In Greek mythology, the labyrinth is an architecture of loss: there is no panoramic view, only the immediate present of each corridor, each curve, each wall. This ambiguous, dynamic and stagnant space, both tangible and virtual, is present in the work produced by Roberto Mícoli over the last five decades, and is the central issue for this exhibition in which his most recent works coexist with some early works. The lines, the blocks of color, the joints and folds would be the paths that open up and are interrupted, in almost obsessive repetitions, creating a rhythm of searching and disorientation very typical of his poetics. More than a backdrop, the labyrinth manifests itself in Mícoli's work as a compositional method and, at the same time, as an existential condition.

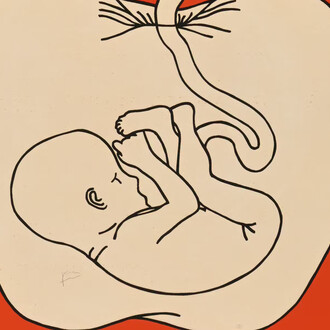

One of the oldest works in the exhibition, Minotaur, by 1989, shows how her visual repertoire was consolidated from drawing, to which she incorporated painting on canvas, sewing and embroidery, cutouts and folds in the textile surface of the support, and objects, many of them toys. Another important aspect is the definition of a constructivist space that provides the basis for her labyrinthine constructions, strongly present in her most recent works. This basis runs through her trajectory as a visual and mental structure, but from it unfolds a universe full of ancestral symbolism and references to elements from diverse cultures, imploding the rigidity of concrete, geometry and a hyperrational pretension. The loose and dangling ends of the embroidery thread, the painted pegs (on or over the canvas), the human silhouettes that interpose themselves like trapeze artists or tightrope walkers.

There is something very subtle in Roberto's work that allows for a suspension in each image, perhaps this is projected from the deep dialogue he sustains with the time of the materials, with the time of the search inherent in the process of constructing and exploding the composition, without it falling apart completely, still maintaining a moment between calculation and loss of control over the volumes, angles and vectors that will guide the gaze. In this sense, the Minotaur, an isolated, imprisoned and feared monster, is the animal and indomitable energy that determines the constant construction of this labyrinthine universe, and he is the artist himself, that which hides, not without noise, in the center of the being, as a dark, vital force.

But in the game that each work stages, the artist also plays the tactical role of Ariadne and gives us a ball of thread to unravel along the way and find the way out. However, nothing drives the bloodthirsty and murderous search for the Minotaur; the labyrinth itself becomes the object of interest—its walls, corridors, and curves—the possibility of getting lost while weaving a landscape of permanence through repetition and care with the internal structure of each work. The volumes and gestures in Mícoli’s work do not seem to attempt to tame this beast, but perhaps to live with it, to hear it reverberating in the material, in the textures, and layers of color that reveal and hide themselves. Instead of a heroic exit, like Theseus’, what his work proposes is permanence in the labyrinth, a type of patient and tactile listening that reverberates from the insistence on embroidering the edges and corners of the walls that hide the voracious and destructive monster.

Emphasizing the images of the Minotaur, the labyrinth and Ariadne's thread, this exhibition proposes a key to reading an entire trajectory that chose not to assert itself through force and impact, but rather by giving in to silence and interiority, hesitating in subtleties, repeating and allowing itself to be traversed by its own gestures. Roberto takes us back to a kind of ritual about the power of seeking and losing oneself in oneself, knowing, living with and caring for the various layers of animality and humanity that are lit up within.

(Texto de Talisson Melo)