Jewelry has been a fundamental aspect of human culture for tens of thousands of years, transcending time, geography, and civilization. From primitive adornments made out of shells and bones to the intricate, high-end designs we see today, jewelry has served multiple roles: a marker of status, a form of artistic expression, a spiritual talisman, and a token of affection. Understanding the history of jewelry is not only a journey through beauty and craftsmanship but also a mirror into the evolving values, beliefs, and aspirations of societies across millennia.

The earliest known pieces of jewelry date back over 100,000 years. Archaeological findings suggest that prehistoric humans strung together simple materials like shells, animal teeth, and bones, often using natural perforations or carving holes. These early ornaments likely had symbolic meanings, signifying social status, personal achievement, or tribal affiliation, or serving protective purposes.

Around 3000 BCE, the civilizations of ancient Egypt began to revolutionize jewelry. Egyptian jewelry was rich in symbolism and materials: gold, considered the flesh of the gods, was particularly prized for its incorruptibility. Semi-precious stones like carnelian, turquoise, and lapis lazuli were meticulously worked into amulets, collars, and rings. Jewelry was not just decorative; it played a vital role in religious rituals and the afterlife, with the dead often buried with their most precious adornments.

Similarly, in Mesopotamia, artisans produced intricate gold pieces decorated with vibrant gemstones. Jewelry here too carried spiritual significance, often invoking the protection of deities. In the Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2600–1900 BCE), jewelry became more sophisticated, with evidence of beading techniques and metalworking skills that rival those of modern jewelers.

Pre-Columbian and Native American jewelry represents some of the most spiritually rich and technically sophisticated adornments in history. Across ancient civilizations like the Maya, Aztec, and Inca, jewelry was deeply intertwined with religion, power, and identity. Gold, considered sacred, symbolized the sun and divine forces, while jade was prized for its association with life and fertility. Techniques such as filigree—the delicate twisting and soldering of fine gold wires into lace-like patterns—hammering, and stone inlay were highly developed long before European contact. In parallel, Native American tribes like the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni crafted intricate jewelry using turquoise, silver, and shell, often embedding profound cosmological symbolism into their designs. Jewelry in these cultures was not merely decorative but a medium to express community ties, spiritual beliefs, and connections to the natural world—a tradition that continues to inspire contemporary artists today.

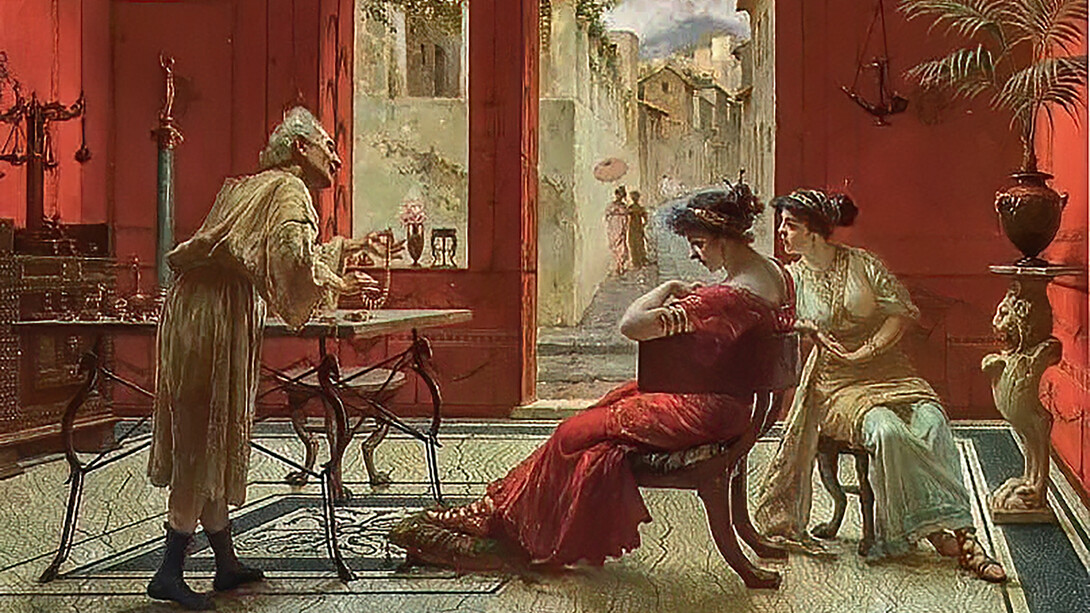

The ancient Greeks and Romans further elevated jewelry into a sophisticated art form. Greek jewelry (circa 1600 BCE onwards) was often inspired by nature, featuring delicate motifs like leaves, animals, and flowers crafted in gold. Jewelry was a display of wealth, but also of culture and education. The Greeks perfected the technique of granulation—soldering tiny gold balls onto surfaces to create intricate, textured patterns without the use of glue or welding.

