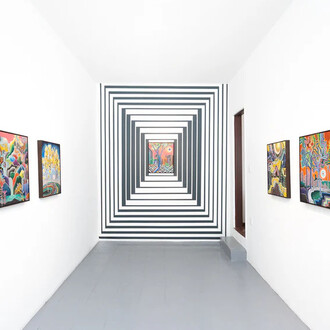

The path begins wherever a viewer first fixes their gaze. It might start in the upper righthand corner of the picture, then follow the texture of the materials, the colors, or the figures that appear in each of the works. Each piece included in the exhibition Ruido viator (Noise viator) by the Mexican-Argentine artist Ramiro Chaves presents multiple narratives that depend on how the public views them. “Viator” is a loan word from Latin, meaning wayfarer or traveler. The artist uses it to point toward people’s movement within a city, as well as to reflect on migrating, in the sense of moving both from one place to another, and from one artistic discipline to another—from photography to painting, and from the visual to the sculptural arts. He combines this with the noise and the excess of visual information that are generated in cities, and which Chaves salvages by disclosing the visual disarticulation wrought by superimposing different layers of material in each work.

In this exhibition, Ramiro Chaves presents paintings made using acrylic, clay, oil, and prints on paper, as well as found materials like cellphone screens, album covers, and bits of broken glass. Take, for example, Fogón en el puente (Hearth on the bridge), a painting in which Chaves depicts elements of nature in harmony with certain human activities, while at the same time using short brushstrokes to create layers of paint—thereby generating a uniform plasticity in the piece—and incorporating several of the materials mentioned above.

Other works on view here show the relationship between visual and written forms of language, which developed powerfully during the twentieth century as a result of technological innovations and the invention of devices that produce images and text mechanically. The piece titled Autorretrato cenizo (Ashen portrait) is an example of the artist’s interest in textual practices; in it we see a human figure made on paper with typewritten texts. The black contour defines some of the parts of that human body, like the legs, arms, and fingers so that the background of the picture could subsequently be endowed with paint. A similar exercise takes place in Sueño bajío (Lowland dream), which features typewritten words and texts while incorporating a cyanotype as the guiding line of the photographic principle. He thus uses manual techniques of visual and sculptural production such as collage, drawing in ink, and painting in acrylic, while also availing himself of techniques of mechanical (re)production like photography and printmaking on paper.

Chaves grants a central place to drawing in his work, using a marker to trace lines on paper or on photographic negatives. These forms are references to the drawing method developed by the Mexican artist Adolfo Best Maugard, whose book Método de dibujo: Tradición, resurgimiento y evolución del Arte Mexicano (1923, published in translation as A Method for Creative Design in 1949) reflects on seven motifs and signs present in the local context, the combination of which gives rise to new figures and compositions. This method was taught to students at various schools in the early twentieth century to foster their artistic capacities. The artist thus uses straight and curved lines, zigzags, circles, and spirals to represent maps, landscapes, people, and animals, as well as transitable areas in his drawings, and even in his paintings.

Chaves' work involves an ongoing dialogue with educational practice, apparent in his review of Best Maugard's method and in his study of the educator Fernand Deligny's different modes of existence. Chaves also draws on relational educational processes as a device for inquiry and artistic creation. His work as a photography teacher and studio artist has provided him with the tools necessary to operate as a creative professional. He uses photographic records, maps, drawings, texts and other archives that he has accumulated during his teaching career as a point of departure. He uses these to build an imaginary made up of objects, people, animals and elements of nature, which become visible in his painting, sculpture, drawing and photographic work.

Touring the city on foot and in vehicles forms another of the artist’s creative paths. On his travels he observes people’s movements and the presence of diverse objects in department stores, noticing the place they occupy in space. Take, for example, the sculpture Coco (2025), a piece that initially started off as a sculpture in plastic, which Chaves acquired from a place that sells second-hand items. This particular object was used as a prop for a film. The first version of this crocodile’s head was a teaching tool that Chaves used in a children’s workshop, first as an occupant of the space where he was holding his sessions, then as part of a group show organized by the members of the workshop. Eventually, Chaves ended up making a sculpture in bronze, a material he was using for the first time in his sculptural practice, creating a replica of the found object. Here we see the artist adding symbolic as well as heuristic layers to the object, causing it to take on new meaning in the educational setting, until it finally came alive as a work of art.

For other sculptures featured in Ruido viator, Chaves has used the techniques of woodcarving and modeling in clay. In these pieces we see him exploring materiality, as well as representations of animals that are still part of everyday life in certain parts of Mexico City (such as toads and ring-tailed cacomistles), together with fantastic animals he has imagined himself. As we saw the crocodile sculpture, Ramiro Chaves is creating a contemporary bestiary that invites visitors to reflect on the nature of animals.

The artist also amalgamates different disciplines from the visual and sculptural arts. We see this in his approach to the photographic principle, that is, creating images based on the effect of light on a photosensitive surface, as in the cyanotypes he includes in his collages. In addition, he regularly engages with photographic processes by integrating negatives and photographs into his paintings and drawings. This hybridization of the processes of making prints and drawing occurs in Espalda (Back), a piece that originated with a photograph of the artist’s father, seen from behind. Chaves intervened in the negative of that photograph by drawing on it with a marker and scratching it in the manner of a sgraffito. He then scanned the negative to create a layer of digital information, which led to a new work, printed in ink on paper. In this way, the piece integrates a superimposition of materials, photographic techniques, and printing processes that the artist combines in his creative practice.

Ramiro Chaves has developed a method in which the accumulation and appropriation of residual information and materials become meaningful insofar as they are displayed in parallel. His way of compressing and exploring manual and technical processes is something that definitively distinguishes Chaves’ work, as does his hybridization of craft images made by hand and technical images encoded by a device. Transgressing disciplinary boundaries, as we see in his movement between photography, drawing, painting, and sculpture, profoundly enriches the imaginary and material dimensions of Ramiro Chaves’s work.

(On Noise and Travelers by Ramiro Chaves. By Vera Castillo)