It is a crystal clear fact that the term posthumanism covers quite numerous fields, from gender studies to laws and ethics. No matter how intriguing the topics in those fields are, this article will not go through a detailed treatment of posthumanism. Various definitions for posthumanism pursuant to the science fiction genre will be supplied by making etymological references to the literature in order to provide a basis for the article. The article will also attempt to define posthumanism in comparison to humanism. Moreover, transhumanist theory will be introduced, and the breakup point between transhumanism and posthumanism will be pointed out.

Before defining "posthuman," I believe it is important to know what is defined as "human" to have a better understanding of what is considered to be "posthuman," as it is a deconstruction of the idea of humanism. The term “human” comes from the Latin word “humanus/a/um,” meaning “civilized” to Ancient Romans. Meanwhile, for Ancient Greeks, this civilized Anthropos, who is a political man, doesn’t include women, slaves, or barbarians who cannot speak their language; therefore, they were not considered human, as Greeks defined man as an animal with speech1.

Since history is mostly written by white European male historians, humans are portrayed essentially as male, white, and presumably heterosexual. However, post-human includes socially oppressed groups (women, LGBTI+, etc.) as well as nonhuman subjects such as animals, aliens, and plants. Unlike humanism, posthumanism doesn’t place humans at the center of the focus to understand the world, but rather it includes animals, plants, and their relation to their environment. Posthumanism, being an umbrella term, addresses different aspects of the theory.

Therefore, Posthumanism can be approached from different angles. Even though there are many more approaches to defining “post-humanism” in the literature, this article will focus primarily on Critical, Cultural, and Philosophical Posthumanism(s) 2, which are by nature related, as well as Sherryl Vint’s classification of posthumanism. The initial two concepts introduced by Francesca and Braidotti—Critical Posthumanism and Cultural Posthumanism—are closely interconnected, both interrogating the notion of the "human" subject through the lenses of gender and cultural studies.

In contrast, the latter concept shifts focus by decentering the human in relation to the "nonhuman." Sherryl Vint, in her Posthumanism and Speculative Fiction, categorizes posthumanism into three groups. The first group is made of what she calls an uber-human, that is a human being with superior power, strength, intelligence, or some sort of evolutionary or technological mutation. 3 The second refers to the new humans who are subordinated such as women, the poor, the colonized, the proletariat, or LGBTI+.4 In this regard, the second classification is more related to the critical and cultural posthumanism of Francesca and Braidotti. It questions how the definition of human has evolved within the borders of the laws of society. The last group covers nonhuman beings: animals, robots, AIs, plants, aliens, and such5 which questions the essence of being a human compared to what is considered to be nonhuman, asking the question of what a human is made of.

As can be seen from the above examples, it is possible to approach from different directions to define what is posthuman as it has many relations to various fields. As I thought using AI to define something closely related to its existence would be interesting, I asked ChatGPT, an AI that is developed to facilitate human life, what posthumanism is. According to a ChatGPT post, posthumanism is “a notion that questions what it means to be a human, a theory that looks at life, identity, and existence outside of the conventional definition.”

With the help of AI, we have already stepped into the posthuman era. In the future, the possibility of ChatGPT having its own idea rather than being a big pool of information is thrilling, as it could be seen as another branch in the evolutionary tree. However, achieving true autonomy requires more innovations in the field as well as some answers to the ethical and philosophical challenges. Theoreticians like Francesca Ferrando in her way question some of these philosophical challenges. She treats posthumanism as a philosophical and theoretical idea that reacts to anthropocentrism in the 21st century.6

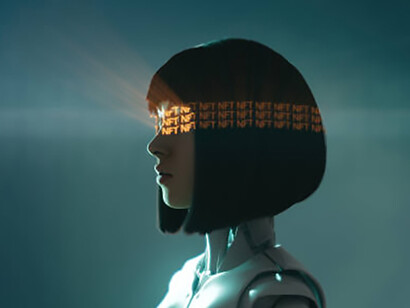

In other words, anthropocentrism, as the name suggests, centers the human as the most important entity in the universe, while posthumanism rewires the traditional binaries such as human/nonhuman. The nonhuman, quite simply, is what we are used to seeing in (mostly cyberpunk) science fiction movies as androids, robots, a symbiosis of a human and nonhuman. In this regard, the correlation between posthumanism and cyberpunk science fiction iconography is substantial to tackle. The elements that create the iconography, such as the use of AI, futuristic technology, alien life forms, and androids, tend to be considered as posthuman or transhuman because of the way of the representation of the integration of technology into society.

