With her third solo show at Semiose gallery, Aneta Kajzer maintains a cycle where each exhibition appears to emerge from the previous one as a natural mutation of her universe. Heavy water, staged in 2021 represented the first installment, with its dense, fluid paintings rippling with currents and internal eddies. Two years later, Head in the clouds ascended towards lighter skies and featured suspended forms and faces floating amidst the color. In Too close to the sun this trajectory is set ablaze, pursuing a radiant apotheosis, appearing as an almost mythical ascent. After water and air, fire takes their place: In the same way as Icarus, the painting ascends to a point of almost dazzling luminosity, fully conscious of the risk of losing its form, yet also aware of the exhilarating freedom that accompanies this proximity to the sun. What was once flowing and evaporating, condenses in radiant heat: the matter reaches its fusion point where light becomes color and color becomes energy.

Aneta Kajzer’s sun is not an astral body: It is a flood of paint, a furnace that dilates and dissolves forms, bathing them in burning color as if, when brought close to their flash-point, these colors might gain an extra degree of freedom. In some cases, this chromatic stridency attains an almost electric intensity: the acidic pinks, the lemon yellows and fluorescent greens generating their own light and the energy-saturated surfaces becoming sun screens. These areas of over-exposure provoke dissonance, summoning a collision of contrasts that quiver to the point of irreconcilability and stretch harmony to the brink of rupture. In these almost overly-luminous instances, it is as if Aneta Kajzer were exploring a territory where painting is accomplished at the risk of being scorched in order to achieve more clarity. Too close to the sun lays bare that precise instant when painting takes the form of a kind of unstable meteorology, a critical point beyond which wind-swept brushstrokes, downpours of pigments, flashes of red-orange oxidation, misty pastels and cool, shadowy layers are unable to hold their place in the atmosphere and are condemned to an inexorable fall.

Nothing is planned in advance: forms emerge in the painterly flow, guided by interactions between materials, by the fragile balance between the painter’s gestures and the withdrawal of her brush. Aneta Kajzer’s painting is comprised of vigilance and attention, a practice that lies in wait for its own revelations. Her figures never appear due to premeditated decisions, but as slowly formed apparitions, born of the climate of each work. They emerge from the colors as if from a nebulous haze, a stroke of controlled luck, a run interrupted at just the right moment, a smear that suddenly acquires meaning in a melancholic flurry, or on the contrary, in a slightly insolent or humorous pirouette. The various figures can be sensed before being fully recognized, like a face glimpsed in a cloud or reflected in water; discovered rather than invented. In the same way as when a cloud-watcher perceives a head, a profile or an animal, the artist hunts down fleeting resemblances and lets pareidolia reveal the scene: a brush-stroke, a swollen drop or a metallic scratch etched with the edge of the paint-tube might all contribute to the sketching out of the outline of a face, then, in the instant that follows, vanish into the abstraction of an evanescent figure.

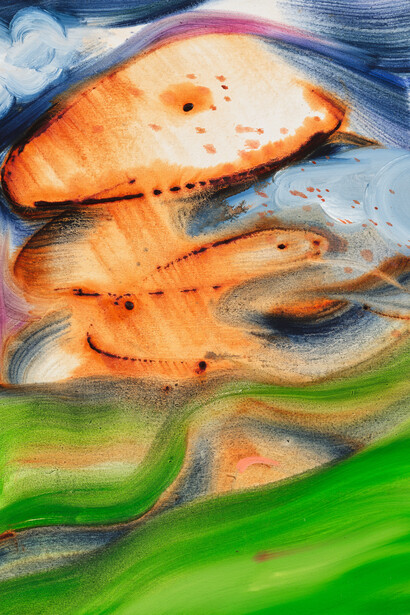

In the painting Doppelgänger, the mass of ultramarine blue transforms into hair, a child’s, smiley-like face is overshadowed by a second, almost menacing figure, composed of a broad purple stroke curving through the space of the canvas and whose eye / dot reveals a divided being: two faces, two approaches (drawing / painting) coexisting like two simultaneous moods. In Harvest, a small, faintly smiling orange landscape-cum-face, covered in spots, is bathed in a midnight-blue breeze; the pastoral green opens up into a liquid hillside. The pareidolia is frank and intentional, nature takes on a form which itself then resolves back into nature, in an analogy with certain nuagiste paintings by Jean Messagier.

The sheer pleasure taken in painting is evident through its almost ecstatic intensity and in the interplay of differing textures and viscosities—diluted or velvety oils, more turbulent watercolors—in the streaks that become hair or wind. Each gesture starts out as a tactile or chemical event before taking form as a contour sustained by its lightness and capacity to signify and then withdraw—to create a figure and almost immediately return to pure matter. The painting Slippery slope is one of the most explicit examples of this shift, with its flowing orchid pinks, its suspended deep blue, the pale yellows that seem to evaporate from the surface and a violet inflection that barely hints at a profile. The painting does not simply advance toward the viewer, it cascades downwards, its adherence shifting through an accumulation of frictions.

What might appear can also rapidly retract, catch its breath and move on. This feathery lightness does not exclude storms: in Aus dem paradies vertrieben (Expelled from paradise), the deep purple mixed with rusty brown announces the oncoming turbulence; blood reds and mauves knot together to form tunnels; violets contort into organic passageways; a pink bulb opens out, undecided whether it’s an inner sun or a puffed-out cheek; the representation itself pulses and retracts as if the motif had been expelled from itself by its own inner currents. Aneta Kajzer’s more recent works find their focus in a rusty oxidized palette reminiscent of corroded metal that has been left exposed too long, as well as contrasting bright pastels (acid yellow, milky blue and powder pink): When they get too close to the sun, the colors intensify and become almost caramelized, finally clarifying into a mist of light.

Venturing too close, taking the risk of being incinerated, is the natural fate of paintings where accidents are a veritable aspect of the painter’s methodology, where the unexpected is a given, where the works are born at their inception, without preparatory sketching, through reversals, erasures and fresh beginnings. In places the colors detach themselves from any tonal nuance to reach a state of pure intensity that surpasses stridency or any scorched effect to attain an absolute clarity of a tone that asserts itself alone: Pure pink, true blue or yellow verging on the immaterial. These flat tints, with their almost naïve clarity open up clearings in the density of the canvas; they function as optical breathing spaces, areas where the tumult of the painting seems to be suspended, in order for it to view its own existence.

(Text by Jean-Charles Vergne)