In Maria Wæhrens’ loose, almost sketch- like painting Queer baby, a small human figure stands in the middle of a landscape. It is quickly rendered in blue, almost translucent brushstrokes, surrounded by wild swirls of a pink hue. The painting’s palette is limited, consisting mainly of pink and oxblood red, with touches of blue and a light, airy ochre yellow. The red tones of the landscape evoke flesh and skin, while the blue figure’s corporeality appears more uncertain. On one hand, its body language and mischievous smile signal a presence; on the other, the figure is transparent, almost ethereal - as if it allows the surrounding world to blow straight through it, and is perhaps only just in the process of becoming.

The relationship between body and spirit plays a central role in Maria Wæhrens’ expressive and existentially charged paintings. More broadly, one might say that Wæhrens’ work often revolves around the tension between something (almost unbearably) concrete on one side, and something more intangible on the other. The paintings in the current solo exhibition Heaven at Wilson Saplana Gallery explore, drawing on the artist’s dreams and spiritual experiences, a series of intersections between the erotic and the spiritual; between desire and suffering, body and the subconscious. At the same time, Wæhrens draws upon a cast of characters that can often be traced through the works’ titles.

Maria Wæhrens has always tuned into energies and attitudes through people from her life, as well as through figures - particularly from Christian mythology. They serve as kinds of muses, invoked during the painting process so that their spirits and presence might influence the direction a painting takes. In some works, they are only there in spirit; in others, they enter directly into the motifs, as in Bente and the doctor and No one and see you in heaven faster Maria. Zadkiel, part of a series of paintings named after Christianity’s archangels, is based on a dream in which an outcast figure from the artist’s family history appears as a helpful messenger.

Wæhrens’ upbringing in a Christian environment has inscribed itself into her body, and traces of the Christian visual tradition seep into her paintings, lending them an ambivalent stroke of both mirroring and resistance toward archetypal religious imagery. It is a relationship Wæhrens continues to negotiate - bending and turning it in new directions. The interplay between light and darkness is also central. In some of her earlier works, dark and dense in tone, fluorescent tubes painted into the motifs cast a cold, overhead light on the figures - almost a parody of divine illumination. A similar duality is found in the light of the paintings in Heaven, shifting between a white, seemingly earthly light and a golden one that gestures toward the spiritual. In places, her brushwork evokes the luminous rhetoric familiar from the Baroque and the Catholic church.

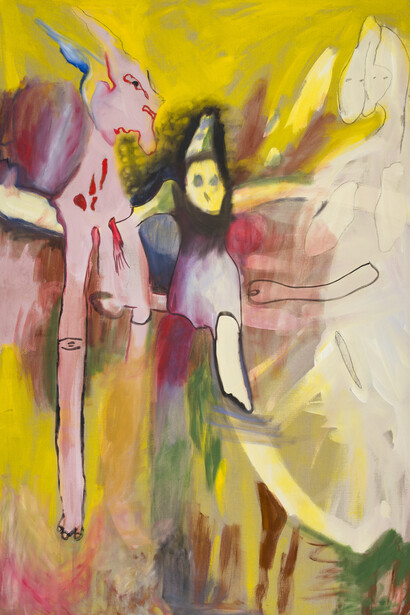

In the five paintings from the series See you in heaven, the light oscillates between the sacred and the profane, placing the scenes in a kind of limbo. This series, too, stems from a dream that Wæhrens revisits almost ritually across five iterations. The title is a tribute to an older family member, the artist’s outspoken namesake, Aunt Maria. “See you in heaven” was a phrase she would often say when parting during Wæhrens’ childhood. The dream involves a movement from room to room - and, more specifically, the experience of having a penis. An extra body part imbued with potential and usable energy. The recurring central motif sketches a sex scene that takes on various expressions, moving from the tender to what - tinged with a comic-strip quality - resembles a kind of cosmic fistfight. Some of the works in the series recall the Baroque sculptor Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini’s famous Ecstasy of Saint Teresa in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. Here, too, one finds an explicit example of the link between religious and sexual ecstasy - an unspoken aspect of much ecclesiastical art, one that gestures toward suffering and shame while reminding us of which forms of ecstasy are deemed the truest and purest.

Wæhrens’ semi-abstract paintings speak from personal experience. At the same time, their expressive visual language carries an inheritance from the avant- gardes and from the centuries-old method of automatism. The tradition of expressive painting bears an urge toward documenting something raw and authentic - to create an external, tangible proof of something inner or invisible - even though the works, of course, involve acts of construction.

From a queer perspective, as in Wæhrens’ case, an expressive painterly language may feel like an obvious means of reaching out when living in a society or environment that tends to cast doubt on the authenticity - or even the very legitimacy - of one’s lived reality. The need to be believed and mirrored is universal. The philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt has, in another setting, described how the opposite can lead to a shadowy existence: “For human beings, reality is constituted through appearance, that is, when something can be seen and heard both by others and by ourselves... The presence of others, who see and hear the same as we do, gives us assurance of our own and the world’s reality” (The Human Condition, 1958). The exhibition Heaven can also be seen in this light.

(The exhibition text is written by Maja Gro Gundersen)