Located on the eastern edge of Turkey’s Black Sea region, the district of Rize, Fındıklı, is a landscape where countless shades of green meet the shifting blues of the sea. This rich environment hosts diverse vegetation and a remarkable range of animal species. Growing up, I often listened to my father’s stories about the large, untamed streams that once ran through the villages. In those times, he said, children would catch fish with their bare hands because the waters teemed with life. Among these fish, one species was treasured above all: the Black Sea trout (Salmo rizeensis), locally known as Karadeniz kırmızı benekli alabalığı.

Their name, derived from the distinctive speckles and markings on their bodies1, has long been part of the region’s folklore. With their striking reddish hues glinting beneath the water’s surface, they were once as precious to the ecosystem as diamonds are to the earth. Yet, as population growth accelerated and technology advanced, the delicate equilibrium between humans and their environment began to unravel.

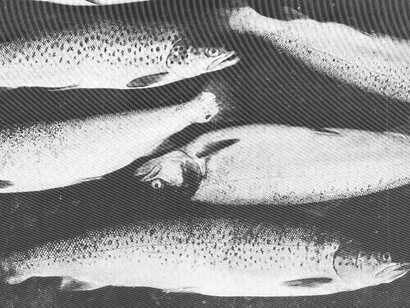

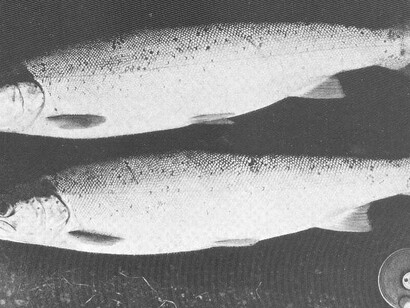

The Black Sea trout (Karadeniz dere alabalığı) is a species highly sensitive to its ecological context, as is the case with most freshwater trout. Their bodies are spindle-shaped, slightly compressed from the sides, and adorned with red spots along their flanks and dorsal region. The back often displays shades of light brown, gradually becoming paler toward the lateral line, while their belly takes on a yellowish-white tone. A distinctive large black spot on the operculum sets them apart. Their fins, brownish-orange with red speckles, add to their singular beauty. Individuals can reach up to 40 cm in length and weigh as much as 3 kg.2

Warming waters caused by climate change, construction along rivers and streams, sewage pollution, and destructive fishing practices have all contributed to the decline of these trout1, turning them into markers of a disrupted ecology. Their fragile state of existence reflects the wider imbalance between human activity and the nonhuman world, and it opens a deeper philosophical question: how do human beings position themselves in relation to the very ecosystems they continue to strain?

Human beings have often placed themselves outside the realm of nature, embracing what is known as “human exceptionalism”. Yet, as Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova argue, humans are inescapably animal, subject to the same cycles of birth, respiration, nourishment, reproduction, and mortality as any other species. The epoch of human-driven environmental change, aptly termed the Anthropocene, is marked by the gradual extinction of countless living entities.3

The strugglefor survival faced by the Black Sea trout exemplifies this dynamic, becoming a site where posthumanist ethics must grapple with its own commitments. Posthumanism, rejecting anthropocentric thinking, advocates for recognising the autonomy and ethical significance not only of animals but also of ecosystems and even technological assemblages.4 This recognition invites a more entangled and less hierarchical understanding of life, where human and nonhuman actors, such as rivers, fish, forests, or machines, coconstitute the conditions of existence.

However, as the Anthropocene unfolds and we integrate technology ever more deeply into our lives, the consequences of this integration ripple far beyond human convenience. Technologies often reframe animals as exploitable resources, farmable commodities, or mere aesthetic artefacts, while at the same time diminishing their recognition as autonomous, sentient beings entitled to coexist alongside us. This dynamic is well described in technological mediation theory5, which argues that technologies not only act upon the world but actively shape how humans perceive and engage with it (Verbeek 2006, 2011, 2016). By ‘amplifying’ or ‘reducing’ particular traits, they influence whether animals are seen primarily as living beings with intrinsic value or as units of production; and by ‘inviting’ or ‘inhibiting’ certain actions, they co-direct human practices toward or away from care, exploitation, or neglect.

