The Usumacinta River, stretching from the highlands of Guatemala to the Gulf of Mexico, is known as Mexico’s “last living river” because of its uninterrupted flow and the extraordinary diversity of plants and animals it still sustains. Its modern name bears the imprint of overlapping colonial encounters: in the 16th century, Spanish chroniclers recorded the Náhuatl name “Usumacinta”, which they translated as “the river of the sacred monkey.”

Traces of the Usumacinta’s pre-Columbian past can be found at numerous sites across its basin, where the ancient Maya built cities and carved elaborate stone monuments. These carvings—known as stelae—have long inspired wonder and scholarly study, even as they have been removed or damaged by various kinds of extractivism.

In ancient times, Maya stelae served as chronological records, but unlike the statues of Western traditions that commemorate political actors and their feats, they were considered the living embodiments of rulers, preserving their presence and power beyond their earthly lives. So intimate was the bond between stelae and their settings that these monuments were identified with both a stone glyph and an accompanying plant or tree glyph—suggesting that, like the forest itself, stelae sprouted from the jungle floor.

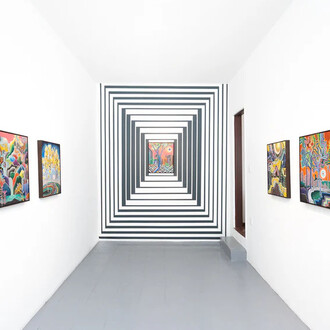

In this exhibition, we play on the dual meaning of the word “stela.” On one hand, the carved stone monuments; on the other, the foamy wakes that linger on the river’s surface long after a boat has passed. Though fleeting, these ripples shape the river’s course. Both kinds of stelae—stone and foam—are traces, turbulences that make the absent present.

Today, the Usumacinta basin bears the scars of a long history of plunder. For over a century, its forests were cleared for tropical timbers and chicle; its stones were sawed away and shipped to museums and private collections around the world. In recent decades, cattle ranching, monocrop plantations, and the relentless drive of tourism and scientific inquiry have further ravaged its lands and imperil its future.

Through video, photography, sculpture, archival materials, and obejcts from the Museum’s pre-Columbian collections, this exhibition invites you to consider: how might the river be reconciled with all that has been taken from it?