The notion of "really useful knowledge" was originated from the workers' awareness of the need for self-education in the early 19th century. In the 1820s and 1830s, workers' organizations in United Kingdom introduced this phrase to describe 'unpractical' knowledge like politics, economics and philosophy, as opposed to what factory owners proclaimed to be “useful knowledge”. Some time earlier capitalists began investing in advancement of their businesses through funding the education of workers in 'applicable' skills and disciplines such as engineering, physics, chemistry or math.

Through this reference to the beginnings of struggle against exploitation and the early efforts towards self-organized education of workers, the exhibition “Really Useful Knowledge” looks into issues around education from contemporary perspective.

The exhibition does not point towards one ‘correct’ method of education, of learning or (co)learning, but rather presents a range of strategies and methodologies through which artists deconstruct the ‘common knowledge’ and hegemonic views on history, art, gender, race, and class.

The position that the exhibition is promoting is strongly against dismantling of public education, even though it acknowledges that schools are also instruments of class rule and alienation, and this contradiction figures in variety of approaches proposed by the works presented in the exhibition. Really useful knowledge insists on the role of public education in achieving general conditions necessary for 'citizens' to 'govern'. At that it relies on the principle of learning by teaching and teaching by learning, and stands on the position that real learning is possible only in self-governed, autonomous situations.

In that respect, it is not by accident that Really Useful Knowledge includes numerous collectives and self-organized principles of collective learning, collectives like Russian group Chto delat, Subtramas, Mujeres Públicas or Iconoclasistas, to name just a few.

Chto Delat? initiates interventions examining the role of art, poetics, and literature in educational situations and integrate activism into efforts to make education more politically based. Their work Study, Study and Act Again (2011) functions as an archival, theatrical, and didactic space, created to establish interaction with visitors to the exhibition. Many of the publications included in the Chto Delat? installation are published by the Madrid based activist collective and Spanish independent publishing house Traficantes de Sueños.

The activist and feminist collective Mujeres Públicas (Public Women) engages with various issues connected to the position of woman in society. One of their permanent causes is the political struggles around abortion legislation in Latin America. The group’s project for the exhibition gathers the recent material from their actions and protests in public space.

The work by Argentinean artistic duo Iconoclasistas uses critical mapping to produce resources for the free circulation of knowledge and information. Their maps, built through collective research and workshops, summarize the eff ects of various social dynamics, such as the colonization of South America, the history of uprisings on the continent, and the urban developments brought about by neoliberal politics.

The group Subtramas has included organizations and activists from all over Spain in a project developed in dialogue with the exhibition. Social actors such as self-education groups, occupied spaces, independent publishers, collective libraries, activists groups, social centers, theorists, poets, LGBT activists, and feminists will take part in assemblies, readings, discussions, and various public actions.

In the other hand, artists have often attempted to analyze the way in which the education system acts as the primary element for maintaining social order and the potential for art to develop progressive pedagogy within existing systems.

Work Studies in Schools (1976–1977) by Darcy Lange documents lessons in the classrooms of three schools in Birmingham, England. The project uses the promise of video’s self-reflectivity and interactivity in its early years to expose class affiliation and the ways in which education determines future status in society.

While working as a teacher of visual arts in a high school in Marrakesh, artist Hicham Benohoud took group photographs of his pupils in the carefully posed manner of tableaux vivants. The Classroom (1994–2002) creates surrealist juxtapositions of pupils’ bodies, educational props, and strange objects, while students’ readiness to adopt the curious and uneasy postures opens up themes of discipline, authority, and revolt.

En rachâchant (1982), a film by Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, humorously looks into dehierarchizing the educational process by showing schoolboy Ernesto, who insistently and with unshakable conviction refuses to go to school. Two Solutions for One Problem (1975) by Abbas Kiarostami, a short didactic film produced by the Iranian Centre for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, is a simple pedagogical tale of cooperation and solidarity that shows how two boys can resolve the conflict over a torn schoolbook through physical violence or camaraderie.

In Postcards from a Desert Island (2011) Adelita Husni-Bey organized a workshop for children of an experimental public elementary school in Paris, in which the students built a society on a fictional desert island. The film shows the children’s self-governance quickly encountering political doubts about decision-making processes and the role of law, echoing the impasses we experience today, but it also shows the potential and promise of selforganization. Really Useful Knowledge reiterates the necessity of producing sociability through the collective use of existing public resources, actions, and experiments, either by developing new forms of sharing or by fighting to maintain existing ones now under threat of eradication. Public Library: Art as Infrastructure (2012) by Marcell Mars is a hybrid media and social project based on ideas from the open-source soft ware movement, which creates a platform for building a free, digitized book repository. In that way, it continues the public library’s role of offering universal access to knowledge for each member of society.

One way of thinking of 'really useful knowledge' in relation to art and the notion of pedagogy as a crucial element of organized collective struggles is to think of direct 'usefulness' of art and its infrastructure, and indeed there are works in the exhibition that might be understood as directly useful, like, for example, Autonomy Cube, the work by artist Trevor Paglen and computer researcher and hacker Jacob Appelbaum, which offers free, open-access, encrypted, Internet hotspot that route traffic over the TOR network, which enables private, unsurveilled communication. But like in that work, which visually references minimal sculpture, the exhibition as a whole is more interested in the tension between art’s utilitarian and aesthetic impulses, between perceived need for active involvement and insistence on the right of art to be “useless”.

