You might not notice it at first. But the atmosphere upstairs is cool-white, ever so slightly off, artificial. A mood is set, at once alienating and charged, in a space in which a voice seems to address you. Quickly you realize that this voice—in turns questioning or plaintive—speaking over the moving images of Shahryar Nashat’s Image Is an Orphan is, in fact, in conversation with itself. You are not being addressed at all. Instead, the video’s voice-over speaks in a competing monologue, as if it were the Image itself, who sounds raspy and world-worn, speaking aloud to the Body, who answers back with her almost cinematictimbre.

“How will I die? Who will carry me? Who will feel my after-effects?” the Body im- plores (but it could just as well have been the Image talking). Speaking on behalf of con- cerns as much human as technological, this confusion of body (a being of “water and cells”) and image (a pixilated combination of mere “zeroes and ones”) is typical of the Swiss artist’s larger project.

Mobilizing sculpture, photography, installation and the moving image, Nashat’s work of the last decade has persistently probed how the human body desires and signifies, how it longs and loses itself. Indeed, the body’s aliveness, its sensuality, vulnerability, contingency, and ultimate mortality, as well as its technological mediation—photographically, digitally, prosthetically, or even pornographically—are central to so many of Nashat’s pieces. His exhibition, The Cold Horizontals, comprising all newly commissioned work, is no exception.

In its central work, the eighteen-minute Image Is an Orphan, the camera lingers on a mysterious, trembling surface, veined and glistening. What is pictured is a simulation of retinal imaging, revealing the interface between your eye and brain, that neurological site at which visual cognition occurs, indeed, the decisive place for an image—any image—to assemble in your mind. But before you have deciphered this corporeal image-maker, the video has restlessly cut to various looped black and white Internet clips of “hazards,” showing bodies in states of accidental violence: falling, fainting, or smacking into walls, rails, or other objects harder and less vulnerable than themselves. To watch those captured points of impact is to constantly resist the urge to cringe and look away.

Image Is an Orphan, Nashat’s noir work, appears across eight monitors, their functional form undisguised, and the screened image palpably tangible, decidedly not a flickering, immaterial projection of light and dust. The video mixes technoid medical imagery with incidental ama- teur footage just as it mixes the aforementioned voice-over with a movie-like soundtrack (you are almost defenseless against its subtle emo- tional manipulation, and that seems precisely to be the point). Recurring throughout are what appear to be references to two iconic artworks.

Across his practice, Nashat has been preoccupied with the art of others, featuring them in what seem like cinematic cameos. Here you might detect evocations of Felix GonzalezTorres’s 1991 image of an empty unmade bed, “Untitled”, and Andy Warhol’s 1964 Electric Chair, based on a press image of an electric chair set in a room used for executions. Both those artists’ images are set in spaces where the body is absent yet implied. “Dead bodies,” these artworks say without saying anything at all. “Dead bodies,” the voice in the film announces again and again in relation to yet other images.

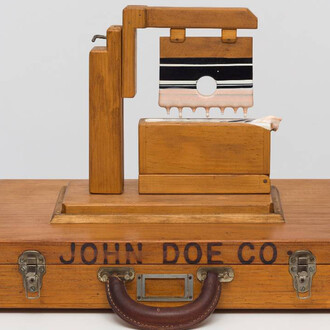

Accompanying the film are three colorful cast sculptures that appear like eerie takes on Minimalism, here looking ever so slightly deflat- ed and marred (by bite marks, or through the revelation of their “muscles,” as the artist calls the nervy-glossy edges). Cold Horizontal (IMAGE) and Cold Horizontal (BODY) are laid out on top of Saran-wrapped bases, insis- tent in their horizontality, so much so that the twinned elements might seem to wait for autopsies to be performed upon them, while in a back room Cold Horizontal (GHOST) rests on its side, buttressed by metal brackets. As did Constantin Brancusi before him, Nashat eliminates the hard distinction between sculpture and its supporting devices, rendering braces or base elements integral to the work itself.

The techniques Nashat deploys in the creation of his works signify in crucial ways. The indexicality of cast and replicated forms proliferate in his sculptures and the index operates also in the wall work Yea High ( for Hunter’s Right Shoulder) that received the sweaty imprint of a shoulder leaning on its sensitive plaster center. In After-Effects of the Tear (RAW IMAGE), Nashat uses a new UV printing technology that embeds the photographic image of a tear-drop lined face in the surface of a plaster slab. Not only does photography here become sculptural, but the body at the core of Nashat’s project literally melds with the photochemical surface of the image—body become image become sculpture. The video, for its part, concludes with a close-up of a hired heartthrob actor’s face and shirtless upper body, appearing so highly pixilated as to be unrecognizable and only slowly coming into focus. The actor’s is a body that knows how to act like an image.

In a back room lies the uncanny sculpture Player, a cloth-covered form, modeled on a crash-test dummy and crumpled on the floor, at once a flaccid, passive victim and pliably ready for anything. Death seeps from everything in The Cold Horizontals, without allowing us to forget that the dialectic between death and desire remains as strong as between the body and the image that is meant to memorize it. Because even after death (of the body), images live on. And the Body, Nashat tells us, futilely strives for the same everlastingness. Its refrain pervading the film, the Body’s voice relentlessly demands an answer of the Image: “How will I die? Who will carry me? Who will feel my after-effects?”.

Shahryar Nashat was born 1975 in Geneva, CH; he lives and works in Los Angeles, USA.