Posthuman, in this sense, is a state of being able to coexist with other life forms (animals, plants, aliens), pushing the limits of the flesh with the aid of technology. At this point, the fine line between posthumanism and transhumanism becomes very blurry.

Before delving into the meaning of Transhumanism, it is important to assert that the two notions, posthumanism and transhumanism, cannot be seen as totally separate concepts. Posthumanism and transhumanism emerged at the same time during the 1990s7. Although posthumanism comprises transhumanism to a certain extent, their roots and standpoints differ. To begin with the etymological roots for transhumanism, the first use of the term belongs to Dante Alighieri in La Divina Commedia, with the verb “trasumanar” meaning going beyond the human, although the term is coined by Julian Huxley in an anthropocentric way.

Although both transhumanism and posthumanism challenge the essence of the human, the roots of transhumanism trace back to the Enlightenment in Europe during the 18th century, referring to human enhancement, while the roots of posthumanism lie in humanism (which can be traced back to the Renaissance). This historical divergence between transhumanism and posthumanism sets the stage for a broader debate about the current state of humanity, specifically the ongoing question of whether we have already transitioned into a posthuman era.

Another conflict underlies the question of whether we are posthuman yet. For Transhumanists, we are not but some of us who are already merged with technology more and more can be defined as transhuman with a hybrid co-existence with science and technology. For example, can a war veteran with a bionic limb be seen as a cyborg? Then, how should we define transhumanism? Transhumanism suggests an enhancement of human beings with the help of nanotechnologies such as gene repair, eugenics, and cloning to become posthuman. This enhancement should serve the benefit of humankind; it should make humans more intelligent, healthy, and happy and make life easier for humans by forcing and taking control of the limits of our nature.8

Although they are interrelated, briefly, transhumanism aims to improve the human condition for better performance and a better future with the help of technology. Technology must serve as a tool to help humanity to facilitate their lives. Even though they share overlapping concerns regarding human nature, posthumanism doesn’t have specifically this kind of aim. Posthumanism is more critical of the use of technology, besides offering a broader ethical critique in various fields.

Just like posthumanism, transhumanism has different schools of thought. It can be studied under four typical movements: Libertarian, Democratic, Extropianism, and singularitarianism. Libertarian transhumanism supports a free market for human enhancement, while democratic transhumanism claims equal access to technological enhancements in order not to create an imbalanced power distribution between sociopolitical classes. While these two transhumanisms deal mainly with social, political, and economic aspects, Extropianism relies more on the individual and self-transformation, and Singularitarianism covers future conjectures regarding human enhancement in an irreversible way.9

The traces of Posthumanism and Transhumanism mostly are questioned in Cyberpunk Science Fiction genres. Perhaps the genre’s iconography is more suitable to host such an experience. In audiovisual mediums such as films and graphic novels, it is possible to witness repetitive thematic elements that are associated with the genre. Cyberpunk, as a genre, provides a space for exploring complex thematic elements such as the tension between humanity and technology, the erosion of individuality, and the rise of artificial intelligence. Central figures in these narratives include robots, cyborgs, androids, and AIs, each representing different aspects of posthuman existence.

These themes are often set against a backdrop of a postindustrial, consumer- driven society, where dystopian visions of the future emphasize social decay and technological domination. Visually, cyberpunk is characterized by a distinctive aesthetic: a depressive, overwhelming skyline filled with towering skyscrapers, neon lights, and holograms. The often grey, polluted atmosphere is punctuated by the contrast of artificial brightness, creating a sense of alienation and technological excess. For example, should the portrayal of robots and androids be considered in the cyberpunk science fiction genre, they are generally metallic, lack emotion, and operate on logic, although androids have a sense of humor compared to robots.