Alll the works presented in the exhibition are occupied with the transformative potentials of art and effects and potentialities of images, in relations to themes like colonialism and its legacy, legacy of Cold War and instrumentalization of culture, or formation of revolutionary subjectivities - often evoking usefulness of particular historical moments in relation to present struggles.

In this sense, originally produced for Algerian state television, How Much I Love You (1985) by Azzedine Meddour is an ingenious mixture of the genres of educational film, propaganda, and documentary. Meddour uses excerpts from advertising and propaganda films found in colonial archives, expertly edited with a distressingly joyous soundtrack and turned on their head in an ironic chronicle of colonial rule and the French role in the Algerian War of Independence.

The Mozambican Institute by Catarina Simão researches the film archives of the Mozambican Liberation Front, or FRELIMO. As a part of their struggle against Portuguese colonial rule, and in an attempt to fight illiteracy, FRELIMO created the Mozambican Institute in Dar es Salaam in 1966 to enable study outside of the educational framework organized by colonial rule. Working with the remains of the institute’s f lm archive kept in Maputo, Simão reinterprets and researches this heritage in which political struggle intersected with radical educational and artistic ideas.

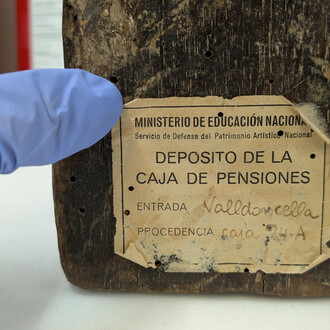

The installation Splinters of Monuments: A Solid Memory of the Forgott en Plains of Our Trash and Obsessions (2014) by Brook Andrew includes a wide assortment of objects: artworks from the Museo Reina Sofía, artworks borrowed from the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Museo de América, records from local community archives, and paraphernalia such as postcards, newspapers, posters, rare books, photographs, and smaller objects. Their juxtaposition challenges hegemonic views on history, art, gender, and race.

The possibility of renegotiating relations of colonialism and power through engaged acts of viewing and by bringing a hybrid social imaginary to the symbolic site of the museum is also explored by This Thing Called the State (2013) and BetweenWorlds (2013) by Runo Lagomarsino, works that rely on historical narratives related to the colonial conquests of Latin America and the question of migration. Looking into how society relates to its past and projects its identity, Lagomarsino borrows a collection of retablo votive paintings commissioned by Mexican migrants after their successful illegal crossing of the border to the United States.

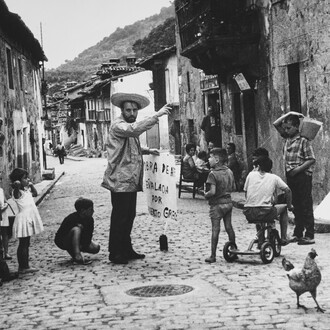

In Cecilia Vicuña’s What Is Poetry to You?—filmed in 1980 in Bogotá—the artist asks passers-by to respond to the question posed in the work’s title. The answers offer personal definitions of poetry that are opposed to racial, class, and national divisions Working closely with organizations for the rights of immigrants, Daniela Ortiz developed Nation State II (2014), a project engaged with the issue of immigration, specifically with the integration tests required for obtaining residency permits.

Looking into ideological shift s that change how the relevance of particular knowledge is perceived, marxism today (prologue) (2010) by Phil Collins follows the changes brought about by the collapse of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in the lives of three former teachers of Marxism-Leninism, a compulsory subject in all GDR schools that was abolished along with state socialism at the time of German reunification. The teaching of Marxism-Leninism, as described by the interviewed teachers, comes across as an epistemological method and not just a state religion whose dogmas were promulgated by a political authority. In use! value! exchange! (2010), Collins films a symbolic return in which one of the former teachers gives a lesson on basic concepts of surplus value and its revolutionary potential to the clueless students of the University of Applied Sciences, previously the prestigious School of Economics, where she taught before the “transition.” The students’ ignorance of the most basic of the contradictions Marx discovered in capitalism— between use value and exchange value—is indicative of the present moment in which capitalism stumbles through its deepest economic crisis in eighty years.

Several works in the exhibition deal with the modernist legacy and the present-day implications and reverberations of culture having been used as a Cold War instrument. Starting from a reference to the iconic exhibition Family of Man, first organized at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1955 and later circulated internationally, Ariella Azoulay’s installation The Body Politic—A Visual Universal Declaration of Human Rights (2014) deconstructs the notion of human rights as a post-WWII construction based on individualism, internationalism, humanism, and modernity that at the same time also contributed to the formation of the hegemonic notion of otherness. By reworking the original display of Family of Man, Azoulay shows the cracks in its representation system and asks what kind of humanism we need today to restore the conditions for solidarity.

