When I first heard that Claudio Parmiggiani’s work was to be shown at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art in London, I was thrilled that (finally) the United Kingdom would be able to encounter a substantial body of the artist’s work in a perfect location. The works so painstakingly curated for this exhibition present some of the most salient moments from an illustrious career that has spanned more than six decades, and as such, it offers a genuine insight into the materials, processes, and practice of the artist over an extended period. In the light of this, one would encourage viewers to resist any temptation to hastily allocate topical interpretations to the works based on current world events, though in effect such motifs may occasionally be inescapable.

Parmiggiani’s vernacular is born variously out of the hot and heavy alchemy of molten bronze and iron, the dry precision of plasterwork and the sounds of production, and his use of incendiary imagery, dust, soot, and fire-damaged furniture offer a wealth of expansive narrative interpretations, but in defiance of analysis, Parmiggiani creates astonishing auratic objects that move, invite, and inspire. The challenge of introducing Parmiggiani’s work is that it is serious, complex, visually poetic, and profound in its capacity to portray humanity at its best, but also at its darkest. Let’s not pretend that a lifetime of creative production can be distilled into a few hundred words, but try to share some of the interpretive tools and explore the dialogical themes that resonate between the works.

Those who see Parmiggiani’s work for the first time often note four common elements that feature; typically, these elements resolve themselves into materials, objects, processes, and what might best be described as ‘collisions.’

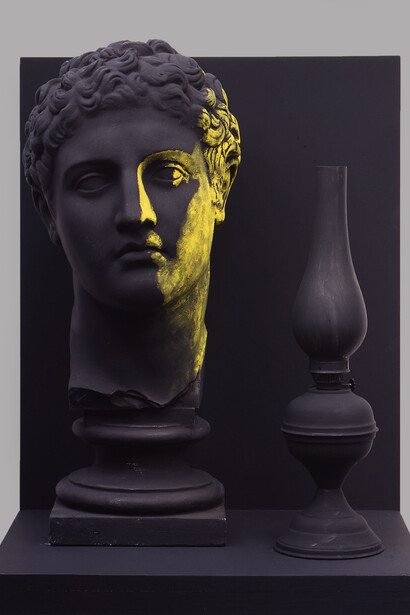

To take the first, Parmiggiani’s material register is extraordinary in its range and diversity: he prizes solidity on the one hand (bronze, lead, stone, wood, plaster) and ephemerality on the other (soot, dust, pigment, ashes).

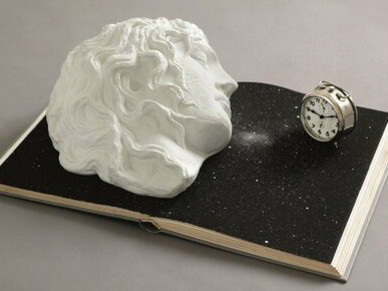

Secondly, Parmiggiani’s objects of choice—statuary, plate glass, bells, anchors, butterflies, et al.—are exquisitely deployed to puncture any whiff of inflated theatricality.

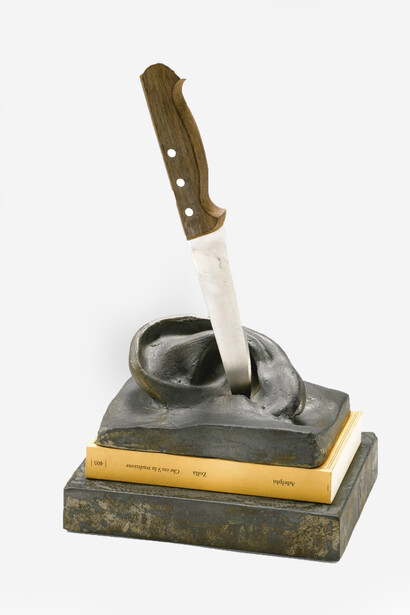

Thirdly, the artist subjects these materials and objects to an array of processes that simultaneously seduce and provoke: books and bottles are burned; glass is shattered on an architectural scale; disembodied heads are blackened with soot or assaulted by knives or saws; classical busts appear irreverently stuffed with maps or are used as pots for old paintbrushes; exhibits are sometimes entirely concealed by dustsheets… I could go on.

