Thaddaeus Ropac Salzburg presents an exhibition of new works by Austrian artist Markus Schinwald. Large-scale tapestries and an immersive soundscape, that hovers on the limits of perception, will envelop the gallery space, transforming the rooms of Villa Kast into a uniquely experiential setting for Schinwald’s recent series of paintings. The works suggest a conversation between the past and the future, sparked by an analogue method that bridges centuries of artistic and conceptual thinking.

Having explored the complexities of inhabiting and perceiving the body for many years, Schinwald’s recent work investigates the deformation and decline of ‘memory culture’. For the artist, this not only includes retrospective constructions of the past, but also speculative imaginings of the future – as seen, for instance, in science fiction films – which are inevitably built from fragments of our past. Schinwald is particularly interested in the ‘flattening’ and self-referentiality of images and sound fostered by artificial intelligence and algorithm-driven media. For this exhibition, the artist seeks to ‘create a specific sense of space or interior,’ while employing ‘various methods of resurrection, ranging from restoration to generative technology.’

The tapestries created for this exhibition reflect the composite nature of the artworks. While some were generated using AI and depict ravaged interiors reminiscent of disaster scenes in Hollywood films, others are based on a fresco by Renaissance painter Giotto di Bondone, which Schinwald altered digitally. The architectural elements in Giotto’s cityscape never existed in real life but rather show a constructed reality – now arranged in a seemingly endlessly expandable row in Schinwald’s tapestries. The edited image still appears somewhat historical to the viewer, but can no longer be precisely placed or dated, creating a kind of time warp. With looms being the first programmable machines controlled by punch cards containing the information of a pattern in the form of binary code, the medium of tapestry carries multi-layered historical meaning as a precursor to today’s digital language. The concern that human labour might become obsolete – a question that resonates strongly today – was central to the introduction of mechanical looms in the early 18th century. The machines reduced the need for skilled handweavers, driving down wages, causing unemployment and sparking unrest.

Fascinated with the concept of the ‘holodeck’, a fictional device from the television series Star trek, which offers the user interactive simulations of specific rooms or locations at the touch of a button, the artist sought to create the sense of a constructed universe within the gallery space. This impression of entering a virtual space, similar to that of a video game, is further enhanced by the hardly audible layer of sound, that brings about the feeling of a distant space without any determinable origin.

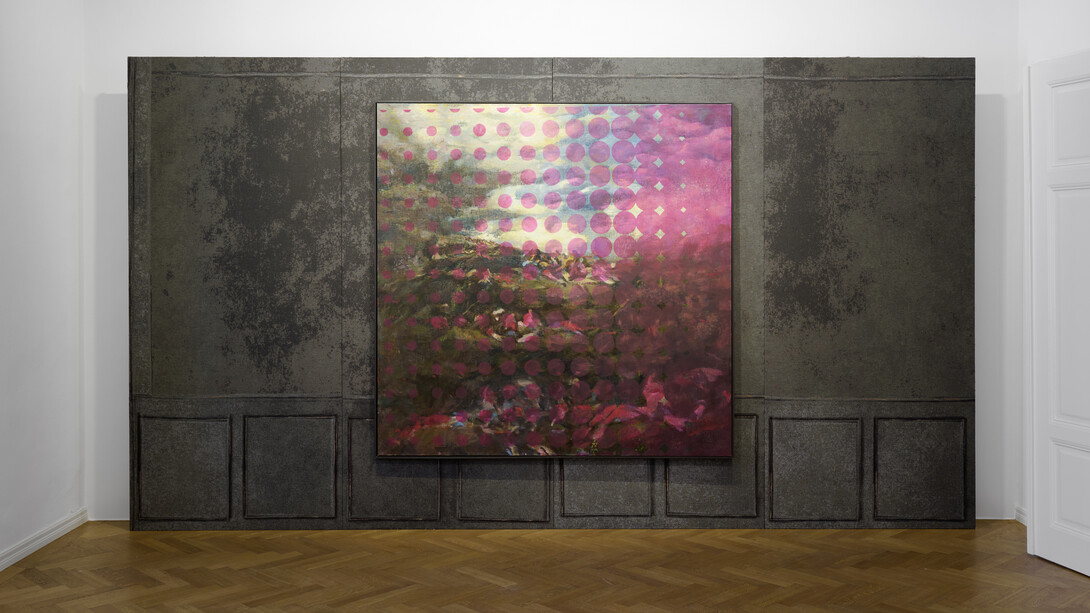

Schinwald’s most recent series of paintings, titled Extensions, is presented against the tapestried backdrop. First featured in his celebrated installation Panorama (2022), shown at the 16th edition of the Lyon Biennale, these works are distinguished by the artist’s preoccupation with the digital world. As is characteristic of his previous paintings, the restoration of historical material is an integral aspect of his artistic process. Schinwald acquires undistinguished historic paintings in antique stores or at auctions and glues or weaves them into a larger, blank canvas. Once the old image is seamlessly merged into the new base, the artist starts painting around the historic details, treating them as a mere fragment of the new composition. While the original painting determines the colour palette, brush size and impasto, Schinwald expands upon the underlying historical idea or myth, interlacing it with other narratives and contemporary aesthetics. This actively disrupts the conventional way the viewer perceives historical paintings, thereby intervening in both their constructed historical lineage and their reception. ‘I try to get as close as possible to the character of the original painting, but I use an abstract, 21st-century pictorial language,’ the artist explains.

For Untitled (Extensions) (2024), Schinwald incorporates the historical image of a sleeping woman into the lower right part of the composition, which serves as both a starting point and a marker of time. Earth tones mixed with intense dark shades seem to form a cloud over the sleeping woman, while the United Artists (UA) logo features at the centre of the work. The American film production company was founded in 1919 by Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and D. W. Griffith, aiming to give artists greater control over their work. Fusing art-historical traditions with the visual grammar of digital technologies allows Schinwald to alter the conventions of painting that ‘do not fit the climate of our time’ in such a way ‘that they can exist under contemporary conditions.’

These paintings aren’t meant to be questionnaires for history buffs or to anticipate AI prompts: rather, they are images of mourning, of contextual loss. [...] The mourning my paintings should evoke is not grieving the heroes of yesterday but the memory of the world around a work. A world that loses touch with diverse biographies and their historical context is destined for either endless consumption or utter oblivion. If we flatten everything, it all becomes uniform, and painting an image becomes a mere fetish.

(Text by Markus Schinwald)