Mindy Solomon is pleased to present Venezuelan born; Antwerp based artist Ricardo Alcaide in his first solo exhibition in the gallery.

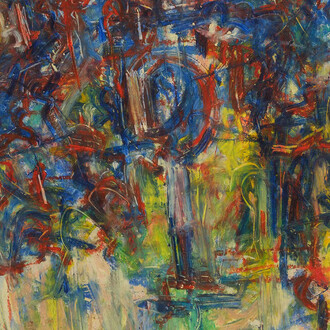

There is a quiet tension in Ricardo Alcaide’s work—an insistence that what we often overlook has weight, memory, and meaning. In Brightest light, he presents a new body of work that distills years of lived experience into a material language that is both ordered and unruly.

Alcaide’s compositions begin with the logic of construction: bars of aluminum or MDF, aligned with near-clinical precision, marked by repetition and control. But he never lets them settle. Paint spills beyond the lines, edges are scuffed or left raw, and bricks are inserted where they can’t perform their function. In works such as Silence and Visible, the works appear sharp and clean from the front, even minimalist. But take a step to the side, and their skin peels back. Imperfection reveals itself as a method. Mess becomes the message.

For the first time, Alcaide turns to aluminum—a reflective, industrial material he had long resisted. In these new wall-mounted reliefs, the aluminum’s smoothness contrasts sharply with the rawness of embedded bricks and the rough brushwork along the edges. These aren’t just aesthetic choices but acts of resistance: against polish, against pretense. If the surface remains smooth, it does so, bearing inner scars.

In one of his recent works, Alcaide found himself unexpectedly echoing Venezuelan modernist Alejandro Otero. Like Otero’s Colorhythm series, his vertical compositions pulse with rhythm and modularity. But what Otero sought in purity and optical harmony, Alcaide interrupts with bricks and intentional sloppiness. His is not a celebration of order but a slow unraveling of it. What stays is tactile and restless, a structure marked by the evidence of its own making.

The brick, recurring throughout the exhibition, first entered Alcaide’s vocabulary while living in São Paulo. There, he encountered bricks everywhere throughout his walks in the mega-metropolis—stacked on sidewalks, tucked into windows, and left abandoned on street corners. To him, they became a symbol of the city’s informal architecture, its unfinished edges, and its capacity to hold weight without fanfare. Alongside MDF—a material he came to know intimately while working as a handyman in London—the brick embodies Alcaide’s ongoing commitment to what is often dismissed or covered up. Both are materials that usually live behind the wall. Here, he gives them visibility—foregrounding their presence rather than concealing it. In this, Alcaide’s impulse recalls Hélio Oiticica’s embrace of the marginal as a social position and a creative force. The use of brick, MDF, and other industrial materials is not simply to represent the everyday but to create from it.1

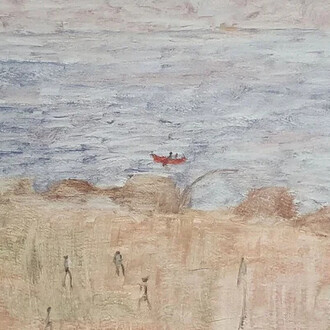

Despite the material heft of aluminum and brick, lightness permeates the exhibition—conceptually and chromatically. The show’s title and orientation take inspiration from the sun, light, and Alcaide’s emotional response to Miami’s brightness. A sequence Alcaide calls his “rainbow of chaos” derived from a graffiti he once saw in downtown Miami that read, “We live in the rainbow of chaos.” These personalized rainbows evoke joy and spiritual charge layered over the grid’s rigidity. At once intuitive and formal, this palette reflects Alcaide’s desire to channel sensation through geometry—translating emotional landscapes into structural terms.

Taken together, the works in Brightest Light offer a sensorially rich meditation on what lies beneath appearances. If modernism once promised clarity through order, Alcaide answers with aesthetic friction—embracing the residue, the error, the humble. His practice evokes what curator Mari Carmen Ramírez called the ‘fractured utopias’ of Latin American modernity, where formal purity often collided with the social realities it sought to transcend.2 Yet Alcaide’s work is not a didactic language—but one of intuition, memory, and personal reinvention. Having lived between Venezuela, Brazil, the UK, and now Belgium, his work remains rooted in displacement, reassembled through a careful choreography of material, memory, and mark-making. In Miami, it comes full circle—an encounter with light again.

(Text written by Jennifer Inacio)

1 Hélio Oiticica, “Appearance of the Super-Sensorial,” in Hélio Oiticica, ed. Guy Brett (London: Tate Publishing, 2007), pp. 114–118.

2 Mari Carmen Ramírez, “Blueprint Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America,” in Global conceptualism: points of origin, 1950s–1980s, ed. Luis Camnitzer, Jane Farver, and Rachel Weiss (Queens Museum of Art, 1999), pp. 54–61.