The 1980s were a tumultuous period for Yugoslavia. The economic conditions were deteriorating, and nationalist movements were becoming more prominent. Perhaps most significantly, Josip Broz Tito passed away in 1980. With the famous description of Yugoslavia being “6 republics, 5 nations, 4 languages, 3 religions, 2 scripts, and one Tito,” his death held great significance. As a federal republic, the country had already experienced political decentralisation, particularly since the 1950s, and had adopted a worker self-management style economic system to overcome production inefficiencies. Nonetheless, economic difficulties continued, alongside a mounting foreign debt crisis.

The economic problems in Yugoslavia highlighted ethnic divisions, as inequality and ethnicity were closely linked. However, unlike the rest of the country, Slovenia and Croatia flourished because of open borders and tourism, which led them to seek greater autonomy and decentralisation. They felt that their economic progress was being exploited to help poorer regions. Despite attempts to lessen economic inequality, these efforts failed and resulted in a rise in foreign debt.

In the northern regions, there were debates about the central authority’s management of resources, which contrasted with the struggles against poverty in the south, particularly in Kosovo. As the poorest region in Yugoslavia, Kosovo desired greater support from the central government while also seeking more autonomy. While Albanians were the majority of the population, it’s important to remember that Serbian influence was considerable in the province’s administration. This created serious tensions between ethnic Albanians and Yugoslav and Serbian authorities, dating back to the 1960s.

The 1974 Constitution, enacted to address unrest, decreased Serbia’s control over its autonomous region of Kosovo, granting Kosovo autonomous province status. Although autonomous, Kosovo possessed its own constitution, assembly, and even veto power over federal matters, granting it near-equal status to the Socialist Republic of Serbia. Therefore, Albanian authorities made repeated requests for Kosovo to be formally recognised as a constituent socialist republic within Yugoslavia. This request was seen as a significant danger to Serbian national identity since it had the potential to de-Serbianise Kosovo, a place of great importance in Serbian history and national mythology. The Battle of Kosovo (1389) against the Ottomans took place in this region and its memory embodies a powerful mix of religious zeal, nationalism, and national pride.

The tensions in the region reached their peak during the 1981 demonstrations, which marked a turning point. It started as a student protest for better cafeteria food, but grew into a larger movement for Kosovo’s increased status within Yugoslavia. The protests were eventually brought under control with the use of force and thousands of soldiers. However, instead of suppressing the movement, this actually strengthened it and it transformed into a national movement. The conflict continued to spread after 1981. During this time, many Albanians faced accusations of plotting against the state, and a significant portion of Yugoslavia’s political prisoners were Albanian. Moreover, the Kosovo Albanians’ demands also prompted counter-protests and petitions from Kosovo’s Serbian population.

A disturbing incident, unlike any other, garnered intense media attention in Yugoslavia during this period of ethnic unrest. In May 1985, a 56-year-old Serbian farmer named Djordje Martinović was reportedly assaulted by two Albanian men while working in his field. They beat him, tied him up, and inserted a beer bottle into his rectum. Martinović lost consciousness but crawled to the nearest hospital after regaining consciousness. Despite the story being based solely on Martinović’s allegations, the media sensationalised it to rally Serbs, presenting it as a verified fact. The media presentation of the event fuelled anti-Albanian feelings in many areas.

Local authorities initially believed Martinović’s story and launched an investigation accordingly. Subsequently, they retracted their initial assertion, explaining that the incident resulted from an accident during sexual activity when the bottle, balanced on a wooden stick, unexpectedly broke. Certain officials, including a military colonel, spoke directly with Martinović. They stated Martinović admitted the incident was accidental during a personal satisfaction act. Doctors also provided reports supporting this explanation. Meanwhile, to avoid fuelling ethnic conflict and jeopardising the central ideology of “Brotherhood and Unity,” Yugoslav state media and authorities adopted a neutral position. However, this displeased the society, particularly in Serbia, where the public demanded more information and a better explanation. For many, the state was hiding the true nature of the case.

The situation was further complicated by the experts’ conflicting views. It was reported by the local authorities, primarily Albanian, that the injury was self-inflicted. The Belgrade military hospital, where Martinović received further care and investigation, concluded that his wounds were inconsistent with self-infliction. Ironically, the investigative expert group created for this case determined that the injuries could have been either self-inflicted or caused by others—essentially confirming nothing. The local and federal views on the case differed, which made it seem even more through ethnic. Serbs interpreted the case as evidence of the federal government’s inability to protect them, blaming Kosovo’s judicial independence in criminal matters and alleged anti-Serb sentiment.

Many newspapers subsequently reported that local Kosovar authorities, predominantly Albanian, inadequately investigated the attack, shielded the perpetrators, and coerced Martinović into a false confession. Allegedly, Martinović was promised state jobs for his kids if he claimed responsibility for his injury. The Martinović family, responding to national media coverage, insisted on Djordje’s innocence, highlighting his status as a grandfather and lack of his prior involvement in similar actions for self-satisfaction.