However, cyborgs are a mixture of a human and machine; they look like humans, and sometimes it is hard to distinguish them from “real” humans, which makes them the feared unknown. The costumes are designed to be futuristic and sometimes surreal, since the actors are characterized as the contemporaries of a dystopian cybernetic future, their acting is rather similar to robots, stripped of intense emotion. In time, these elements evolved and created a solid iconography for its audiences to identify cyberpunk better.

It is deemed worthy to refer to the significance of understanding cyberpunk culture when relating it to post-humanism and transhumanism. Cyberpunk as a subgenre of science fiction rose in the mid-1980s, describing a dystopian life that is a combination of high technology and low life (where people live a disenfranchised, poor-quality life), having characters who live on the fringes of society.

One of the reasons why Cyberpunk emerged in that era is that it was a response to the representation of the cultural environment of the time. The 80s America was turbulent as the center-left government of Democratic President Jimmy Carter was displaced by Ronald Reagan, and this led to decadence in the society. By the 80s people had lost their faith in the government and politicians. Since the 70s the society has faced accelerating inflation, slow economic growth, and rising rates of crime, divorce, and drug abuse.10

Cyberpunk reflected on this with a portrayal of street-level anarchy in a dystopian world. If examined with a philological approach, the term “cyber” is derived from the Greek word “kubernetes,” meaning “pilot” or “steersman”. This implies the underlying aim of cyberpunk, which is to use technology that is designed to control people to fight against technology. Punk, on the other hand, means “rotten” or “junk.” A “Punk” is a rebel, anarchist, or troublemaker who is usually imagined to wear a leather jacket.

In cyberpunk science fiction, this punk usually refers to an anarchist and anti-authoritarian rebellion. In light of its etymological analysis, the rise of cyberpunk in American society in the mid-1980s is not shocking, as American society was more concerned with the advance of technology: computers started to get so much prominence that even Times magazine entitled a personal computer to the “Man of the Year” award. This acceleration in computers receiving human attributions caused Americans to ponder about the transcendence of machines, forms of coexisting with the latest technology, or the risks that it might bring, such as the increase in unemployment or violation of the privacy of personal life.

The response came from different aspects, including literature (Neuromancer by William Gibson), film (Blade Runner, The Matrix, Ghost in the Shell), fashion (a blend of retro and futuristic style with dystopian grunge, dark leather, neon colors, and a synthesis of several cultural components), and tech business (Silicon Valley, Google, Amazon, Apple, and Facebook) in a socio-political critique. By treating themes of virtual realities, hacking, freedom, and identity, cyberpunk criticizes contemporary issues such as socioeconomic inequality resulting from power imbalance in the corporate world and tech ethics.

In addition to common motifs that the genre features, such as moral decadence and the contrast between high technology and low life, the landscape and the characters of the genre are quite idiosyncratic. The landscape of the cyberpunk science fiction genre, having similarities with noir films, almost mirrors this decadence, where the sky is stilted as it is occupied with ads of high-tech products, giving a sense of entrapment and symbolizing the consumerism and control of mega-corporations. For example, movies such as Blade Runner (1982), Akira (1988), and Ghost in the Shell (1995) describe futuristic depictions of Tokyo-like cities, towering skyscrapers, and neon-lit crowded streets.

While the rich live in the high skyscrapers, the poor try to navigate in the shady, decaying streets. The constant rain and dusky and polluted weather have been allegorized with the corruption of society. In Ghost in the Shell, the scene where Major Kusanagi jumps from a skyscraper and becomes invisible against the landscape can be seen as a metaphor for how the city swallows the sense of identity among the crumbling and decaying urban environment, dilapidated buildings, and rainy streets, which give the noir aesthetic to the cyberpunk genre. In Akira, the streets of Neo-Tokyo become the stage for rebellion and protest against government oppression. Buzzing with biker gangs, violence, and chaos, the streets encapsulate the cyberpunk spirit.

Contrasting the crowded streets of cyberpunk, the characters are usually portrayed to be alienated and lonely, but just like the city, the protagonists are morally ambiguous, anti-heroic figures living on the edge of society. Even the aesthetic style of the cityscape shows a resemblance with characters wearing grungy trench coats or leather, having cybernetic body parts, or having neon-lit accessories. In almost all cyberpunk narratives, the protagonists are rebels against oppressive entities (such as corrupt governments or big corporations).

