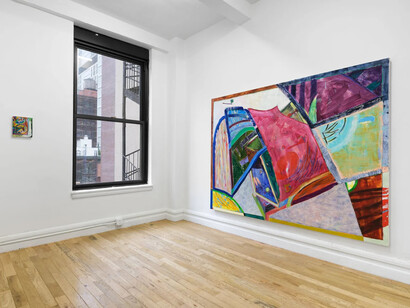

Polina Berlin Gallery is pleased to announce The lips, the teeth, the tip of the tongue, an exhibition of new paintings by Carrie Rudd, on view from October 14 through November 15, 2025.

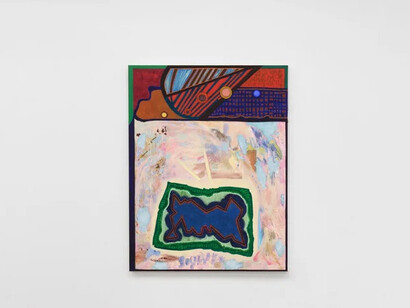

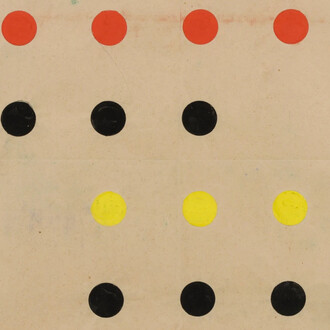

With her essayistic approach to abstract painting, Carrie Rudd dexterously edits together an idiosyncratic yet relatable collection of episodes drawn from personal experience. Although she works with the tools of a medium conventionally understood as expressive, she methodically investigates ideas grounded in language. Culling pop and personal reference into the lexicon of formalist modernism, Rudd carries forward the work of an earlier generation of artists – one thinks particularly of Rochelle Feinstein, Amy Sillman, and Charline von Heyl – who have reconsidered the possibilities for abstraction since the advent of contemporary art. Like these artists, Rudd undercuts the heroism of high-modernism by injecting her works with humor, doubt, disharmony; she sets up a number of binaries – between abstraction and representation or, in tenor, between gravity and levity – just to confuse them. Approaching each canvas as a particular problem or question to work through, the artist fluctuates between thinking and feeling, another binary made false in Rudd’s hands, as well as between predetermined compositional forms and spontaneous gestures. One suspects that Rudd’s notions may function like hypotheses, ideas tested by the process of painting. Is form like thought? Is texture like feeling? How could color factor into this equation? In part, this method draws from something like conceptual synesthesia, in which theoretical abstractions – mathematical formulas, for example, or units of time – appear visually.

At the same time, it would be incorrect to reduce these works to the realm of pure visualization. Rudd has said that her work in painting initially stemmed from her writing practice, which she maintains, furtively, as part of her studio process. The question of what painting can do, and what linguistic articulation cannot, always hovers nearby. Leaning on language while paradoxically seeking to eliminate it, her paintings ask if it’s possible to develop thoughts without words. In this conflict, there is an overarching sense of dark comedy that exceeds exact verbalization – the clash of deep, emotive hues against bright pops of color, the disruption of an AbEx field by a cartoonish blob. Yet words occasionally emerge, and might help us, as viewers, understand why we find some moments in these canvases so funny. An integral facet of the artist’s practice, titles – like Lord of the flies…with botox and Geriatric chihuahua chair challenge (after Kline) – go far in elucidating the artist’s singular comic sensibility. And as the latter title suggests, absurdist humor might catalyze this work as much as artists such as Franz Kline, explicitly namechecked here, or even Jean Fautrier, whose fromage-like textures might be lampooned by It’s still good, just cut the mold off. Looking at these works, one wonders if comedy and expressionist painting aren’t such strange bedfellows, after all. Or, to put it in other terms, maybe the stand-up comedian isn’t so different from the contemporary painter: taking material to the stage and then acting situationally, improvisationally, both expanding and transforming a longstanding tradition through their work, all while giving us something in return.

Also often like the stand-up comedian, Rudd brings a bevy of personal experience to bear on her medium – each canvas is like a dilemma or conflict grappled with in real-time, and in some way made more collectively resonant. Throughout the exhibition, the artist investigates contradictory conditions of contemporary subjectivity: the craving for authentic communication within a hyper-mediated reality; the oscillation between wily self-exposure and intellectualized concealment; the collapse of solemnity into something lighter. Her works are animated by an urgency to communicate, to work-through, and to point toward what she calls the “intermediate impossible” – spaces where seemingly incompatible forces coexist or collide. In these contact zones, where thought becomes image and gesture turns to joke, Rudd’s paintings do not seek to resolve ambiguities; but somehow in conjuring them, again and again, we begin to attain a pleasing sense of clarity. This is the artist’s impulse at work: to propose ideas with a wink, to test meaning without insisting on it, and to render visible the joys and discomforts of thinking through form.