The visual archive of Lifshitz Institute (1993/2013) by Dmitry Gutov and David Riff centers on rereading the works of Russian aesthetic philosopher Mikhail Lifshitz, one of the most controversial intellectual figures of the Soviet era. Opening in Moscow by D. A. Pennebaker documents impressions of the American National Exhibition organized by the U.S. government in 1959 in order to propagate the American way of life. By portraying the rendezvous of Muscovites and American advanced technology, it shows a propaganda machine gone awry: while the exhibition attempted to lure the audience with a “promised land” of consumerism, the documentary presents differences as well as similarities between American and Russian working-class life.

In his film June Turmoil (1969), Želimir Žilnik documents student demonstrations in Belgrade in June 1968, the first mass protests in socialist Yugoslavia. Students were protesting the move away from socialist ideals, the “red bourgeoisie,” and economic reforms that had brought about high unemployment and emigration from the country.

Photographs by Lidwien van de Ven zoom into the hidden details of notorious public political events, implicating the viewer in their content. Since 2012, the artist has been capturing the complex dynamic between the revolutionary pulses of social transformation and the counterrevolutionary resurgence in Egypt. Depicting the contested period of the Egyptian political uprising through visual fragments, van de Ven portrays the oscillations of the very subject of the revolution.

Since the mid-1970s, Mladen Stilinović has been developing artistic strategies that combine words and images, using “poor” materials to engage the subjects of pain, poverty, death, power, discipline, and the language of repression. His pamphlet-like, agit-poetic works offer laconic commentary on the absurdity and crudity of power relations and the influence of ideology in contemporary life.

Another way to think of effect of images as directly useful is of course related to political propaganda, the role they might have in arousing to political action, probably most directly present in the works Emory Douglas created for The Black Panther, the newspaper of the Black Panther Party published during their struggle against racial oppression in the 1960s and 1970s in the United States. But tapestries of Norwegian artist Hannah Ryggen, made in the 1930s with motives related to the rise of Fascism, Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia or Spanish Civil War, could also be read as propaganda, in the original meaning of the word propaganda, which can be defined as “things that must be disseminated.”

But, next to these functions of images related to politics through its subject matter, aiming at raising consciousness, calling to political action or partaking in the formation of political or revolutionary subjectivities, there is an understanding running through the exhibition that is perhaps best exemplified by Partisan Art, and that is that it is not the role of art to change the world, that this is the task of political struggles, but of course art participates in this change. The exhibition presents the selection of different materials related to Partisan struggle in the World War 2 in Yugoslavia struggle which was not only fight against fascism, but also a social revolution, and also a cultural revolution, where masses of anonymous partisans became cultural workers, poets, performers. But what makes these works partisan art is not any specific formal language, but participation in the struggle.

It looks into effectiveness, efficacy, vitality and potentiality of images, as expressed in forms of community art and popular art, like, for example, in the work of Russian artist Viktoria Lomasco, who has developed Drawing Lesson (2010), a project in which, as a volunteer for the Center for Prison Reform, she has been giving drawing lessons to the inmates of juvenile prisons in Russia. Lomasko developed her own methodology of empowering the socially oppressed by employing images to strengthen analytical thinking and empathy.

Also in Ardmore Ceramic Art Studio, collective from South Africa who made ceramics as response to official government silence on AIDS, or in paintings by Primitivo Evanan Poma and Association of Popular Artists of Sarhua, that uses the traditional pictorial style of the Sarhua region in Peruvian Andes to depict subjects related to life of indigenous people forced to immigrate to Lima. These works, like many other, collapse the division between high and low art, division embedded in the Western canon and its place within colonial histories.

The exhibition also argues for uselessness of art and how useful its uselessness actually is today, when instrumentalization of knowledge within reductive utilitarianism measured primarily by economic profitability reduces knowledge, imagination and of course public education into tools of social reproduction.

The tensions and contradictions pertaining to the possibility of reconciling high art and political militancy figure also in Carla Zaccagnini’s Elements of Beauty (2014), a project that examines protest attacks on paintings in UK museums carried out by suffragettes in the early twentieth century. By outlining the knife slashes made on the paintings, Zaccagnini retraces them as abstract forms, while the accompanying audio guides provide fragmented information on the suffragettes’ court trials. One hundred years after those iconoclastic attacks, Zaccagnini’s work poses uncomfortable questions about where we would put our sympathies and loyalties today and how we know when we have to choose.

Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge’s series of photographs Art Is Political (1975) employs stage photography to relate social movements with a field of art. The series combines dancers’ bodies in movement with Yvonne Rainer’s choreography and Chinese agitprop iconography, with each photograph composing one lett er of the sentence “Art Is Political.” Finally, the project Degenerated Political Art, Ethical Protocol (2014) by Núria Güell and Levi Orta uses the financial and symbolic infrastructure of art to establish a company in a tax haven. With help from financial advisors, the newly established “Orta & Güell Contemporary Art S.A” is able to evade taxes on its profits. The company will be donated to a local activist group as a tool for establishing a more autonomous financial system, thus using the contradictory mechanisms of financial capitalism as tools in the struggle against the very system those tools were designed to support.