The only thing we learn from history is no one learns from history.

(Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel)

After living in Africa for a year doing research for business intelligence platforms, all I hear sounds like more of the same. Media, events, interviews, businessmen, officials, all repeat the same messages for each sector.

Minerals are the wealth of Africa, fair. Energy: a green future is possible by African rivers and land for solar panels. Digitalization: the young demographics have great potential. Banking: expanding financial inclusion to access untapped reserves of profit (yeah, right). Agriculture: Africa will feed the world, it can barely feed itself. Logistics: the great challenge of Africa. Also, an impossibly profitable opportunity for whoever manages to connect Africa’s vast territory, comprising difficult ecosystems such as savannahs, jungles, rivers, lakes, and a massive desert.

To be honest, there is a lot of truth in this, but infrastructure, security issues, and trade regulations make it the hardest continent for imports-exports and shippings. Logistics, in case you forgot about the pandemic, are the backbone of industry. Interrupt supply lines and you will have empty shelves, simple as.

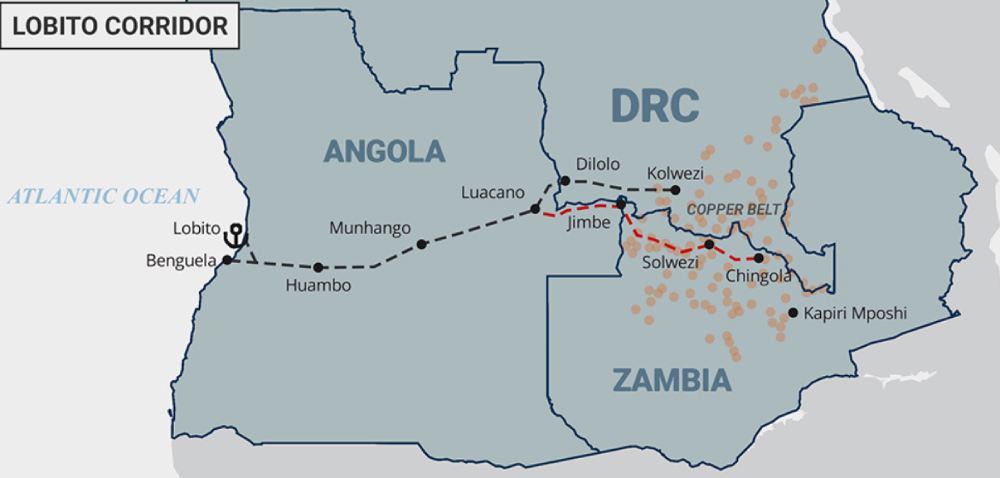

A major talking point thrown around in sub-Saharan Africa when talking logistics is the term “Lobito Corridor”. Essentially, a network of physical infrastructures, mostly railways but also highways and bridges, that will go through Zambia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and into the port of Lobito in Angola. The idea is connecting the mineral-rich “copper belt” of Zambia and the DRC from deep in the heart of Africa with a suitable launching pad for exports in the Atlantic Ocean.

Nothing crazy, sounds logical. It sounds so logical, I wondered why this hadn’t been done before. A Google search shows that for over 10 years, deals, grants, concessions, loans, investments, and other financial terms have made headlines referring to the Lobito Corridor. Massive increase in exports, raw material transformation, agribusiness opportunities, and overall wealth creation in this overall poor continent are all parts of the promises.

Optimistic projections involving “strategic objectives”, “sustainable development”, “key initiatives”, and other buzzwords have failed to deliver. Crazy enough, it has been done before -and better.

Recycling an old idea

In the history of Africa, which I have of course obsessively read since moving here, there are a couple of topics considered no-nos. The bloodiest regimes, like those of Idi Amin in Uganda or the Derg in Ethiopia, are prime examples of what not to talk about at the dinner table. Of course, European colonialism as a whole is a no-no. Unless in London or Paris, since it is eternally in vogue to blame England and France for everything while living in London or Paris. All of the aid money that has somehow aided no one funneled into Africa by development agencies and the UN is another no-no. Ah, wait, I cannot say anything negative about them; they are the good guys of the narrative. And finally, one thorny topic that people decide to skip is Rhodesia, the baddest bad boys to ever bad.

