Magenta Plains is pleased to present Joseph Nechvatal: Information noise saturation, a historical exhibition by inter-media pioneer focused on computer-robotic assisted acrylic paintings and graphite drawings on paper made from 1982–1990. This crucial period in the artists practice marks a shift in his work from an earlier, minimal aesthetic toward a complexification1 brought on by the advent of the personal computer and the internet. A concern with information noise and media overload form the backbone of Nechvatals thematic direction in these works, as he attempts to grapple with some of the defining postmodern challenges of the last forty years: nuclear proliferation, the spread of disinformation, and the rapid integration of large language models into our society.

Joseph Nechvatal arrived in New York in 1975, pursuing graduate coursework in philosophical aesthetics at Columbia University and working part-time as an archivist at the Dia Art Foundation. He quickly became embedded in the vibrant scene of the East Village, participating in the artist cooperative Colab and aiding in the founding of radical artist-cum-activist space ABC No Rio in 1980. He frequently exhibited at the Nature Morte Gallery, which was known for exhibiting deconstructionist conceptual photography, sculpture, and paintings by artists such as Gretchen Bender, Jennifer Bolande, Sherrie Levine, Ken Lum, Allan McCollum, Peter Nagy, Cady Noland, and Steven Parrino. Further exhibitions took place at Brooke Alexander Gallery, where a technician introduced Nechvatal to the computer-assisted technology he would later use to make his conceptual paintings. Throughout the decade, Nechvatals practice straddled both neo-expressionism, best represented by painters such as Julian Schnabel or David Salle, and post-modern appropriation as practiced by Cindy Sherman or Sherrie Levine, artists who enacted reproduction of imagery through a critical lens.2 However, Nechvatals consistent political praxis and commitment to using drawing and painting as tools to communicate ideas beyond an aesthetic concern sets him apart from many of his contemporaries.

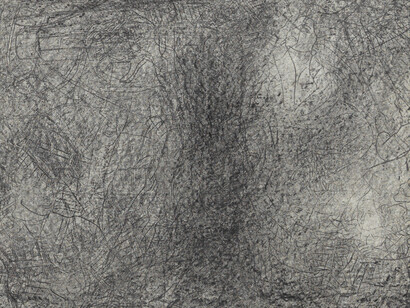

Nechvatals drawing practice from this period forms the basis for his conceptual paintings and share a common aesthetic: each work is a diptych of dense graphite edge to edge. Nechvatal created these works by laying paper on a translucent table and lighting from underneath, allowing him to achieve a layered surface of marks while working at them intensively with a graphite block until the surface of the work achieved an almost uniform smoothness. While at first glance many of these images appear to be purely abstract, imagery appears with closer inspection; in No future (1983), a police officer looks on haughtily while a civilian cowers beneath a fighter jet. The greyscale shading of these works focuses the viewers ttention on line and mark, emphasizes the immersive nature of these images, and stands in contrast to the pop color palette of many of his contemporaries.

