In the 1975 novel Les météores by Michel Tournier, one of the main characters, Alexandre Surin, worships refuse, managing the dumps of several major cities. “To me, it is a world parallel to the other, a mirror reflecting what is the very essence of society, and a variable but entirely positive value is attached to every bit of muck,” the author has his character say. While he optimizes the refuse, which varies significantly from one city to another, he respects those who seek to restore its lost dignity. No doubt he would have appreciated Tender Debris, which brings together twenty two artists who share the common trait of making art with what they have on hand or find in the trash. In other words, with Everything that remains — the title of a previous gallery exhibition dedicated to Arman, a member of the Nouveau Réalisme movement, which made the reappropriation of ordinary debris a central practice. Tender Debris brings together a selection of works from 1959 to 2025, made from what dumps overflow with, what litters the sidewalks and fills flea markets, what the sea casts on the shores, whatever remains after being produced, used, and consumed. It highlights what we usually prefer to forget, by celebrating a practice and an art of recycling with diverse origins and aims.

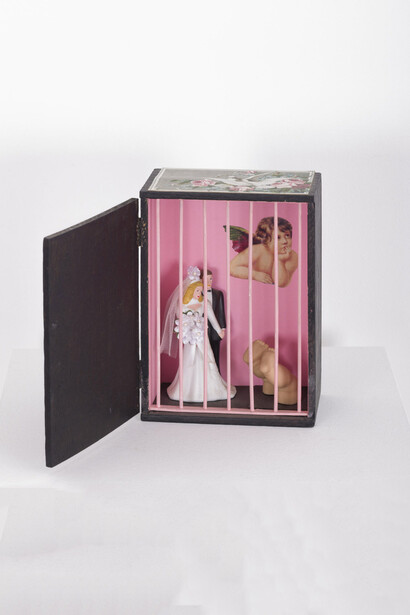

While some artists engage with refuse by aesthetic or political choice, pointing to overconsumption, obsolescence, and the absurdity of a world organizing its own loss, others use it out of necessity, bearing witness to a certain economy of creation. All of them come together in their ability to transform waste into poetic fiction, giving it new value. Arman logically figures among the exhibited artists, with a New York-era trashcan filled with waste drowned in resin. Alongside him, Niki de Saint Phalle is represented by a large dragon made from an assemblage of cheap materials and toys that belonged to her children; Jean Tinguely contributes with two contraptions, one made of rusty metal, old light bulbs, and colorful feathers, the other with a stuffed wild boar's head; Jacques Villeglé, François Dufrêne, and Raymond Hains show a series of torn posters. This “poetic recycling of reality,” which characterizes the approach of the Nouveau Réalistes, is found in the works of their American contemporaries George Herms, who transforms relics into objects that are once again desirable.

More recently, Henrique Oliveira transforms the humble wood of construction barriers salvaged from Brazilian favelas into colorful sculpture-paintings. Martin Kersels gives a second, joyful life to old objects, furniture, and reclaimed wood. In a different register, Julien Berthier celebrates reality by replicating, in painted aluminum sculpture form, the shapes created by bulky waste left on the streets of Paris, which he then places on a solid wood pedestal, conferring on them their definitive status as works of art - whereas the young graduate of the Beaux-Arts in Paris, Emmanuel Van der Elst, creates imposing yet precarious architectures by assembling, without fixing, leftover picture rails and office furniture.

Plastic, another reigning refuse (produced, consumed, and discarded en masse), gently pollutes the exhibition, sometimes in deceptive forms: artificial geranium bouquets displayed in old tin cans by Pilar Albarracin, repurposed dolls by Tomi Ungerer, and trompe-l'œil flowers by William Amor, fake scrimshaw and real cans salvaged from beaches by Duke Riley - the other debris collected by the American artist serving to create works where seashells and plastic waste are once again brought together, for eternity.

The artist Moffat Takadiwa, based in Harare, one of Zimbabwe's largest recycling and informal economy centers, also finds a new and noble use for toothbrush heads and keyboard keys found in vast quantities in local dumps, creating large-scale wall sculptures with unexpected preciousness.

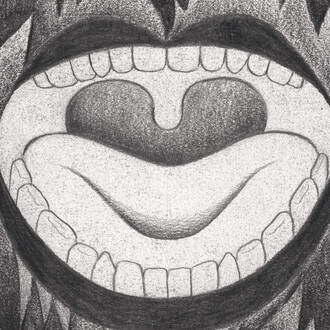

The cigarette butt also becomes a resource, used by the Beninese artist and former fashion designer Prince Toffa to create a gown with an imperial look. Others, such as Perrine Guyonnet and Winshluss, “play” by immortalizing what remains or will remain through photography and drawing. For English artist Ryan Gander, the answer might lie in the sculpture that represents him - an avatar of rags resting on a large, plush garbage bag, likely filled with tender debris.

(Text by Barbara Soyer)

![Mohsin Taasha Tappa-e Shuhada Roshnaaie [Hill of martyrs of enlightenment] from Rebirth of the Reds series, 2022. Courtesy of Galerie Eric Mouchet](http://media.meer.com/attachments/88a9b99d56257bd44c1e6e68377f280e3350a066/store/fill/330/330/e9d8f49d377be692a716e38249550040d715c57af996eabbdb47f1967679/Mohsin-Taasha-Tappa-e-Shuhada-Roshnaaie-Hill-of-martyrs-of-enlightenment-from-Rebirth-of-the.jpg)