Thou hast to study the voidness of the seeming full, the fullness of the seeming void.

(H.P. Blavatsky)

Adams and Ollman is pleased to present The Fullness of the Seeming Void, a cross-generational group exhibition that explores different ways that artists visualize and manifest the unknown. While spirituality and mysticism’s influence on modern abstraction has become more widely recognized, this exhibition will explore a lineage of personal and sensory investigations into the hidden forces that shape our world. The drawings, paintings, photography, and sculptures from the 1960s to the present that make up this exhibition locate cosmologies and voids, the enormous and the infinitesimal, the exceptional and the mundane.

The artists included in the exhibition engage with various histories and fields of study, as well as different modes of making—diagramming, mapping, embellishing, patterning, world-building—in a quest to identify universal connections with personal truths. While tackling grand abstract concepts, they find relevance and meaning in the minutiae and details of our everyday lives. Each of the works included in The Fullness of the Seeming Void attempts to capture or represent that which eludes institutionalized knowledge systems, relying instead on embodied experience and intuitive logic to picture the void and the unknown.

About the artists

Bettina (b. 1927–2021, Brooklyn, NY) lived and worked in the Chelsea Hotel from the 1970s until her death, generating a substantial body of conceptual work over several decades. She captured a profound experiential understanding of the city, one that allowed her to decipher and locate patterns in the rhythmic fluctuations of urban life. Heavily influenced by mathematical theory and Jewish mysticism, Bettina believed her observations were a gift and that was her responsibility to record and translate them.

Her series Phenomenological New York (c. 1970s–c. 1980s) on view in The Fullness of the Seeming Void represents a version of New York City as she saw it, refracted in the architectural distortions of mirrored building facades. In her works, the city buckles, twists, stretches, ripples, or fragments into pattern. Sometimes she arranged them in linear montages, other times in grids, rotating them like quilt squares. For her, these works unveiled an “invisible secret” made tangible through newly perceived spatial dimensions. After MoMA PS1’s Greater New York and Yto Barrada’s A Raft at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, both in 2021, this is one of the first times Bettina’s work has been presented in a group context.

A pioneering American artist and one of the most widely recognized female artists of the 1960s, Lee Bontecou (January 15, 1931–November 8, 2022) drew enigmatic universes filled with ominous voids, black holes, halos of lines, and sharp edges that connect inner and outer worlds. Bontecou’s cosmologies feel like a supernova event, a powerful and luminous explosion where beginning and ending, death and rebirth, emptiness and possibility can exist simultaneously. While many align her work with second-wave feminism, Bontecou maintained that her sculptures, paintings, and drawings of cavities reflected her excitement about the images of outer space that were captured at the start of the space age.

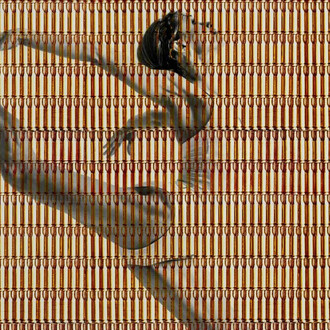

Cynthia Carlson’s (b. 1942, Chicago, IL; lives and works in New York, NY) iconoclastic paintings and works on paper play with all-over compositions that are derived from patterns, architecture, and common objects that define the artist’s everyday environment. In the 1970s, Carlson traveled widely to document environmental works by self-taught artists. These travels inspired a body of work that was significant for the Pattern and Decoration movement—one that pushed the boundaries of traditional painting and disregarded the hierarchy between fine and decorative art. Continuously driven by the inquiry: “What is an edge and why is it there?” Carlson locates patterning as a particularly useful tactic for exploring notions of infinite expansion beyond the boundaries of the picture plane.

Time is both material and subject matter in the work of Abigail DeVille (b.1981, New York, NY; works in the Bronx, NY and Kearny, NJ), whose sculptures and installations of discarded objects conjure vast universes by accumulating forms, binding objects, and patinating their surfaces. Throughout DeVille’s work, the material presence of previously used objects creates gravitational force. In The Brief Thread of a Star’s Brilliance II.XXVII.MCMXCIII, a blackened watch case contains a miniature nebula composed of wire, jewelry, bones, and photographs. DeVille draws connections between the domestic detritus she collects and planetary matter that has existed since the beginning of time. Her work honors the lost histories that live on through her found materials, urging a confrontation with whitewashed versions of American history and generating questions such as: whose labor and actions become elevated to the historical record over others, and what are the consequences of this memory loss?

