When one is discussing the future of work and AI, everyone believes that artificial intelligence will not displace artists. Actors, painters, and writers are generally said to impart something uniquely human—feelings, intuition, fantasy—and therefore will be safe from the job-hunting predator that is AI. But despite being as human as any medical man or engineer, artists are often treated as if they are stardust—blessed with some kind of magical awareness that renders them invulnerable to technology and keeps them creative and unsullied from the supposedly filthy virtual world.

This idealized image supposes creativity to belong exclusively to human beings and, still more exclusively, to people having brushes, pens, or cameras at hand. But history—and nowadays—imply a finer picture.

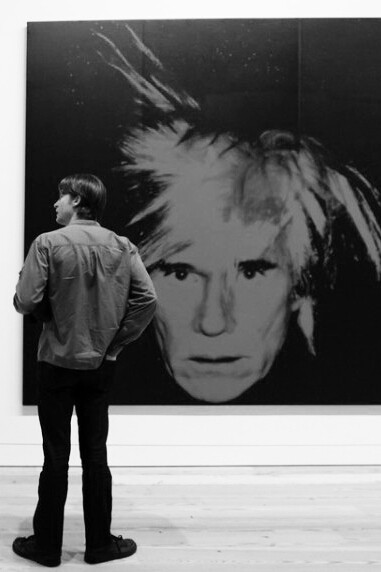

Van Gogh, Picasso, Monet, and Leonardo da Vinci are but some of the iconic painters renowned for their genius and revolutionizing brushstrokes—works of art that, until now, belonged entirely to man. Their works have been fashioning art majesty throughout the annals of history and geography. But we also forget that innovation is not just for the past or even traditional media. Creators like Andy Warhol, for instance, not only predicted the era of "15 minutes of fame"—something now reduced to daily occurrence on the likes of Instagram and TikTok, where one has their platform but did not exist with such extensive reach before—but also consumed new technologies hungrily.

The reason I'm painting this way is that I want to be a machine.

(Andy Warhol)

Warhol would have been most likely to have welcomed AI as a creative partner. In fact, in a Netflix biopic documentary on his life and work, AI is used to mimic his voice—overcoming the line between man and machine, art and reproduction. Warhol went so far as to experiment with robotics, even attempting to duplicate himself as a model robot—a move that, today, looks almost prophetic.

Warhol was not the first to push the limits of art and technology. Half a millennium earlier, Leonardo da Vinci was playing with the art of seeing and is thus an obvious historical candidate for an artist who would have inevitably been fascinated by AI as a means of discovery and creation. While the Mona Lisa remains his most iconic hand-painted work, da Vinci also laid some of the conceptual groundwork for photography—centuries before it became a reality. The first actual photograph wouldn’t be taken until 1826 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, but da Vinci’s deep fascination with optics, light, and the anatomy of the human eye anticipated the visual principles that would later shape both photography and cinema.

He was particularly intrigued by how light enters the eye, the nature of shadow, and how depth and perspective could be transferred onto a two-dimensional plane. These experiments—seen and driven by limitless curiosity—not only rendered his art aesthetically phenomenal but also scientifically revolutionary.

Being as it is, it's still not particularly probable that AI would, independently, produce a painting like the Mona Lisa—a work of art that, over the course of centuries, has absorbed layers of myth, interpretation, and mystery. From mathematical proportions to anatomical allusion and tacit symbolism, this kind of depth is something software lacking lived experience and emotional awareness cannot easily provide. The machine can reliably replicate aesthetic style, but can it possibly give a canvas significance transcendent of time?

But the question remains: Is creativity still something specifically human? Or are we witnessing the birth of a new form of artist—one who is born not of emotion and memory, but of data and code?

Along comes Refik Anadol, a Turkish-American new media artist, director, and futurist when it comes to AI-generated art. A master at breaking data down into interactive spaces, Anadol gives us a glimpse of what the future might hold, where humans and machines are in creative partnership.

He even coined the phrase "data painting" to describe a new visual lexicon—one in which data is color and algorithms are the brush. In his art, he attempts to discover the unseen for human eyes: patterns buried deep within large sets of data, machines' subconscious, or the city's collective memory. He realizes these things we don't usually see—such as brain activity, ocean currents, or satellite imagery—converting raw data into whirling, surreal digital designs through large-scale installations.

Although Anadol was never able to draw or paint traditionally, he redefined what it means to be an artist in the digital age. In a 2023 interview with Louisiana Channel, he described, "AI is an extension of my mind." For him, art remains a human endeavor, but AI is a powerful assistant—an instrument that expands what one can do.

Anadol is not afraid to get to the ethical and philosophical issues of AI. He sees the dangers—from bias in training data to deepfakes and job displacement—but believes that, like any tool, its impact depends on how we choose to use it. "We should not be afraid of the machine," he says, "but learn to speak with it—to educate it in empathy, beauty, and poetry."

This evolving relationship of human and machine is not the demise of art, but its transformation. It beckons new forms of expression, new publics, and new questions. What does authorship look like if art is written by a machine? Can a machine perceive nostalgia? Can it dream?

These are not merely technological questions—they are essentially human ones.

Standing on the doorstep of a new age of technology, we must steer clear of polar extremes: the zealous rejection of technology and uncritical embracing. AI will not steal our stardust from the creatives—but is forcing us to redefine what art is, who can make it, and why it matters.

Rather than seeing AI as a threat, we could see it as an invitation. An invitation to evolve, to collaborate, and to reimagine. Whatever the form of Da Vinci's research into optics or Anadol's data paintings, the history of art and technology has never been one of evolution and redesign.