Organized in collaboration with the Comité Picabia, and co-curated by its President, Beverley Calté, with art historian Arnauld Pierre, Francis Picabia. Eternal beginning is the first major exhibition to focus on the compelling final years of the French avant-garde artist’s prolific career.

Traveling to New York from Hauser & Wirth Paris, this presentation features over 20 paintings created by Picabia between 1945—when he returned to Paris from the South of France—and 1952, the penultimate year of his life. Representative of Picabia’s restless artistic spirit, the works on view highlight his singular approach to abstraction, his iconoclastic tendency to repaint earlier works and his enduring attention to both surface texture and novel sources of inspiration.

The first 30 years of Picabia’s practice were defined by his rapid progression through different styles and techniques, and his experimentation with a succession of artistic movements that included impressionism, fauvism, dadaism and cubism. In 1925, Picabia retreated from Paris to Mougins on the Côte d’Azur, where he produced his Transparencies—beguiling compositions that layer motifs from ancient artworks and old master paintings—as well as more realistic works, such as landscapes. His infamous naturalistic nudes followed; lurid depictions of female figures excerpted from mass-produced erotica.

In 1945, facing challenging economic circumstances and seeking a fresh start, Picabia returned to Paris. There, he announced in an interview that he was searching for a ‘third path’ forward between surrealism and abstraction, the two dominant forces in postwar European art. Even as he rejected surrealism’s emphasis on elaborate figuration, Picabia aspired to continue—through abstraction—the movement’s engagement with the artist’s unconscious and innermost sensibilities. While Picabia resisted being confined to group labels throughout his life, he was willingly associated with the growing art informel movement during this time, and opened his studio ‘almost every Sunday’ to younger artists such as Henri Goetz, Christine Boumeester, Raoul Ubac, Jean-Michel Atlan and Georges Mathieu.

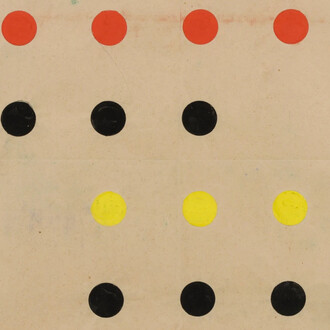

By merging discrete references and artistic traditions, Picabia developed visual and symbolic languages that were entirely novel. Art historians have directly attributed motifs in Le U (1950), Villejuif [I] (1951) and La terre est ronde (The Earth is round) (1951)—among other paintings on view in this exhibition—to Picabia’s frequent use of a catalogue documenting Romanesque art from Catalonia, published by Barcelona’s municipal museum in 1926. The composition of La terre est ronde (The Earth is round) (1951), for example, adapts key forms from an illustration in a tenth-century illuminated manuscript depicting an angel of the biblical apocalypse, which was reproduced in the Barcelona museum’s 1926 catalogue. In Picabia’s rendition, the multicolored circles suspended in air and arrayed on the ground around the central figure ally this more representational work with the artist’s ‘dot’ paintings. Picabia also appropriated from text, often drawing on Nietzsche for his titles, as seen here in Cherchez d’abord votre Orphée! (First seek your Orpheus!) (1948) and Bonheur de l’aveuglement (Joy of blindness) (c. 1946–1947), both inspired by passages in The gay science (1882).