Roman jewelry, influenced heavily by Greek designs, expanded its reach as the empire grew. Romans wore rings, brooches, and necklaces fashioned from gold, silver, pearls, and colorful gemstones. Jewelry became increasingly available to the affluent middle classes, though sumptuary laws sometimes restricted its use to certain social ranks. Rings, especially, carried significance, with different gemstones believed to protect against illnesses or bring good fortune.

Meanwhile, in Asia, the ancient Chinese crafted extraordinary jewelry from jade, considered more valuable than gold, while Japan developed intricate beadwork and metal ornaments that hinted at their future mastery in delicate craftsmanship.

In the medieval period, jewelry continued to be associated primarily with status and religion. Royalty and nobility adorned themselves with elaborate pieces encrusted with gems. Goldsmiths created intricate crowns, brooches, and rings, often inscribed with religious symbols or set with relics. During this time, the church was a major patron of the arts, and religious motifs dominated jewelry design. Crosses, saints, and biblical scenes were common subjects. Pilgrims often bought or were given small badges or amulets to commemorate their journeys, a tradition that foreshadowed the modern idea of souvenir jewelry.

Interestingly, the medieval period also saw jewelry being used to signify loyalty and political alliances. The giving and receiving of rings and brooches among nobility often sealed treaties, marriages, and alliances.

The Renaissance marked a profound transformation in jewelry design. With renewed interest in classical antiquity and the emergence of humanism, jewelry became more expressive and individualized. Techniques like enameling—the art of fusing powdered glass onto metal to create colorful, durable surfaces—flourished, allowing for vibrant and detailed designs that adorned everything from pendants to royal crowns. Portrait miniatures set into lockets or rings became fashionable, reflecting the growing importance of personal identity.

The discovery of the New World introduced Europe to an abundance of new materials—most notably silver and gold from the Americas. This influx of resources fueled a golden age of jewelry-making. Jewelers in Italy, France, and Spain created sumptuous pieces that were worn as much for show as for their symbolic or sentimental value. Gem cutting also improved significantly, with new faceting techniques that allowed stones to reflect light more brilliantly, enhancing their natural sparkle.

The 18th century saw jewelry becoming lighter and more delicate. Rococo influences favored asymmetrical designs with flowing lines and pastel-colored stones. Jewelry was often worn in sets, known as "parures," consisting of matching earrings, necklaces, bracelets, and brooches.

The Industrial Revolution in the 19th century democratized jewelry to an unprecedented degree. Mass production techniques, new materials like cut steel and jet, and imitation gemstones made jewelry affordable to the burgeoning middle classes. However, handmade, high-quality pieces remained the domain of the wealthy elite.

The Victorian era reflected Queen Victoria’s tastes and the sentiments of the time. Jewelry design during her reign was often symbolic—featuring motifs of love, mourning, and nature. The death of Prince Albert plunged Britain into mourning and popularized black mourning jewelry, often made of jet or onyx.

The 20th century brought about radical changes in jewelry design and meaning. The Art Nouveau movement celebrated organic forms and handcraftsmanship, while Art Deco embraced geometric patterns, symmetry, and bold colors, reflecting the modern industrial age. Innovations in materials—such as the use of plastics, stainless steel, and synthetic gemstones—expanded creative possibilities. Designers like René Lalique, Cartier, and Coco Chanel redefined jewelry as art and fashion, not just luxury.

Jewelry also became more accessible to a wider audience. Costume jewelry rose in popularity, allowing everyday women to enjoy fashionable adornments without the high cost of precious materials. In the post-World War II era, jewelry often reflected optimism and prosperity, with the 1950s and 60s favoring glamorous, sparkling designs. In the 1970s and 80s, individuality and self-expression took center stage, with bohemian styles, bold gold pieces, and statement jewelry.

Today, jewelry is more diverse and democratic than ever before. While traditional fine jewelry—crafted from gold, platinum, and diamonds—continues to thrive, there is also a vibrant world of artisanal, ethical, and even digital jewelry. Consumers are increasingly conscious of sustainability and ethics, seeking conflict-free diamonds, recycled metals, and fair-trade gemstones. The resurgence of handmade jewelry and interest in ancient techniques like hand engraving and enamel work show a deep appreciation for craftsmanship.

Personalization is a key trend—custom pieces, engravings, birthstones, and symbolic charms allow individuals to tell their stories through jewelry. Technology, too, has entered the scene, with 3D-printed designs and smart jewelry that tracks fitness or offers contactless payment options. Jewelry today transcends age, gender, and class. It remains an intimate, deeply personal form of self-expression, a symbol of love, power, memory, and identity.