Building on post-phenomenology (Ihde 1990, 2009), this view highlights how technologies shape our experience of the world: they affect what we notice, how we understand it, and what we decide to do as a result. In animal agriculture, for instance, milking robots, ‘smart’ monitoring systems, and genomic selection techniques do not merely serve as tools but actively reconfigure how animals are perceived, transforming them into measurable, manageable data points rather than sentient beings.

In the case of the Black Sea trout (Salmo rizeensis), a similar technological mediation unfolds; intensive aquaculture pools established along the coast represent the trout as an extractable, controllable resource rather than as a migratory species integral to the region’s freshwater ecosystems. These pools introduce contaminants, alter marine biodiversity, and disrupt the trout’s natural migration routes. Typically, at four to five years of age, these fish leave the sea to swim upstream and deposit their eggs in sandy, gravelly beds near freshwater2 sources, but this ancient rhythm is increasingly interrupted—compounded by destructive fishing practices, polluted streams, and habitat degradation.

Local accounts further suggest that these practices have more subtle yet profound consequences. As a fisherman friend once shared, trout raised in artificial or hybrid breeding conditions often lose their characteristic red spots because they require high levels of oxygen to sustain healthy development, something rarely achievable when thousands are confined in closed systems.

Moreover, aquaculture cages sometimes rupture during floods or coastal disturbances, releasing artificially bred fish into the sea or rivers, where they mix with wild populations and threaten their genetic integrity. The situation is compounded by the large-scale farming of non-native species such as salmon in the Black Sea, in dams, or in rivers, primarily for export, further straining local ecosystems. While these observations reflect valuable local knowledge, they also highlight an urgent need for scientific research to better understand these impacts and to develop sustainable practices that protect native species rather than endanger them.

This tension between human technological progress and the fragility of nonhuman life forms a critical point of reflection in posthumanist ethics; it challenges us to reconsider whether “advancement” should be measured solely by the convenience it brings to humans or also by the continuance and flourishing of the ecosystems we are entangled with. Such a question does not remain within the realm of posthumanism alone. It also points toward transhumanist debates, where the goal of surpassing human biological limits often clashes with the harm these technologies can cause to the natural world.

The concept of “fish produced in unnatural environments but presented as 'natural'” exemplifies one of the transhumanist markers of the postnatural era. Humans increasingly begin to redesign not only their own bodies but also the broader natural world. Although the intentions of transhumanist interventions may often aim to benefit humanity, their consequences are not always favourable for other living beings. For instance, the Black Sea trout (Salmo rizeensis) has been subject to genetic manipulation. Practices such as hybrid breeding and aquaculture in non-riverine environments pose significant risks to the species’ natural gene pool, threatening the ecological integrity of its populations.

Examining the Black Sea trout (Salmo rizeensis) through posthumanist and transhumanist lenses allows us to reflect deeply on the ethical and ecological entanglements between humans, technology, and nonhuman life. The trout’s existence embodies both the intrinsic value of nonhuman beings, which posthumanism urges us to recognise, and the transformative power of human intervention, as highlighted in transhumanist approaches. Its declining populations remind us that technological and environmental interventions, even when well-intentioned, can have irreversible consequences for the living world.

On a personal level, thinking of the trout brings back my father’s stories of catching them with his bare hands in the streams of Rize—a memory of abundance, wonder, and a life in rhythm with nature. Preserving this species is not merely about conservation; it is about honouring a shared history, respecting the autonomy of nonhuman life, and questioning how we, as humans, choose to shape the world we inhabit alongside other beings. Protecting the Black Sea trout becomes, in essence, a call to act with care, humility, and responsibility in a post- and transhuman era.

References

1 “Rize’de Nesli Tükenme Tehlikesi Ile Karşı Karşıya.” Rizenin Sesi, 2 Dec. 2022.

2 “Kirmizi Benekli̇ Alabalik.” Van İl Tarım ve Orman Müdürlüğü.

3 Braidotti, Rosi, and Maria Hlavajova. “Animal.” Posthuman Glossary, Bloomsbury, 2018, pp. 35–36.

4 Heise, Ursula K. “Chapter 9: Environmentalisms and Posthumanisms.” The Blooksbury handbook of Posthumanism, Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 435–436.

5 Kramer, Koen, and Meijboom, Franck L. B. How Do Technologies Affect How We See and Treat Animals? Extending Technological Mediation Theory to Human-Animal Relations. 2022.