Strip to the bones establishes a dialogue between Barbara Hammer’s cinematic work Sanctus (1990) and a new series of abstract paintings on nailed paper and canvas by Margaux Meyer.

Both artists reject classical forms of representation and break with a certain aesthetic tradition, where experimental cinema replaces genre cinema, and abstraction supplants figuration. Their thinking is shaped by reactions and sensations that place the body at the center of their work. Their practices are articulated through phenomenological elements—sensitive and gestural—resulting in a strong organic, then erotic, tension that allows the represented subjects to exist freely. Meyer’s painting breaks away from the physical laws that constrain the body in its representation, manifesting as the distension of cellular tissues, which seem to stretch to the point of rupture, to the point of ecstasy.

Composed from animated 70–35 mm X-rays borrowed from Dr. James Sibley Watson, Sanctus reveals all the subtlety and sensitivity of experimental cinema. By running the photographs through a 16 mm optical printer, Hammer achieves a shifting effect she calls a “color halo”, which she uses alongside her primary colors. Just as Meyer builds up layers only to subtract matter, Hammer reduces images, overlays them, and experiments with superimpositions and collaged negatives until she obtains contrasting halos1.

While Meyer depicts the fragility of organic and cellular systems, and Hammer preserves them by limiting herself to a “skeletal” representation, both artists nevertheless introduce the idea of fatality. Sixteen years after the making of Sanctus, Hammer was diagnosed with incurable ovarian cancer, raising questions about the harmful effects of radioactive imaging. Meyer’s paintings display bodies in perpetual mutation, inevitably evoking natural and biological cycles. The Pelvis series (nos. 30, 41, 33, 27, 52, Girl) conveys this (de)gradation through different states of the subject matter: while some papers perspire successive layers of oil, others are essentially carbonic (Girl).

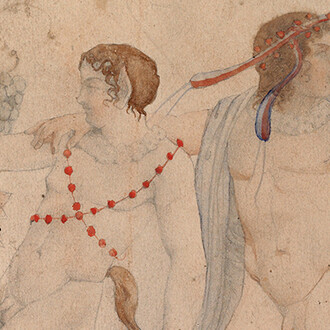

The exhibition thus introduces the image of the “carrion-body”, where the organic decays and only the carcass remains. Entitled Sanctus, the film evokes the duality between science and religion. For the medical field, sanctus means “in good health”, recalling the adage Mens sana in corpore sano. In the Book of revelation, however, it becomes a call to prayer to the Lord Sabaoth, the celestial god of the night. This religious reference resonates with the analog score created by Neil Rolnick, which brings together the Sanctus section of five different composers. Like a danse macabre, skeletons move to the rhythm of experimental prayers. This mesmerizing and erotic choreography continues in Tarp, a work inspired by Holbein’s death’s apparitions (1785)2, where a skeleton, a funereal emissary, captures two lovers in an embrace with the sweep of a sheet.

In Puce moment (1949), Kenneth Anger reclaims the glamorous cult of the Roaring Twenties actress, a social fetish, staging an endless ballet of draperies pulling one another away. Playing on the notion of “striptease”, “Strip to the bones” breaks free from the traditional social codes that sexualize the body. Here, the dialogue emphasizes the internal perceptive phenomena of the female body—such as menstrual fluids, mucous membranes—and underscores their emancipatory functions against the fantasy-images imposed by patriarchal societies.

In her book On female body experience, Iris Marion Young argues that the subject frees itself from masculine alienation by reclaiming personal bodily experience. For Margaux Meyer and I. M. Young alike, this emancipation originates in the womb, as a sensitive epicenter.

The sensation of color resides in the womb.

(M. Meyer)

(Text by Clément Caballero)

Notes

1 DocFilm forum: Barbara Hammer & Cheryl Dunye, DocFilm Institute, 2017.

2 Johann Rudolf Schellenberg, Gestöhrte Liebe. Der Tod bedekt zwey Liebende mit einem Nez., in Freund Heins Erscheinungen in Holbeins Manier, 1785.