Charim Galerie presents a significant selection of works by Ulay, shown in parallel with the exhibition Marina Abramović at Albertina Modern. The aim of this exhibition is not only to showcase Ulay’s artistic oeuvre but also to convey and make comprehensible his unique artistic stance. Through access to archives in Ljubljana and Amsterdam, we have been able to include original working documents and archival materials that form an essential part of the show. Ulay’s life and work will also be explored in accompanying events, allowing for a deeper engagement. In this context, Ulay at Charim Galerie is part of a broader curatorial narrative that also points toward the upcoming museum exhibition “Art Vital – 12 years of Ulay / Marina Abramović at Cukrarna in Ljubljana, curated by Alenka Gregorič and Felicitas Thun-Hohenstein.

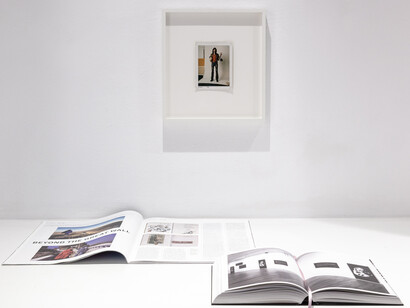

We first encounter Ulay at the entrance to Charim Galerie as a young man staging himself in front of the camera—and making this staging visible. A white backdrop has been set up; to its left, parts of a studio can be seen, along with the attributes of 1970s youth culture: long hair, a flamboyant jacket, embroidered jeans with boot-like leather gaiters sewn on. This Polaroid, a self-portrait from 1970, already brings together essential elements that would later define Ulay’s life and work. His deliberate act of showing is most clearly manifested in two objects he holds: a Polaroid instant camera—his tool of the trade, as he worked for the Polaroid company—and a life-size mask of a neatly groomed boy, representing the very opposite of what preoccupied him in Amsterdam in 1970.

Ulay was born Frank Uwe Laysiepen in 1943 in Solingen, Germany. After a childhood spent amidst the ruins of World War II, he became an industrial photographer with his own studio and started a family. He left his wife and son to avoid conscription into the German army. In the late 1960s, he first traveled to Prague and then settled in Amsterdam. In this new life, the mask of post-war German normality became an identity marker he had discarded.

Amsterdam offered Ulay a stimulating environment, one that encouraged the testing and crossing of boundaries through self-experimentation. He moved through various scenes, including anarchist protest circles (Provos), known for their satirical actions that later influenced extra-parliamentary opposition movements. He engaged with homelessness, the squatter scene, documented the lives of transsexual and transgender people, and met Jürgen Klauke, who shared similar concerns. He later became part of the founding environment of De appel (1975), a new-format art institution that provided a framework for emerging body and performance art. It was here that a young artist from the former Yugoslavia, Marina Abramović, would meet the Ulay she so admired.

Initially, Ulay experimented with the Polaroid camera, which allowed for intimate, boundary-pushing self-exploration. These early works were not originally intended as art but as personal investigations of the self and others. Over time, this self-inquiry evolved into a performative artistic practice of identity exploration in front of the camera.

Our intuitive understanding of identity formation assumes that we exist in a temporal continuum, interpreting our life story—and by extension, our artistic activity—as an expression of personal identity. But Ulay moved at the margins of society, where it became clear that many life stories do not follow coherent narratives. It is precisely this instability that calls into question the illusion of normality and the societal norms, exclusions, and role expectations that sustain it. Through his performances and staged photographs, Ulay transformed his body into an image—into an “Other”—and began to see himself as an object. He portrayed himself in a gender-fluid manner, developing a synthesis of “he” and “she”, which he also embodied in public, with one side of his face made up and feminine, the other stubbled and masculine.

His art expresses this process of recognition and simultaneously alters it. The interplay between the self-perceived and the Other of his own body creates a dynamic that becomes productive for his later work. He explored his body to the point of self-injury, using artistic means to ask: what kind of self emerges from this understanding?

He created identity collages (Renaissance Aphorism, 1972–75) from close-ups of various body parts, their “anagrammatic” composition reminiscent of works by Valie Export. He confronted the lingering effects of trauma (Traumatic Fears, 1973), and his self-portrait lying in bed, perhaps alludes to Hitler’s favorite painting, The Poor Poet—a bitter irony given the short-lived reign of the so-called Thousand-Year Reich and its traumatic legacy for generations. Life could no longer be romanticized; the façades of bourgeois normality had crumbled.

This radicalized self-exploration became a voice for a youth in upheaval, striving for social change and embracing utopias whose political momentum made many of today’s freedoms possible. Ulay was in the thick of it (Death of a transvestite, 1973). His work Metamorphosis of a canal house (1972) was one of his “visual and ecological interventions,” offering direct insight into the art scene of that time, supported in this exhibition by numerous archival documents from the period.

The artistic environment of De Appel played a central role. The presence and performances of numerous artists helped define “Body Art” and “Performance Art” as a newly emerging field. Artists discovered each other’s work and forged connections—some lasting, others leading to lifelong rivalries. Ulay actively participated, performing with Jürgen Klauke, meeting Laurie Anderson, James Lee Byars, Gina Pane, Chris Burden, Ulrike Rosenbach, and Marina Abramović, who took part in his performance Phototot.

Eventually, Ulay let go of the idea of a singular personality, a shift he marked in 1974 with a death notice: “My farewell as a single person / 1943–1974”, which forms a conceptual anchor in the first room of our exhibition.

Ulay’s ever-reflexive use of media—his own body, photography, and performance in front of an audience—culminated in a kind of self-erasure of the photographic image itself. In the Fototot series, the photograph vanishes into opacity under the viewer’s gaze, becoming a black, impenetrable surface. The legendary period he shared with Marina Abramović, under the motto Art Vital, followed this and gave concrete meaning to the relationship between art and life— by asking what consequences such an understanding of art has for life, not the other way around. This means crossing boundaries in and through art, taking risks, being vulnerable, and for Ulay, living an ethic expressed in his credo: “Aesthetics without ethics is cosmetics.”

This exhibition seeks, through selected works and archival material, to affirm the significance of Ulay’s early oeuvre, and to show how these themes and practices deeply informed the joint performances with Marina Abramović. Their legendary collaboration is the subject of the exhibition Art Vital – 12 years of Ulay / Marina Abramović, which our show points toward.

The final room of the exhibition refers to the period after the couple’s separation and offers a preview of future projects at our gallery, which will deal with this later phase of Ulay’s work. He continued to focus on marginalized communities, with political and social engagement remaining central to his practice. As in his early years, he was concerned with the fluid transitions between art and life, the dissolution of identity, and subversive strategies that also questioned the commodified art market. He returned to photography, as powerfully shown by the three monumental Polaroids from Black Skull (from the series Can’t beat the feeling – Long Playing Record), 1992.

In contrast to the visual dominance of the Black skulls, we present Unhurt (Relation in space), 2015— a work that reflects Ulay’s vulnerability, which inherently involves the risk of crossing boundaries. He remained concerned with the limits of photography as a medium and the ongoing question of art’s impact on life.