How do geographical conditions affect the migration of artists during the Renaissance?

Frommel: While the Alps formed a definite line of division, the situation was quite different in the case of the opposite banks of the sea, the western and eastern shores of the Adriatic, where an intense interchange of forms and techniques had developed, strongly influenced by Venice. An itinerant figure such as the Dalmatian architect and sculptor Giorgio di Matteo connected the traditions and tastes of both, as shown in the Šibenik Cathedral, an emblematic example of cultural crossover.

It is well known that Renaissance artists competed for commissions, recognition, and patronage of wealthy families. Why was this important? Can you elaborate and give examples?

Frommel: A lively competition involved the most important European rulers, who aimed to adapt local traditions to the most spectacular Italian models to establish meaningful iconographical strategies of self-aggrandizement. Political missions of princes, accompanied by the most important figures of the court, secretaries, ministers, and noblemen, such as the imperial crowning of Charles V in Bologna in 1530, were fruitful opportunities to develop knowledge of the most advanced innovations and ideas, while also communicating with patrons and artists.

As the saying goes: The prophet counts for nothing in his own country. While Leonardo had to renounce a solid position under Leo X, conversely, at the French court, he was appointed “painter and architect,” highly paid, and completely free to do his own investigations. Artists communicate through drawings, but the language problem often proves to be an obstacle. At Amboise, Leonardo was able to join a colony of Italians that had preserved their lifestyle and culinary tradition. Italians were accustomed to a direct and rather personal dialogue with their patrons, but Francis I was surrounded by administrators who made life difficult for foreigners, as Benvenuto Cellini and Sebastiano Serlio complained. This would change after the tragic death of Henry II in 1559, when his widow, Catherine de Medici, strongly reinforced Italian culture and tradition.

Art and architecture were instrumental in spreading new idioms of self-representation, both in the ecclesiastical and princely domains, and this was possible due to the migration of artists.

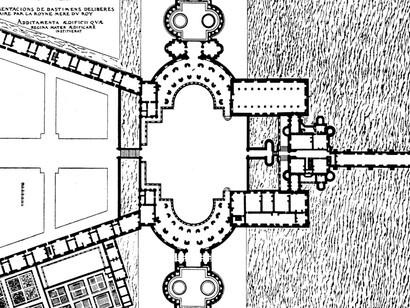

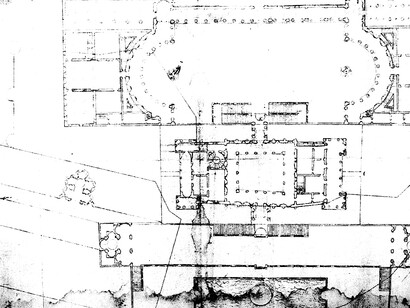

Frommel: Conscious of the power of art, mainly architecture, as a political tool with strong rhetorical value for conveying prestige and legitimization, Catherine played a decisive role in promoting architectural renewal, combining Italian models with French taste. In projects for residential buildings, she competed with Eleonora de Toledo, the wife of Cosimo I de’ Medici, Duke of Florence, as well as Margaret of Austria, Charles V's natural daughter, and also her sister-in-law, Marguerite de Navarre, the Duchess of Savoy. This affirms the decisive role played by female patrons in the history of architecture of the European Renaissance.

The challenges facing Italian artists depended on the genre, and in the field of painting and decoration, they were able to act freely, while in architecture, the building guilds, whose task it was to preserve traditional techniques, abated and even blocked progress. At the court of Francis I, painters and designers like Rosso Fiorentino or Francesco Primaticcio received honors and were richly rewarded, while an architect and theorist like Sebastiano Serlio remained isolated and disappointed. His formation in Bologna allowed him to develop taxonomic research and to continue his ambitious treatise concerning a critical adoption of the rules of Vitruvius and a first-hand discussion of how to connect Italian principles and French domestic comfort. Solidarity seems to have united artists from the same origins, while national pride heightened tension when Benvenuto Cellini joined the court at Fontainebleau, having extolled the superiority of his Tuscan culture.

How was the migration of Italian artists and foreign artists in Italy?

Frommel: Not all the Italians displayed the same adaptability, and the backdrop of the migration process is highly varied. While Florentine artists were supported by a network of powerful figures in the world of finance directly linked to the court, artists from Bologna did not enjoy these benefits, though they were recommended due to their expansive mentality and efficient methods as taught by the Alma Mater Studiorum. They succeeded in convincing illustrious patrons all over the world.

In 1475, the architect and engineer Aristotele Fioravanti arrived in Moscow, where Ivan III commissioned him to create the Dormition Cathedral of the Kremlin, a masterpiece that combined local and Quattrocento traditions, celebrated by believers for its wide proportions and overwhelming abundance of light. It seems that Tuscan artists were more rigorous in their artistic credo, while the courteous and accommodating temperament of the Bolognese master Primaticcio ensured a four-decade-long engagement and a powerful status under the French kings until his death in 1570.

Seen as a whole, conditions of Italian artists in foreign countries were complex and depended more specifically on their age, temperament, and family situation. They had to reckon with prejudice, animosity, and nationalist sentiments, which proved challenging at times. Sometimes, they may have poured oil on the fire, declaring value judgments on the work of local masters, which resulted in anger. On the other hand, artists who returned to their countries after having experiences in Italy were usually celebrated and highly rewarded with prestige.

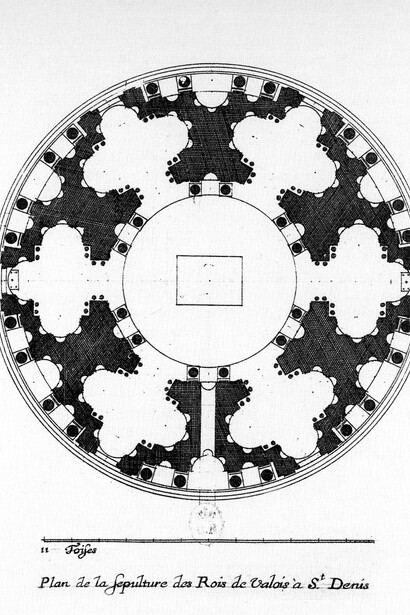

Charles V commissioned not only a sumptuous palace in Granada but also a new project for a cathedral with a funerary chapel inspired by the Roman Pantheon. The architect Diego Siloé was particularly skilled in the process of hybridization because, apart from the Gothic tradition, a significant reference was the persistent assertion of Muslim architectural heritage. In Andalusia, Catholic kings commissioned Muslim craftsmen for works during the conversion of mosques to churches.