If we pause for a moment to think about the history of numbers, an unquantifiable amount of names from the fields of mathematics, physics, chemistry, astronomy, engineering and cybernetics but also literature, art and music, and even technologies of war or indeed games, come to mind in a flash. In fact, major breakthroughs in the field of mathematics and physics have gone hand-in-hand with sophisticated methods of creating and destroying the world in which we live and, in consequence, have affected the way we tell our stories. Jorge Luis Borges often dealt with such questions in literature.

For instance, in An examination of the work of Herbert Quain, one of his short stories from 1941, the narrator recalled how Quain, a fictitious writer, had said that in a certain novel of his he laid claim “to the essential features of all games: symmetry, arbitrary rules, tedium”. In fact, he called it a “regressive, ramified novel” given that each successive chapter returns to the eve of the event narrated in the opening chapter and ramifies in different versions. And so, it seems as if we are presented with various different curtain-raisers to the opening scene. A thought that reminds us of the theory of possible worlds, multiverses and the game of the universe ad aeternum.

After all, play is a fluctuating balance between strategy, calculating probabilities and, of course, magic. This idea rooted in the Borgian universe of games, riddles, metaphysics and mathematical problems is also a source of inspiration for the three artists whose works are featured in this exhibition. Esther Ferrer, Tom Johnson and Isidoro Valcárcel Medina poetically reveal the secrets of the universe encapsulated in logical structures built on mathematical precepts. An unvarnished world of pure concept. An inquiry into the laws governing the cosmos and the order of our planet through a study and use of numbers, geometric forms and systems of mathematical operations for measuring objects, space and time. In the work of Esther Ferrer (San Sebastián, 1937) we can discern difference produced by repetition. The iteration of prime numbers, a series that runs throughout the various phases of Ferrer’s life-long practice, points to a truth that transcends to the universe, namely, the existence of a structure that extends towards infinity.

That being said, it advances irregularly, given that, in their progression, prime numbers do not follow a logic of closure but rather one of unpredictable openness. In 1996, Ferrer wrote Le poème des nombres premiers, a brief text that describes a series of prime numbers as an internal rhythm of discordant frequencies; here, the dissymmetry within harmony and the chaos within symmetry permute into infinite possibilities. This same idea is then extrapolated to works that are never exhausted. For this reason, in this exhibition we can find works from previous years that stimulate this repetition and difference alongside works from 2025 belonging to the eponymous series: Le poème des nombres premiers.

In it, the artist casts a field of light beams over the prime numbers that reveal differences in reality, planes of iteration, of bonds and misalignments between numbers, the positions that disclose lacunae or gaps in the series. Taken together they build fractal forms predicated on the spiral that Stanisław Marcin Ulam, the Polish-American mathematician in the group directed by Oppenheimer within the Manhattan Project, proposed in hexagonal form. In the ocean of numbers, the artist conceives the universe as an infinity sign. Accordingly, the infinite is a never-ending unpremeditated sequence that becomes a plastic, malleable and virtual code, as if it were a game. In musical compositions, repetition within play takes the form of regulated intervals. The work of the musician and experimental minimalist composer Tom Johnson (Colorado, 1939- Paris, 2024) expands into the realm of conceptualism through the drawings in this exhibition. These drawings, dated between 2007 and 2024, refer to musical compositions where notation is connected to mathematical enunciation. These scores, which is how the drawn figures and numbers should be read, are open to multiple interpretations of an imaginary music at the intersection of music, science and the visual arts. Gilbert Delor defined Johnson’s work as logical music because both the musical composition and the visual work are unfolded as the multiplicity of possible solutions to a problem formulated by Johnson.

In some cases, the notational writing is inspired by the design of blocks from computational logic, like those based on the series of numbers 12, 3, 2 or 11, 4, 6. In the case of Johnson, we might wonder which came first: the composition of the drawing or the acoustic idea? Some of his works are structured through aural drawings that translate music into the form of a score, while others draw earlier sound productions following his own sonic grammar. And in some others, permutations, formulas, fractions and mathematical games give shape to images recognizable as geometric figures, flowers, grids of numbers or stars.

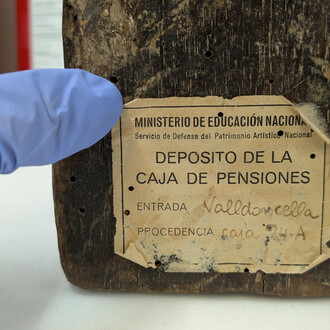

In her series of prime numbers Esther Ferrer looked for a way of abandoning the subjective point of view, while illustrious personalities like Lewis Carroll, especially in his published works on mathematical logic, sought to challenge the cold objectivity of mathematics with emotional and sensitive adjectives and metaphorical representations. Perhaps, halfway between the two, Johnson evokes things submerged in an ocean of chords coming from somewhere between combinatorics and nature As the saying goes, the devil is in the details. Lewis Carroll and Martin Gardner in his Mathematical Carnival proposed a science steeped in the logic of games, astuteness, seduction and a certain digression. Gardner reminds us of the importance of knowing geometry in order to outwit the devil as Goethe’s Faust did by drawing a pentagram to trap Mephistopheles in his study. In his works Las 3 dimensiones (1996), Teorema (2005) and Untitled (Las 3 dimensiones y Teorema) (1996-2025 and 2005-2021), Isidoro Valcárcel Medina (Murcia, 1937) presents us with a fabulous mathematics, a fantasizing logic, for while the statements and formulations, the mathematical problems and definitions of objects are scientifically rigorous, his way of interpreting or creating connections between them is disparate. The first two of the aforementioned works are unpublished books registered in intellectual property as scientific works under the name Valcárcel Medina. They are full of mathematical reflections that incorporate a narrative running parallel to the scientific viewpoint. Then they become a kind of exercise in erudition, like Flaubert’s Bouvard et Pécuchet, whose meaning is subordinated to playing with the reader as they strive to solve the riddles.

Las 3 dimensiones alludes to the three dimensions of length, width and height: the three ways of measuring objects in the physical realm where we perceive spatial reality, but this time within an imaginary space. In fact, this is one of Valcárcel Medina’s core themes: the relationship with space and, in consequence, with time. Teorema revolves around Fermat’s theorem and presents the most important figures, expressions and problems in the history of mathematics in such a way that they respond to each other with a touch of irreverence and ambiguity. How ironic then, in Fredric Brown’s short story, to see that the hexagram is useless in keeping the devil at bay. Isidoro Valcárcel Medina turns mathematics into reflection, play and artistic practice.

(Text by Johanna Caplliure)