Galerie Chantal Crousel is pleased to present Partituras, a new exhibition by Gabriel Orozco, featuring a selection of recent works on paper and paintings created between Paris, Tokyo, and Mexico City.

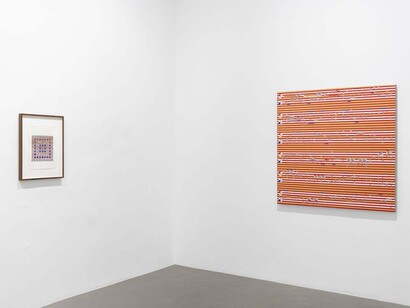

This body of work deepens Orozco’s exploration of rhythm and abstraction through a process where music becomes method, structuring each composition. The Partituras unfold gradually: from improvisation to recording, then drawing, and finally painting. Titled with the location, date and time each melody was recorded on the piano, the works hold a quiet code, where sound is translated into shape and colour.

Art historian Briony Fer observes, “there’s something deliberately out of sync—even improbable—about the way Gabriel Orozco’s new paintings recall abstraction’s original alliance with music—one clearly articulated by painters like Kandinsky and Kupka who were both interested in the sound of colour and the possibilities of chromatic vibration in painting.”

This tension between structure and intuition is at the core of Partituras. The project begins not in the studio, but at the keyboard. Fer explains: “This is a part of the process Gabriel Orozco associates with particular feelings as he ‘draws’ with his hands on the keys. When he played the piano for this project, he recorded his improvisations, usually lasting only a few minutes; the recordings were then sent to a professional musician to be transcribed and printed as a piano score. Each short piece that he makes was rendered in this way, with the notes distributed across the five horizontal lines of the stave—pentagram—according to the traditions of musical notation. Next, the score was translated into a diagrammatic drawing and only then into a painting. Based on the system Orozco has created using the four colours—red, white, blue, gold—each painting corresponds to a particular piece of music, but has been highly mediated and transformed along the way.”

These are not literal transcriptions nor traditional notations, but layered structures where gesture and colour resonate together. Partituras also gestures toward broader, more complex histories of abstraction. Briony Fer notes how the project reactivates not only the spiritual affinities between music and painting but also their more critical and transgressive intersections: “There’s a certain symmetry in the way Barthes describes sitting and playing the piano as the most ‘muscular, manual’ part of music and the way Orozco likens playing to drawing, which is arguably also the most ‘manual’ part of art.”

Drawings punctuate the project. They are made “independently of the process as ‘fictions’ because they do not have a one-to-one relation to the sound or melody of his piano pieces. They are more improvisatory, detached from the stricter rules of codification of the paintings.”

In several works, circles, standing in for musical notes, appear as miniaturised constellations, suspended between the five lines of the stave. Briony Fer describes them as: “a mise en abyme, where familiar elements within his geometric language are dispersed across and ‘float’ in the spaces between the lines [...] driven by the horizontal lines of the pentagram – or what Orozco neatly calls the ‘linear horizon’. The bands of colour invoke textiles and thread, rather than revolving circuits. Paradoxically, despite what might be seen as a surfeit of intricacy filling the pictorial surface, they interrogate very basic semiotic questions about how to make paintings at a time when that seems a very improbable question to be asking. […] As paintings, then, they are unpredictable and entirely susceptible to their surroundings and the passing of time.”

In Partituras, drawing, music, and painting come together as parallel languages, tactile, temporal, and speculative. Each work becomes a surface where a sound once occurred, and where it might, once again, be imagined.