Rhodesia was formally an apartheid (big no-no) state in the most Boer-Afrikaner sense of the word. A white minority exercised undisputed political power and dominated the commercial and industrial circles of this commonwealth country. In the 1960s, at the height of decolonization, England refused to grant it independence unless majority rule was guaranteed. The unmovable stance of either led the Rhodesian government in 1965 to enact a unilateral declaration of independence. Rhodesia became a rogue country, largely unrecognized and pressured by international sanctions.

The few countries that recognized the rebel regime included its apartheid big brother, South Africa, and Portugal. The latter of which was key since it was resisting the wave of decolonization and clinging to its African possessions. These included Angola and Mozambique, which were promptly located to either side of Rhodesia. In the effort to dodge sanctions, having the allied Portuguese regime as neighbors guaranteed supply lines and the shipping of exports. The Beira corridor through Mozambique provided a gateway to the Indian Ocean, while the Atlantic Ocean was reached through the now “novel” idea Lobito Corridor.

Yes, the damn thing already existed. It was tried, it worked. It was even complemented on the other side and crossed Africa horizontally. When the Carnation Revolution overthrew the Portuguese regime, the new government quickly granted independence to its overseas territories, and Rhodesia’s last standing ally was South Africa. This made logistics much more difficult and imports much more expensive. The impossible economic situation and a subversive guerrilla war heavily debilitated Rhodesia. It finally collapsed in 1979 and became what we now call Zimbabwe. Besides its racial policies, Rhodesia is only remembered now for a breed of huge dogs with an interesting fur pattern.

What happened to the first Lobito Corridor?

The original corridor was a train line operated by the Portuguese railway company “Empresa do Caminho de Ferro de Benguela” since 1902. The “Benguela” company had a concession of 99 years (leave it to history books to have the craziest contract terms). Angolan and Mozambican independence was fifty years ago in 1975. Fifty years, of which an astounding 27 were spent in civil war. The civil war ended in 2002, a year after the concession was due, and by then, only 3% percent of its infrastructure was operational.

What has taken them so long to lay track? Ever since, a spiral of mismanagement has caused delays and scandals at different levels. An OPEC member, Angola has used its oil riches to rebuild its war-torn infrastructure, and in 2014, the first rehabilitation process was completed by a Chinese engineering firm. This started a wave of more firms of rival superpowers and trading blocs bidding for contracts. This “hot stuff” element to infrastructure works has created corruption, kickback schemes, diplomatic, shady deals. Essentially, the standard African package is holding back all forms of development on the continent. Nada de novo debaixo do sol. As of now, the woes continue. Mismanagement and competition between Chinese and Western-aligned investment asymptotically compete. The necessary stability for the Lobito Corridor to thrive will remain elusive. Only, the short-lived Rhodesia seems to have made the best out of this trade route.

As a final note, I would like to bring up something I have not yet understood. I have thought about it from every angle and it still makes no sense. Why would Zambia and the DRC like to ship out of the Atlantic via Angola?

China has stepped in to fill the void left by the Soviet Union in Africa. Many of the newly independent countries after decolonization aligned with the Soviet Union. They received aid, weapons, and technical assistance during the Cold War. Now it is the Chinese using debt-trap diplomacy that controls entire countries. The business scenes and trade policies of Africa are pro-China, even for countries that were not aligned with the international left, like the DRC. So why orient all supply chains towards the Atlantic when the biggest consumer markets, industrial transformers, and trade partners are reachable through the Indian Ocean? Reaching China, India, and Southeast Asia through the Atlantic is unnecessarily expensive through the Atlantic. Logistics are faster and cheaper via the Indian Ocean and through the Beira corridor. Perhaps, there is something tasty quietly cooking in Mozambique.