Fragment mapping of our living spaces

« I show what is »(Max Charvolen)

The first impressions made by Max Charvolen’s works are often the same: the viewer is confronted with an enigmatic object that feels familiar in some vague way. This gives rise to the formulation of all sorts of hypotheses.

Having long observed the reactions of the public during presentations of Max’s work, as well as read the texts written about him, I was first struck by the diversity of approaches. And then by the recurring impression shared by many: something in these pieces evokes images of transfer, movement, and travel.

I will return later to the diversity of approaches. For now, I prefer to start by addressing what induces the impression of movement. In fact, I came to find it almost self-evident, as movement is a central issue in Charvolen's approach and processes. I will present this briefly, while remaining as close as possible to his work.

Since the late 1960s, Max Charvolen has been exploring the relationship between the artwork—let's say the « plastic » or « symbolic space »—and the location in which it is created and/or exhibited—let’s call it the « physical, » « living, » « working, » or « viewing space. » At that time, he transformed the canvas by cutting it, either respecting or breaking the initial rectangle, fragmenting it, shifting the fragments, and exploring the different ways in which the completed piece could be viewed as well as the effects induced by the position of the viewer.

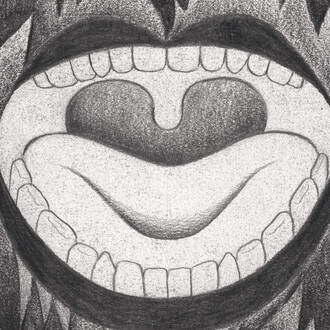

By the late 1970s, his approach became more radical: the artist no longer installed an artwork in a random space once finished. Instead, it was a work he conceived and created to fit a specific physical space. After cutting his fabric into fragments of a size that could easily be grasped, held, and manipulated with two hands, he would then glue these fragments onto the spaces (or objects) he wanted to « reveal. » The shape of the completed canvas thus depended on the space in which it was created, which became, literally, a model. Its format was born from the artist's physical relationship to the space: more or less active, moving more or less to « take measure. » The coloring of the fragments serves several functions. For example, the diversity of colors allows the differentiation of various elements or planes of the model.

Once the collage overlay was completed, the artwork was left in place while it dried, a phase the artist could prolong for varying lengths of time, sometimes even for years. During this drying period, the canvas continued to transform due to the use of the space on which it was created : traces of movement, dust, debris, etc.

At the end of the drying period, the canvas is torn from its mold - one can imagine the physical effort required for this operation, thus retaining the memory of the volume on which it was formed, and sometimes elements of the architecture. What results from this process is : a skin, a shedding, a carcass that Charvolen later wants to present as flat as possible. As anyone who has experimented with a cube’s volume can attest, the flattening process implies cutting some of the cube's edges. Thus happens the classic passage from the three dimensions of physical space to the two dimensions of plastic space. When the completed canvas is ready to be exhibited, the questions of display arise, often in very unusual ways, due to the works’ unusual dimensions and unexpected formats.

This is where Charvolen’s approach and processes can induce the idea of movement. Movements of the viewer to look at the object, movements of the artist to create it, movements of the fragments, movements of these « space skins », from the habitat on which they were molded to the space in which they are shown. One more detail on the topic : Charvolen does not create his works in a permanent studio. He is a nomadic artist and every space he occupies becomes his studio.

Why, then, does one feel that these strange shapes somehow relate to spaces we have known, inhabited, and crossed ? The artist’s choice is key here. He selects nodal places, places of passage, stairs, doors, windows : « what is », where we stand and where we pass.

Charvolen’s unique approach explores the issues raised by the analytical and critical approaches from the 1960s to address questions that run through the entire history of art : what should we represent about the world in which we live, about our spaces and objects ? How should we represent them ? In which places and contexts ? How do we transition from the three dimensions of physical space to the two dimensions of plastic space ? How do we explain the formats we use and the shapes we give them ? How do we account for the world through painting ? How do we think about it ? How do we give meaning and reason to our sensitive approach to the world ? Can we reignite, give meaning back to the symbol by reconstructing/reconstituting it from what it first symbolized : the physical space in which we evolve ?