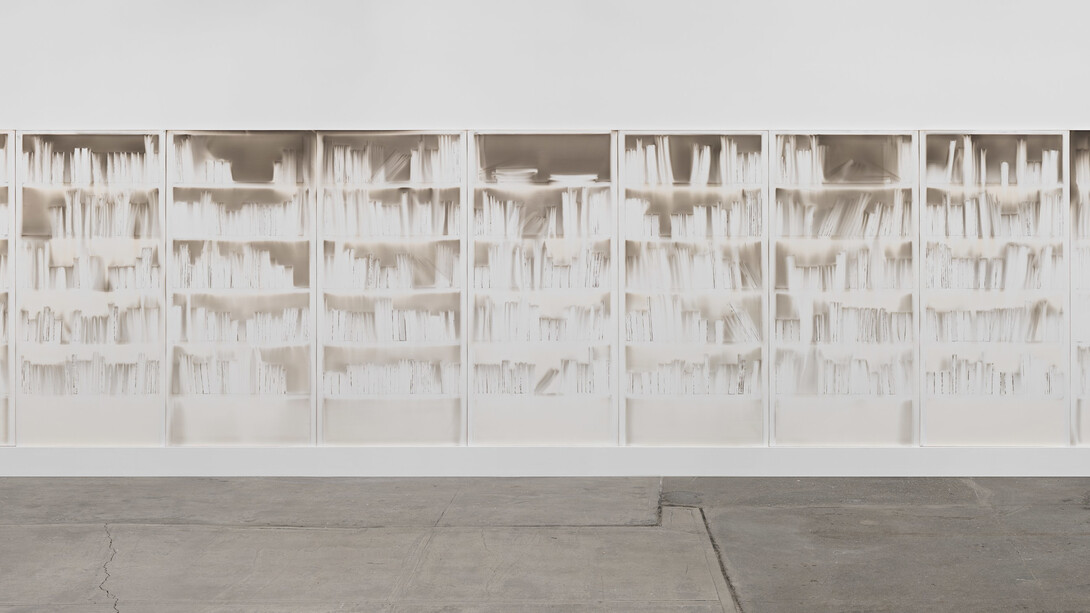

The fourth element that the artist employs to dramatic, some might say iconoclastic, effect is to collide the preceding elements in implicitly traumatic ways: inverted church bells are hung heretically by their clappers, windows are penetrated and burned, and libraries appear vaporized and vanished but for their residual, sooty shadow play.

In decoding the works on show, one might be forgiven for assuming that the artist is himself an iconoclast, but Parmiggiani does not preside over happenstance collisions or the flotsam and jetsam of the incidental. The tableaux he creates are highly orchestrated. Beyond the metaphor of the collision and the resulting damage from impact, incineration, or shipwreck, we are aware of cultural clashes in both series and parallel; in Untitled (2016) the central subject of the photograph is excised by fire, whilst in Untitled (2005) a sheet of staff music notation paper is burned away. In both cases, we remain in crisis as we are left to speculate as to whether their contents were deliberately destroyed to redact the image/music or whether they were cauterized accidentally (one might deduce by some over-enthusiastic scrutineer and the unfortunate positioning of a magnifying glass in sunlight).

A similar metaphorical/metaphysical assembly awaits us in the form of What is Tradition? (1997). Here we witness a cast lead ear pierced by a large kitchen knife atop a book by Elémire Zolla, with the work bearing the title on the spine of the text. The unlikely combination of a kitchen knife, a disembodied and outsized classical ear, a theosophical treatise, and its title is entirely coordinated to generate a puzzle and a narrative. In terms of materiality, the lead of the ear evokes an ironic material relationship between audibility and soundproofing; the knife violently pierces the deafness of history (tradition) whilst sitting on the question posed by Zola’s text.

Parmiggiani’s work offers its audiences a rare choice: on the one hand, it invites viewers to refer to history, semiotics, classicism, and material culture in order to discover the deconstructed narrative(s). On the other hand, learned research is not a prerequisite for enjoyment, as the exquisite visual poetry and physical presence of the works are enough to charm and compel.

Accompanying the other works in the space, the series of windows made impenetrable by soot and damage also serves as confirmation that we are immersed in the spectacle of the show, in much the same way as Parmiggiani’s earlier Shipwreck with Spectator. This approach is typical of Parmiggiani in placing the audience on the horns of a dilemma: as visitors to an exhibition of art, we are expected to make an appreciation, but Parmiggiani asks us to involuntarily bear witness to thinly veiled catastrophes, each offering episodic views into much darker worlds. These are worlds inhabited by melancholy, tragedy, conflict, and mortality, where the diaphanous garb of civilization and the vestigial benevolence of human nature are, in turn, snatched and rent asunder.

I must say something, of course, about his most resonant and haunting serial installations, namely the Delocazioni. I have seen this term translated as ‘delocations,’ ‘displacements,’ or even ‘dislocations.’ In all honesty, I think the true interpretation may lie somewhere in between such competing terms. Having seen Delocazioni in various forms, dimensions, and locations over the past decade, I never fail to be overwhelmed by the potency of their silhouetted books, bottles, butterflies, et al. The qualities of these works are simply breathtaking in their fugitive evocation of the missing, the absent, and even the redacted.

The quick and dirty scholarly references steer us back to the German Student Union book burnings in Austria in the 1930s, and for my generation, media images of burned books have become a totemic preamble to the Holocaust and further image associations with the atomic aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These are false ‘recollections,’ of course, and are not my own, but are ‘real’ as memories of media images lent credence by the passage of time. For children of the 1960s, who grew up with war documentaries such as the classic The World at War, book burning was to the Holocaust as broken glass was to Kristallnacht: an algebraic, if you like, for intolerance and persecution on unimaginable and cruel numerical scales.

Parmiggiani reminds us that, sadly, some things remain immutable. A show that has to be seen.