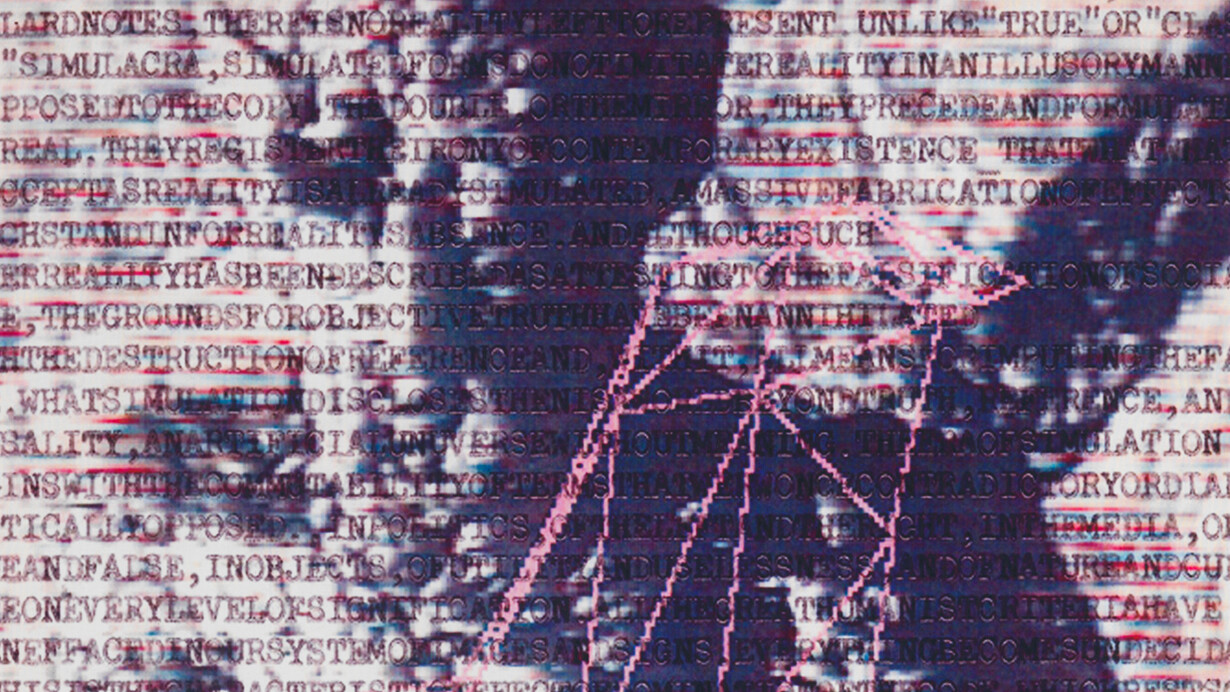

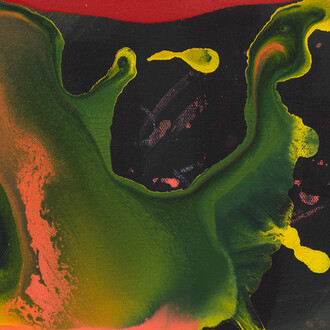

In 1986, Nechvatal began using image enlargement technology (first developed as a method for producing billboards) to digitize and magnify his drawings into acrylic paintings that are layered in a web-like, labyrinthian manner. Invented in Japan and brought to the United States by the California based company Computer Imaging Services, this process involved airbrush-painting images directly onto canvas from photochemical transparencies. This method expanded the bounds of his information-overload aesthetic, both in terms of scale and ambition. Works such as Profusely informed personage (1986) incorporate a dimensional figure wrapped entirely in xeroxes of Nechvatal’s drawings and anti-war protest posters in an immersive visualscape of chaotic marks. This mediated technology offloaded the primacy of the artists hand, foregrounding the idea and its genesis. In this sense, Nechvatal is aligned with Sol Lewitts view that a painting can be a repeatable, temporally unbound object, as opposed to a record of a creative encounter with material. In Lewitts words, the idea becomes a machine which makes the art.”

With these computer-assisted paintings and graphite drawings, Nechvatal sought to evoke the ideological manipulation at the center of mass media infotainment” during one of the most dangerous moments of the Cold War, as the Reagan administration ratcheted up nuclear tensions with the Soviet Union. Nechvatals aesthetic of subtle excess,” in his own words, functions in opposition to the pop imagery and media designed to obfuscate the bellicose rhetoric of this period. These works were borne from Nechvatals concern with nuclear apocalypse, but in today's world, they take on a new light. In our contemporary society of ideological excess and amidst an unmitigated hurtle toward artificial intelligence,” an ill-understood technology with the potential for vast economic and ecological disruption, Nechvatals work stands as a prescient warning.

Notes

1 Complexification is a process in mathematics and computing in which systems increase in complexity through spatial

differentiation and the selection of fit linkages between components, resulting in a hierarchy of nested supersystems or

metasystems. This process is driven by the need to enhance the variety of actions and to integrate these actions into

higher-order complexes to effectively respond to diverse environmental challenges.

2 Frank, Patrick. 2024. Art of the 1980s. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pgs. 7–8.