Bel Ami and CW American Modernism are pleased to present the first retrospective devoted to the work of New York-based artist Marina Stern (b. 1928) since her passing in 2017. Luminary sheds new light on the practice of an artist who responded to her times in different formal modes, but always with her own insight. With a deft, nearly imperceptible brush stroke, Stern painted modern spaces that merge concise observation and invention, prompting reflection on the artifice of representation. In a dynamic career that spanned fifty years, Stern contributed to Pop and Op Art movements, and later, to the revival of American Precisionist architectural and still life painting. Although her subject matter varied as she painted through the decades of a colorful century, Stern infused all her compositions with a unique drama by training her attention on light.

In this two-part exhibition, Bel Ami displays a selection of whimsically surreal paintings from the 1960s, as well Stern’s later still lifes. CW American Modernism presents Stern’s well-known cityscapes, industrial sites and barns.

A native of Venice, Italy, Stern and her family fled to escape repressive racial laws against Jews in 1939. After living in England for several years, they arrived in the United States in 1941. In New York, Stern studied advertising design at Pratt. After graduating at 18, she pursued a career in commercial illustration, while at the same time continuing to paint. In the 1960s she began exhibiting in East Coast galleries and institutions. With a sharp eye and a playful wit, Stern took advantage of her exposure to European and American art to cultivate her own slant on trends and tropes.

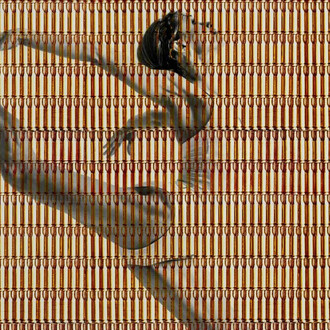

Stern’s early works, often with warping checkerboard patterns and mirroring effects, played on old and new perspectives by appropriating figures from Renaissance paintings and positioning them inside surreal dreamscapes. The hexagonal painting Nocturne (1966) features an illuminated portal at its center, with court musicians mocking the drama of the composition. Renaissance (1969) frames a receding sequence of windows, referencing Josef Albers’ Homage to the square (1950-1976). The elegant symmetry is interrupted by another classical motif, presented in repetition: a Portrait of a lady (c. 1485) by Sandro Botticelli copied four times. Bull and bear (1967) coyly stages symbolic figures from the stock market in a geometric space that seems outside of any real place or time. In reference to an exhibition of Stern’s Op Art paintings of the 1960s, a critic at The Boston globe wrote: “she seems to be having fun. And you will too.”

Other works from this period incorporated sound. For example, in Hay day (1964), exhibited at New York’s Amel Gallery, Stern depicted a small copy of Francisco Goya’s La maja desnuda (1797–1800) lounging along a high horizon line with a real drawstring inserted through the canvas. When pulled, a voice mechanism—scavenged from one of her daughter’s dolls—asked, “Will you play with me?” Time magazine called her audio-visual pieces the “cleverest noisemakers” in the exhibition. Her compositions, with their wry and oblique comments on creative artifice, earned her acclaim, and a place in the exhibition The new American realism (1965) at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts, alongside leading contemporaries such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Marisol Escobar, Robert Raushenberg, and Jasper Johns.

Over the course of the next two decades, Stern created large harmonious paintings featuring carefully composed flowers, fruits, and vegetables, often set against the backdrop of her New York studio. Though they contrast with the more stylized paintings, these works reveal a through line in Stern’s artistic practice: her compulsion to turn the canvas into a mysterious portal, while also playfully addressing her own mimetic subterfuge. Her hyperreal still lifes, on view at Bel Ami, are bathed in perfectly balanced light, yet the objects seem to occupy a metaphysical space. The self-referential Interior with cabbage (1979) features the purple vegetable rendered whole, and a drawing of the same vegetable—now bisected—pinned to the crossbar of a stretched painting (a version of the cabbage drawing appears in Stern’s 1978 cookbook, A book of vegetables: recipes and drawings). Also on display at Bel Ami are Still life with lily, red tulips, and red pears, all painted in 1987. By the 1990s and early 2000s, Stern’s still life compositions became more stark and almost exclusively focused on subjects that accentuated the interplay of light and shadow. The culmination of this concern was a series of more than fifty paintings of paper bags, folded, crunched, twisted and otherwise manipulated under a harsh light. Two of the most significant remaining uncollected paintings from this series are featured in this exhibition.

Concurrent with the still lifes, Stern began to paint industrial scenes and landscapes. Her pristine renderings of light falling upon urban and rural America are clearly grounded in observation, and yet they also read as pictures in the mind’s eye. These New York cityscapes, granaries, barns, and bridges are on display at CW American Modernism. However, some of Stern’s most inspired cityscapes respond to the time she spent as an adult in Italy, where she captured the unique glow of Venetian light in her depictions of the famous and quotidian. In Street lamp (1988) a modern junction box and projecting electric lantern intervenes upon a distant view of the Basilica di Santa Maria della Salute. Malamocco (1989) centers the bell tower of the church of Santa Maria Assunta, as seen from the village square; the empty street foregrounded by a red wall cast in shadow resembles Surreal and enigmatic piazzas painted by Giorgio De Chirico (1914-1915). Stern’s works are precise but not realist: the stripped down visions are free from dirt, grime and other messy details, and yet suffused with light. Stern, with virtuoso skill, was not seeking absolute verisimilitude. Rather, she created a beautifully designed alternate reality, editing and essentializing her surroundings.

Refusing to conform to just one style and subject, Marina Stern followed her own vision, transforming her study of modernity into striking compositions. During her lifetime, Stern’s work resonated with a wide audience. Her exhibitions at galleries and institutions were reviewed in major publications, and reproductions of her images were used to illustrate mainstream magazines. Her paintings were acquired by illustrious private collectors including Harry Belafonte and Jackie Kennedy. Today, her work is included in the collections of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the National Portrait Gallery, the Smithsonian Institute, The Museum of Modern Art, the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University, and the Gibbes Museum of Art.

Marina Stern: Luminary is made possible by CW American Modernism, and is part of an ongoing project to honor successful women artists who have been overlooked in the documentation and historicization of art. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue—available at the gallery—with an essay on Stern’s life and work by Chris Walther, founder of CW American Modernism.