I mentioned the diversity of approaches and hypotheses regarding Charvolen’s work. It seems useful to clarify one of the reasons for this. Charvolen's work has intrigued experts from a variety of disciplines. Alongside art historians, there are mathematicians, historians of science, poets, novelists, prehistorians, philosophers, semioticians… The diversity of approaches is thus at least partially explained by the variety of disciplines involved. Jean Arrouye also attributes this diversity to the personality of the viewer. He notes that : « If Max Charvolen’s works always make such a strong impression, perhaps it is because they stir undefined areas of deep emotionality. This is not necessarily the case for every viewer, but the images created (in both the archaeological sense of uncovering what was waiting to be discovered, and the inventive sense of creating something new) by Max Charvolen always invite imaginative drifts. »

It is hard to resist the temptation to add a few quotes picked up here and there to make an arrangement.

I say « arrangement »... it is interesting to see how flower metaphors settle in seemingly unrelated reflections.

When analyzing the transfer of information between the spatial model and the finished piece, Mathematician René Lozi writes : « When I tried to understand what has, for forty years, unified Max Charvolen’s work in a continuity, beyond the obvious operational procedure (…), a metaphor patiently settled in my mind : the reproduction of the marsh iris (...) with seeds that can float on water for a year while retaining germinative power, and rhizomes working underground before resurfacing. We are drawn to the flower, we look at it, sometimes we admire it, we may try to describe it, decompose it, dry it in a herbarium; but the underground rhizomes escape us and they bring other flowers to the surface. »

This is echoed by a text written by Michel Butor with an unusual beginning : « When a powerful Egyptian man of the Old Kingdom wanted to bring with him all his familiar companions across death, he had them depicted in bas-relief or painting on the walls of his tomb, striving to make them as present as possible, thus as identifiable in their posture and profession. »

Then, after considering : « he folds, (which are) closer to those found in cutouts for children and adults, which must be detached and folded, sometimes glued to create fragile miniature models that can be manipulated for display », Butor introduces an image whose apparent triviality and, ultimately, effectiveness, is for everyone to appreciate, before drifting towards blossoming : « One must then consider all the faces to be separated from each other, like a butler disarticulating the limbs of a pheasant. But all the joints that can unfold on a plane are kept in such a way as to make the future object stronger. The resulting shape constitutes an often-unexpected development of the familiar instrument or piece of furniture. Surely, we can recognize each face when we abstract it from the others, but it is the whole that produces a sort of blossoming, of which the common object was only the seed. »

The « blossoming » is not the only image our expert friends use to fuel their reflection. The image of the skin naturally emerges in the writings of semiotician Nicole Biagioli, who writes : « Charvolen's skin-prints connect the space-time of their creation to that of their successive exhibitions, which requires integrating the display into the very definition of the work. Thus, the work is renewed each time it moves to a new place. »

In fact, the title of her text, « Mu(es)tations on the Work of Max Charvolen », already gives a clue. Further pushing the idea of skin, and almost confirming these "space-time" movements, historian Renato Barilli presents an unexpected picture : « Charvolen behaves like a hunter who, after bringing down a majestic prey, a pachyderm, kneels around its carcass to extract very thick chunks of skin deeply incorporated into the animal's flesh and bones. [...] The terrible fatigue of the artist-hunter, entirely absorbed in retrieving « his » skin, armed with a knife with which he must cut through the fabric, make an opening, and then widen it with the strength of his wrist to painfully tear it apart.

This naturally brings to mind the title of a text by François Jeune, which beautifully echoes the scene described by Barilli : Max Charvolen, A Contemporary Parietal Art. How could one be surprised that, at the Lascaux 4 site, Jean-Paul Jouary included Max Charvolen among the contemporary artists engaging in dialogue with prehistoric art ?

At this point, it is time to end the text and the arrangement, to leave many other approaches in silence. I regret this... However, one more angle, still important to me, needs to be explored.

I first borrowed it from a text by Claude Fournet, a museum curator and poet : « Whether it's a walk, a window, or a door, what is imprinted, distorted, or imitated constitutes the painting (...) Something coincides and does not coincide, is and is not the painter, expresses too much and falls silent. The place of dwelling is also the place of mystery and poetry. »

The word is out: poetry. Let us then finish this arrangement as we began, by reading Jean Arrouye : « The perception of the topography of the original place is lost in this operation (of transferring the canvas, RM notes): it is as if, as poet Jean Todrani says in « Matériaux de la solitude », « objects free themselves from their form and the prisons of their use. ».

In doing so, the work acquires a poetic dimension, since, as Marc Chardourne reminds us, « poetry begins where reality loses its rights. ». And Michel Butor titles the text he dedicated to Charvolen I referenced at the beginning of this arrangement : « The House of Our Dreams. »

(Text by Raphaël Monticelli)