The case remained unsolved despite extensive investigations. Still, to the public, the criminals were clearly Albanian, and the Kosovar authorities appeared to be protecting them. Some newspapers blamed ethnic Albanians, claiming the violence was typical of Albanian nationalism. It was rumoured that some Albanians, seeking revenge for a family member’s death in prison, attacked the first Serb they saw, who happened to be Martinović. However, although such rumours spread like wildfire, no concrete evidence emerged.

According to Julie Mertus, author of “Kosovo: How Myths and Truths Started a War,” which devotes a whole chapter to Martinović, the Albanians’ actions shifted from being viewed as anti-Yugoslav or anti-socialist to being seen as purely anti-Serbian after the event. The narrative of victimisation of Kosovo Serbs intensified during this period, and such assertions persist even now.

Consequently, the Martinović case became far more significant than a simple criminal case. Conflicting medical reports make it almost impossible to determine exactly what occurred. The identity of the responsible party is not important anymore. What is important is how this case shows that national and historical narratives can be activated and altered, even in the most unusual circumstances. Martinović’s case exemplifies several key aspects of such a process. First, the terrible condition of Martinović was regarded similar to practices of impalement under the Ottoman rule.

The impaling of several Serbian rebel leaders by local Ottoman authorities in the 19th century deeply affected Serbia’s national mythology about five hundred years of Turkish rule, despite the rarity of this practice. The famous Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU Memorandum) in 1986 declared that the Martinović case “is reminiscent of the darkest days of the Turkish practice of impalement.” For many, Djordje Martinović’s “impalement” by a beer bottle symbolised this lingering trauma of the past.

The second point is that many Serbs left Kosovo because of ethnic, political, and economic difficulties at this time, causing a large amount of their property to be transferred to Albanians. To Serbs, transferring Serbian property to Albanians represented a potent symbol of ethnic cleansing. For them, Kosovo held immense symbolic weight, and the idea of a Serb-free Kosovo was simply unacceptable. As such, accusations of forced displacement by Albanians circulated, further deepening the mistrust between the two communities. Some rumours surrounding the Martinović case suggest Albanians offered to buy his valuable land, and his refusal led to his brutal torture. This rumour, and similar stories, whether true or not, fuelled a sense of fear and injustice among the Serbs. The notion that their own people were being forcibly removed from their ancestral lands intensified the existing animosity and solidified the belief that their presence in Kosovo was under threat.

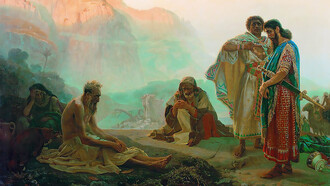

Thirdly, the narrative surrounding Martinović presented him as a Serbian martyr, allegedly persecuted for his Serbian heritage. Writers have frequently compared him to Serbian victims across various historical periods, including Habsburg and Ottoman rule and the German occupation of the 1940s. For example, some compared the situation to the Jasenovac Concentration Camp, where many Serbs perished during World War II. The victims associated with the Martinović case included not only Serbs but even Jesus. A Serbian painter, Mića Popović, created a painting called The Crucifixion of Djordje Martinović, where Martinović is presented as Jesus being crucified (despite the painting being inspired by de Ribera’s The Martyrdom of Saint Philip). However, the characters are different—near Martinović, there are not Jews but Albanians with their traditional hats, and there are no Romans but Yugoslav police. Finally, a noteworthy detail is present on the ground: a bottle.

Since religious and national symbols were connected to the Martinović incident, the name of Martinović was repeatedly invoked to justify cases against Kosovar Albanians. The incident, thus, did not fade quickly from memory. The first edition of a nearly 500-page book about the incident sold out—all 50,000 copies. After years of incidents, media reports repeatedly highlighted his ongoing suffering and the absence of financial support from local Kosovar authorities for his treatment. Martinović died in 2000 at 71.

The Martinović case had a significant impact on Yugoslavia in its final years. Many did not focus on the actual criminals or victims involved. Instead, they saw them as symbols of entire nations. The case became a tool for the nationalist rhetoric of ethnic politics. Four years post-incident, Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević addressed Serbs during the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo in the field where the battle took place, declaring, “Six centuries later, now, we are again engaged in battles and are facing battles. They are not armed battles, although such things cannot be excluded yet.”

His words proved prophetic—soon after, the Yugoslav Wars erupted. Serbian paramilitaries carried out civilian massacres and war crimes, first in Croatia and Bosnia, and later in Kosovo during the Kosovo War. As a result, thousands of people lost their lives, and many more were forced to flee their homes. In the end, the Djordje Martinović debate was not really about him, but the stories people told, which hinted at the violence to come.