurantism, of wrapping empty ideas in convoluted language to impress students and please the Prussian state. For Schopenhauer, Hegel’s system was not a path to truth but state-sponsored sophistry. He even scheduled his lectures at the same time as Hegel’s, hoping to compete, but the halls stayed nearly empty. His failure in the lecture hall reminds us: in philosophy, as in science, the better argument does not always win.

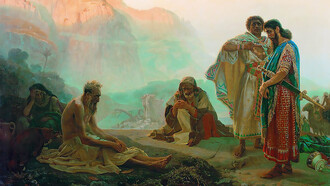

Yet, despite being sidelined, Schopenhauer grasped something essential about both his time and ours. While Hegel praised reason, progress, and the rational state, Schopenhauer insisted that beneath all our ideals (and extending beyond humankind alone) lies a blind, irrational force: the will. He saw that human beings are not governed by reason but by desires, fears, and endless striving that no dialectical system can harmonize. Life, he argued, is a pointless struggle. Reason plays a role, but mostly as a servant of the will.

History has proven him right more often than Hegel. People rarely act out of pure rationality; they bend reason to justify power, desire, or survival. Today, this is even clearer. Our societies are structured by consumerism: endless desire for goods, constant leaps from one object of craving to the next, and the restless search for meaning in commodities. And that is only the personal level. On the global stage, politics is dominated by egomaniacs, not reason. Leaders are driven by inner urges and the will to dominate. Politics becomes an end for itself, a theater of will, not a rational pursuit of the common good. Together, these forces form the basis of a world that manufactures new desires endlessly, pushing us toward self-destruction.

Schopenhauer revealed what Hegel never could: reason is not humanity’s guiding principle. It is an ideal, not a reality. And yet, Schopenhauer did not leave us in despair. He offered ways of loosening the grip of the will.

The first one is art. In aesthetic contemplation, we suspend desire and step outside the restless striving of life. For Schopenhauer, music was the highest art: it expressed the will itself without tying us to any object of desire. For a moment, we stop willing and simply perceive, freed from the tyranny of striving. The second is compassion. By recognizing the suffering of others as akin to our own, we move beyond ego and connect with a shared humanity. Compassion breaks the cycle of isolated desire. And the third is asceticism, the deliberate denial of the will through rejection of worldly attachments. This line of thought (Schopenhauer) influenced some of the greatest thinkers of modernity, like Camus, Sartre, or even Freud.

In contrast, Hegel’s legacy remained the historical hope of a better world, a hope that often proved empty, closer to theology than to philosophy. So, the contrast between Hegel and Schopenhauer teaches a wider lesson. We are often more impressed by idealistic systems than by realistic insights. This tendency persists today, not only in philosophy but also in the sciences, especially the social sciences, where grand narratives and promises of progress still dominate over sober analyses of the forces that truly shape life. Perhaps then it is time we admire figures like Schopenhauer more than Hegel. For Schopenhauer confronted reality directly, without disguise.

At the end, the question remains for the reader: Who is the true Zarathustra—Hegel, the philosopher of progress, or Schopenhauer, the philosopher of reality?