Covey Gong (b. 1994 Hunan, China; lives and works in New York, NY) explores the social history of objects in order to understand how meanings emerge through material expression. His complex structures crafted from metals, textiles, and fiber investigate the capacity of garments and architectures to encapsulate their subjects and imply personhood. Gong incorporates woven panels and sheathing wrapped around skeletal armatures to articulate voids and form as well as instances of collapse. Their postures evoke mechanical and bodily apparatuses in their resting state and suggest the potential for activation or possession while their cosmological networks imply an underlying logic.

At once visually graphic and materially alluring, Nina Hartmann’s (b. 1990, Miami, FL; lives and works in New York, NY) cryptic semiological systems propose visual images and symbols as articulations of institutional power. Drawing from photographic archives, Hartmann selects images that have served as veridical evidence for conspiracy theories or unexplained phenomena and organizes them onto glyphic, candy-colored panels evocative of religious symbols or institutional building plans. In How to Become Untraceable (for PH), cropped images allude to wildlife tracking systems and technologies. Collectively, her tactile and enigmatic diagrams effectively channel both the wonderment and anxiety that accompany technological advancements of image-based data while speaking to a historical desire to harness truth and meaning through systems of belief.

Heidi Lau (b. 1987, Macau, China; lives and works in New York, NY) builds immersive ceramic worlds and totemic objects that figure time as a malleable material akin to clay itself. Lau reaches back to her ancestral past for narratives—ancient Taoist mythologies and folklore—and manifests them into the present day in the form of ruins, funerary vessels, and fossilized creatures. Glossy tendrils in the Cave of Chrysalis evoke fire, icicles, or fingers wrapped around pearls of mercury, an element that was historically coveted by Chinese emperors who were seeking immortality. Embedded in the crevices here like seeds or spider eggs, they indicate an impending and potentially lethal proliferation. Her earthen objects are also roving markers of place; rhizomic manifestations of distant histories and geographies regenerating in the here and now.

Kate Newby’s (b. 1979, Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand; lives and works in Floresville, TX) sensitive sculptures are the result of her careful and astute observations of the quotidian that often take the form of an architectural interventions such as tiles, windows, or floors, or collaborate with the natural elements—chimes moved by the wind, channels that navigate the flow of water, or puddles that accumulate rain or snow. For the exhibition at Adams and Ollman, Newby will exhibit Wild Owns the Night, a floor sculpture that consists of hundreds of small ceramic forms glazed in a gradient of color, each the repository of repurposed broken glass that once fired is given a second life. Newby’s site-specific arrangement recalls a scatter plot, a murmuration, or a constellation of stars.

For nearly five decades, Lynne Woods Turner (b. 1951, Dallas, TX; lives and works in Portland, OR) has given shape to the hidden, the obscure, and the mysterious. Composed of meditative linework and subtle color, and referencing the female form, patterning, cellular structures, systems of language, and mathematical diagrams, Turner’s intimate drawings function, at times, like intuitive schematics for that which is ultimately unknowable. She often executes her drawings on antique book paper, treating their creases and tendency to buckle as structural components that inform her interventions. The space of Turner’s works on paper is both positive and negative, inner and outer, personal and public, as well as an entity, a subject, and a conceptual framework.

Stefanie Victor’s (b. 1982; lives and works in Queens, New York) sculptures are distillations of her affective, private experiences with domestic objects and space, studio process, and materials. Gestures such as turning or folding are made manifest in Victor’s intimate sculptures. We often expect a sculpture to radically represent our reality, but Victor turns that assumption on its head by presenting us with objects that closely resemble an original reference, but with curious disjunctures or discrepancies. On view in The Fullness of the Seeming Void are three works, all titled Tiffanie’s Clock, that consist of multiple components set directly into the wall.

Arranged in a circular form resembling a gear or mechanism, indented elements made from charcoal and cement support a handspun loop of wool that has no knot, twisting into infinity. Slight differences in the installation among the three allude to the passage of time, although there are no clear forwards or backwards, no beginning or end. Instead of being manufactured, elements are carefully but imperfectly realized by hand; instead of being useful in any conventional sense, they invite a sense of abstract activation that might feel quietly charged, bodily, taut, or tenuous. Installed like a spatial notation or score, they are ultimately in the service of access to a nuanced, even covert register of expression and experience.

Stella Zhong (b. 1993, Shenzhen, China; lives and works in New York, NY) creates paintings of secret worlds and charged relationships that display vantage points calibrated to both cosmic and microscopic scales. Her stark paintings of objects—planets, holes, unknown infrastructure—might confront and alarm us or seek intimacy and understanding. They exist without context, in uncertain spaces that often have abrupt scale shifts, sometimes aloof and often with agency. Some have cold, clinical passages of paint, others are rendered with energetic and frenetic brushwork. In total, Zhong’s spaces are empty, their purpose ambiguous and their logic obscured, leaving the viewer staring into a vast picture plane of the unknown.