Deborah Brown’s recent still life paintings are based on objects in the artist’s collection, treasured mementos gathered over the years and displayed in her domestic environment. Like Proust’s famous madeleine, the artist’s figurines, furniture, and crockery become a vehicle for conjuring her past.

Brown’s still life paintings function like portraits, revealing the life of the artist and serving as a gateway to her thoughts and feelings. The paintings are constructed with strong blocks of color, which create a feeling or an emotion rather than a realistic depiction of a specific environment. The work of Henri Matisse, Lovis Corinth, and Gabrielle Münter are all important influences that Brown draws on in her construction of the paintings. Through the action of paint and brushwork, the objects come alive and assume a mysterious character, perhaps as emissaries to another world.

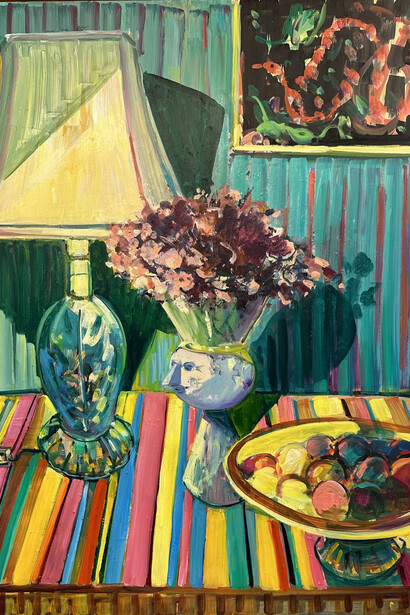

The objects in the work come from different parts of the artist’s life, reflecting her affinities and fascination with other cultures. Several of the paintings feature Kachina dolls made by members of the Hopi Indian tribe in America’s Southwest. Brown purchased these totems when she was in elementary school, and they retain the power and mystery they held for her as a child, qualities she channels in her paintings. Another character repeated in the work is a large Japanese silk screen depicting peacocks and flowers. Brown’s parents traveled throughout Southeast Asia in the 60s, and this screen was a strong visual element in her childhood. The artist also inherited furniture and decorative objects from her mother’s travels to Copenhagen in the 1950s, including works by designers such as Arne Jacobsen and Finn Juhl. Foremost among these are ceramic “face vases” by Bjoern Wiinblad, which appear prominently in the paintings. Brown places the vases on a Mexican woven-cloth “saltillo,” a nod to the artist’s childhood in Los Angeles, where Latino culture is a constant presence. The vases represent the artist who organizes the elements in the painting according to her vision and affinities. Lastly, the artist depicts skulls assembled during her husband’s study in dental school. The skulls reference the Vanitas tradition of memento mori painting, in which earthly pleasures are depicted as symbolic of the inevitability of death and the transience and vanity of material pleasures.

Each of us defines our world by a selection of the objects we choose to surround ourselves with. By depicting a highly personal space, the artist strives to create a connection to the viewers, who brings their own relationship to domestic interiors and engage with the broader notion of what it means to be human through an artist’s vision.