Indigenous artists and curators Heidi Brandow (Diné & Kānaka Maoli) and Shaarbek Amankul (Indigenous Kyrgyz) present a group exhibition about place, identity, memory, and creative expression within the framework of global Indigenous cultures in time for Santa Fe’s annual Indian Market.

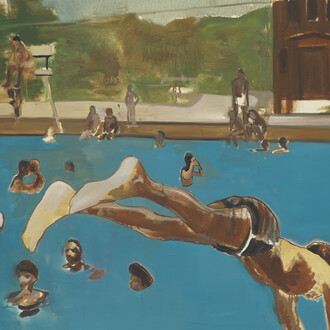

The language of place is a group exhibition featuring mixed media painting by Heidi Brandow; photography by Shaarbek Amankul; beadwork and photography by Tom Jones (Ho-Chunk); Indigenous Kyrgyzstani textiles designed by Amankul and Brandow and made by Kyrgyzstani and Uzbekistani artisans; and a pair of moccasins handmade by Clementine Bordeaux (Sičáŋǧu Lakótapi [Rosebud Sioux Tribe]). Co-curated by Amankul and Brandow, The language of place off ers a language-to-image synthesis of the grammar and syntax common to Indigenous languages in anticipation of Santa Fe Indian Market, one of the largest Indigenous art markets in the U.S. The Language of Place opens on the second fl oor of form & concept on July 25 from 5 to 7 PM.

Experience precedes language. Experience is the foundation we use to develop words and connect words to our physical reality. The inextricable link between language and environment—once apparent and logical—has grown increasingly obfuscated as the modern world evolves. Globalization and the adoption of lingua francas, such as English, means that global communication across geographically and culturally diverse regions is inherently limited by a single language’s semantic capacity. “Language shapes the way we think, and determines what we can think about,” said 20th-century American linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf. In The language of place, Amankul and Brandow ask how a return to—and propagation of—key aspects of Indigenous languages, such as connection to the land, respect and reciprocity, and Indigenous conceptions of governance and spirituality could inform or address contemporary poly-crises from climate change to polarization.

“Through diverse perspectives, The language of place examines how land, history, and cultural knowledge inform and shape the creative processes of four artists whose practices are intricately embedded in their relationships with land and environment. By blending traditional methods with contemporary approaches, the artists refl ect the dynamic interplay between heritage and modernity, highlighting the varied ways in which they engage with their cultural identities across continents,” writes Brandow.

In this exhibition, Brandow’s works recall the native and non-native fauna, such as the Saff ron Finch depicted in remembering your song, of her home, Hawaiʻi. Amankul’s works capture the fallout of social and political change in the 20th century that language fails to articulate while highlighting the resilience of Indigenous Kyrgyz culture. Jones’s photographic Krygyzstan plant studies speak to Amankul’s home and touch on Brandow’s hypothesis of cross-continental cultural understanding while highlighting the artist’s own Ho-Chunk heritage in glass beadwork. And Bordeaux’s moccasins remind us that the cultural practices we observe and perform help us traverse the constantly shifting environmental, political, and cultural landscapes that comprise our modern world.

form & concept gallery director, Carina Evangelista, cites linguist Jessie Little Doe Baird (Wôpanâak), who said, “If someone lost their land, they would say nupunuhshom (I fall down). To lose the right to one’s land is to literally fall off your feet. To have no ground under you. My land is not separate from my body.”