In the pursuit of individual autonomy, they use their skills to explore the blurred line between humans and machines. For example, Deckard in Blade Runner, being a lone detective who eliminates bioengineered beings, questions his own morals and understanding of humanity after he confronts Rachel and Roy. Deckard is not the only protagonist who has an existential and identity crisis; Major Kusanagi also contemplates what it means to have a “ghost (a soul or consciousness),” and Neo in The Matrix seeks to find out what it is to be “real” or “programmed.”

These bring up the question of why posthumanism and transhumanism are important to understanding cyberpunk culture. Cyberpunk provides a medium to explore the boundaries of human nature as well as question the human essence. The Cyborg itself is a hybrid of a human and a machine that does not have the physical limitations of a human, is not bothered by the fluctuations of emotions caused by chemicals, and is flawlessly efficient.

Despite the practicality and modernity of the cyborg, according to Despina Kakoudaki, the metal exterior represents a type of otherness or abjection in the position of blackness for Western “modernity” by embodying African slaves. “Distinction between human and nonhuman, depicting dangerous or deadly competitions between people and robots that reference racial and political registers of difference and are aggravated by Cold War paranoias”.

Cyberpunk culture, while nurturing transhumanist and posthumanist theories, can also criticize and represent history. In the Hatzfeld Tetralogy, the reflection of the trauma of the collective memory of the post-Cold War period, with an emphasis on the Balkan crisis during the 20th century and the breakup of Yugoslavia, is presented by using posthuman and transhuman elements with political allegories through Enki Bilal’s eyes.

By taking into consideration its point of origin, cyberpunk as a genre is the most post-humanist of all because of its portrayal of moral and cultural decadence in a futuristic dystopian world caused by technocracy and its exploration of the definition of the human through science and technology.

In conclusion, posthumanism can be defined under the subcategories of cultural, critical, and philosophical posthumanism, yet posthumanism is a vast concept sharing some common ground with transhumanism, although they have different roots. Just like Posthumanism, Transhumanism can be studied in different aspects, such as Libertarian, Democratic, Extropianism, and Singularitarianism. Nurturing reciprocally with Posthuman and Transhuman theories, the world of the Cyberpunk setting is also shaped by neoliberal economics in a dystopian capitalist tech noir aesthetic. As it is exemplified before, historical milestones can trigger the progress of portraying dystopian cyberpunk landscapes; thus, synchronously, the posthuman and transhuman can be shaped according to these formations.

References

1 Ferrando, Francesca, and Rosi Braidotti. “Chapter 17: Where Does the Word ‘Human’ Come From?” Philosophical Posthumanism, Bloomsbury Academic, London, 2021, pp. 89.

2 Ferrando, Francesca. “Chapter 10: Philosophical Posthumanism.” Philosophical Posthumanism, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019, pp. 54–62.

3 Vint, Sherryl. “Posthumanism and Speculative Fiction.” Palgrave Handbook of Critical Posthumanism, 2022, pp. 1–22.

4 Vint, Sherryl, pp. 1–22.

5 Vint, Sherryl, pp. 1–22.

6 Ferrando, Francesca. Posthumanism, Transhumanism, Antihumanism, Metahumanism, and New Materialisms: Differences and Relations.

7 Ferrando, Francesca, and Rosi Braidotti. “Chapter 3: Posthumanism and Its Others.” Philosophical Posthumanism, Bloomsbury Academic, London, 2021, pp. 27.

8 Sampanikou, Evi D., and Trisje Franssen. “Chapter 2: Prometheus Redivivus: The Mythological Roots of Transhumanism.” Audiovisual Posthumanism, Cambridge Scholars Publishers, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2017, pp. 27.

9 Ferrando and Braidotti, pp. 31-32.

10 YU, Zemei. “What put ‘punk’ into the Cyber World?—the punk flavor in the Cyberpunk Science Fiction.” Comparative Literature: East & West, vol. 17, no. 1, Oct. 2012, pp. 88–102.