Not this thing or this other thing, but a subject that can stand in for all possible subjects, or, to the contrary, anything placed on the plane.

(Giulio Paolini)

Giulio Paolini (b. 1940, Genoa) engages the vocabulary of artmaking to explore limitless fields of possibility. The works presented in Krakow Witkin Gallery’s exhibition utilize image, language, and physical materials, all aspects of his practice that have evolved continually since 1960.

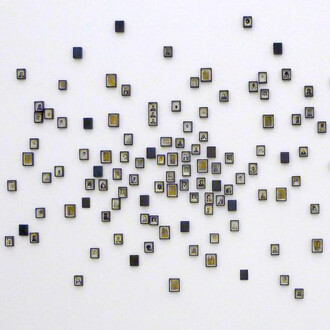

Paolini began making The encyclopaedia britannica (Fourteenth edition, Vol. 12) in 1971 and continues it to the present. The works’ physical forms are that of lithographs identically reproducing a section of the entry for “infinity,” from the Encyclopaedia Britannica. The artist’s use of the encyclopedia’s entry (as opposed to giving a dictionary’s simple definition, thus providing a more extensive meaning for the subject) points towards his interest in exploration as opposed to definitive understanding.

Paolini’s development of the work over the last four decades accentuates an intentional tension between permanence and change. The artist first signed an impression of the print in 1971 and dated it as such; since that time, he has periodically signed additional impressions, co-dating them 1971 and the year of signing. Each piece is numbered, beginning with impression number 1 in 1971, with that number being written with the format of an edition, but with Paolini considering the edition to be of infinity (each piece is numbered X/∞). As the works are partially made over time, while the image of the text never changes, they physically have lived different lives, a fact that is made visible through variations in printing and aging. With this practice, Paolini simultaneously remakes the work, makes new works, and continues an ongoing project and thus investigates the experience, idea, and understanding of infinity through a scenario where the seriality of printmaking exists in tension with the ever-changing nature of ideas and language.

Nove particolari in due tempi (Nine details in two stages) (1984) is composed of nine unbound double-page spreads arranged along the perspective lines projected from a figure (reproduced from Abraham Bosse’s 1648 treatise on perspective) on the sheet placed to on the right-hand edge (not the center) of the composition. The perspectival lines originate, not from the right (writing/drawing) hand of the figure, which is sourced separately from Diderot’s 1763 Encyclopédie, but from its left where it is posed in the act of observing a scene using a string apparatus. As in the Britannica edition, this figure and its sources function as location- and time-stamped counterpoints to the larger work.

In the overall composition, Paolini balances between unifying and dispersing forces and repeatedly upends the hierarchy between artist, viewer, subject matter, source material and end-result. The engraved lines of the figure are contrasted by the rigidly clean and geometric rectangles on the eight other sheets of paper as well as by the straight but hand-drawn lines that unify the overall composition. In addition, the images of what can be read as clouds or the sea are also, visibly, grainy reproductions, multiple steps removed from their sources. Each of these fragmentary images is labeled with one letter of “Mnemosine,” the Italian spelling of Mnemosyne, goddess of memory and mother of the nine Muses. Paolini’s use of reference expands the meaning of the work and serves to acknowledge and focus on the idea of “reference” as a forever-shifting aspect of life. Order (perspective, recursive composition) and chaos (the seemingly haphazard placement of the sheets), the past and the present, the actual and the reproduced—these are all subjects within Nove particolari in due tempi (Nine details in two stages).

In the photographic assemblage Solitaire (2004), Paolini constructs a quieter, introspective scenario of questioning. Encased at the center of a plexiglass box, a photograph shows the artist’s right hand holding a sheet of blank paper. The center of the print, including a section of the artist’s thumb, is cut away to form a rectangular aperture through which another, apparently blank, rectangular sheet protrudes. This sheet is in fact a reversed piece of another section of the photograph, which the missing central piece and several others are scattered at random, throughout the display box. In Paolini’s own words: “The presence of the hand, the sheets that are still blank: this is the itinerary that reveals all that will make up the work, that is, its own path before reaching its fulfillment. The path of the hand without the work knowing.”

Giulio Paolini has had numerous exhibitions in art galleries and museums around the world. Among the largest are those that have been held at Palazzo della Pilotta in Parma (1976); Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1980); Nouveau Musée in Villeurbanne (1984); Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart (1986); Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome (1988); Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz (1998); GAM Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin (1999); Fondazione Prada in Milan (2003); Kunstmuseum in Winterthur (2005); Macro Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Roma (2013); Whitechapel Gallery, London (2014); and Castello di Rivoli -Museo d’Arte contemporanea (2020), Turin. Paolini has participated four times in Documenta in Kassel (1972, 1977, 1982, 1992) and ten times at the Venice Biennale (1970, 1976, 1978, 1980, 1984, 1986, 1993, 1995, 1997, 2013).

The attention is analytical, but the result is enigmatic.

(Giulio Paolini)