In the mid-19th century, governments and military institutions began actively employing photographers during conflicts to document their war efforts, images that were then used to cultivate a sense of national pride back home. Two well-known examples are Roger Fenton’s photographs of the Crimean War and Matthew Brady’s photographs of the American Civil War.

However, by the 20th century, with the rise of World War II, the technological boom, and the growing need for mass communication on a global scale, conflict photography began to shift toward a more raw and activist approach. It became widely used as a medium to expose concealed truths and reveal the horrors of war. This transformation became particularly prominent during the Vietnam War, where the power of photographic imagery played a central role in shaping public opinion and confronting audiences with the brutal realities of the conflict.

One of the most characteristic examples is Nick Ut’s photograph of Phan Thị Kim Phúc taken in 1972, the nine-year-old girl captured running naked and screaming after a napalm attack, which became one of the most recognizable war images in history.

With this shift, especially in today’s world, where we are surrounded by ongoing wars and a multitude of media coverage, many questions arise: What is the responsibility of the viewer when looking at such images? What are the different ways of seeing, and what do they signify?

How presentation shapes seeing

The act of seeing war photographs—and photographs of victims—is an action that has many layers. It is a political and social act in itself, one that depends heavily on the reason behind looking at these specific images and on the response and reaction we have when engaging in this action. It can be an act of passive consumption and objectification or one of ethical engagement. It carries a weight of responsibility—almost equivalent, dare I say, to the responsibility of the author of the images (the photographer) and those involved in their presentation, be they curators, journalists, or others.

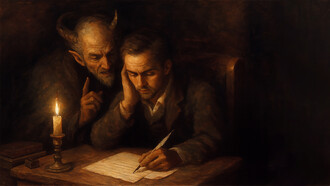

The act of seeing activates a range of responses that are deeply rooted in our subconscious and shaped by external stimuli such as cultural and societal frameworks. These reactions are heavily influenced by the context in which these photographs are shown—the choices of documentation and the narrative the photographer, curator, or publishing agency seeks to communicate. What is the purpose behind showing these photographs? Is it to raise awareness? To elicit emotion? To inform or provoke? These questions are essential to how we interpret what we see.

The setting in which these images are presented plays a significant role in shaping our response. Are they installed in a gallery, and if so, what is the purpose of the exhibition? (A highly problematic context, especially when presented for aesthetic pleasure or framed purely as works of art.) Or are they shown as part of a news segment on television, followed immediately by a commercial for a new face cream that combats aging? The discord in such juxtapositions speaks volumes about our culture of consumption and the commodification of pain.

Irresponsible visual consumption

After studying theorists such as Susan Sontag, Julian Stallabrass, Jean Baudrillard, and John Berger, among others, I have come to the conclusion that there are four main forms of irresponsible visual consumption: aversion, fetishization, desensitization, and dissociation.

This tendency is especially relevant today, as we live in a time when media platforms frequently present conflict imagery in a sensationalist manner. In this context, sensationalism refers to the presentation of images in a way that prioritizes emotional provocation over respectful or informative representation. The image is used primarily to seize the viewer’s attention rather than to foster understanding or ethical engagement.

Sensationalist imagery often detaches the photograph from its socio-political background, presenting suffering without sufficiently addressing its causes or context. In doing so, it reduces complex realities of conflict and trauma to raw visual consumption, which can lead the viewer to respond with aversion or fetishization, both rooted in an emotionally charged yet ethically disengaged form of viewing.

Aversion is triggered by a feeling of shock and is often followed by anger or disgust toward the subject of the image or the context it evokes. It is not rooted in emotional detachment, like dissociation or desensitization, but rather in emotional intensity. When the viewer’s moral or emotional boundaries are confronted, the reaction is often one of immediate withdrawal—a kind of psychological “flight” response, driven by the need to escape emotional overload. Without appropriate mechanisms for coping or reflection, this response can leave the viewer unable to process what they have seen. It frequently leads to feelings of helplessness and despair—emotions that may linger briefly, only to be replaced by forgetfulness. Such reactions are especially provoked when conflict is presented with the explicit aim of inducing shock.

Sensationalism can, in turn, provoke another reaction: fetishization. Here, a kind of unexplained excitement or curiosity arises when looking at such images. The viewer’s gaze seeks emotional stimulation, shock, or exoticism rather than understanding. When I refer to fetishization in this context, I do not mean that the viewer actively enjoys seeing such imagery, but rather that they find themselves drawn to these images, compelled by the trauma of others in a way that ultimately centers their own emotional experience rather than the subject’s reality.

This phenomenon is described powerfully by scholar Joanna Bourke, who uses the term “pornography of pain” to capture how images of suffering are consumed for their visceral impact. It is not unnatural, nor illogical, that viewers sometimes derive pleasure from these images, whether aesthetic, emotional, or voyeuristic. However, the important thing is to recognize that pleasure and to direct it toward critical thought and solidarity, not passive or morbid consumption.

The next reaction, desensitization—or, in other words, apathy—is often the byproduct of the phenomenon described as “the saturation of the image.” It is the manifestation of an emotional disability: a feeling of numbness and indifference that arises when repeated exposure to images of suffering dulls the viewer’s capacity to react.

Several critics have examined desensitization in relation to the saturation of the image, the most prominent being Susan Sontag, especially through her seminal works On Photography (1977) and Regarding the Pain of Others (2003). In her writings, Sontag discusses the consequences of a society inundated with visual representations of war and suffering. She argues that continual exposure to such images can weaken their emotional impact, where the initial shock gives way to apathy. While she acknowledges that photographs hold the power to inform and evoke empathy, she warns that their overabundance, and our overexposure, may ultimately numb our capacity to respond meaningfully.

Lastly, looking at conflict photographs can evoke a state of dissociation. This behavior is often accompanied by a feeling of relief—relief that it is they suffering and not us, because the conflict is happening somewhere geographically distant. And if it is not geographically distant, we find other ways to disassociate from the suffering: religious, cultural, or political differences that create distance between ourselves and the subject.

These factors combine to reinforce the concept of the other—a construct that justifies our ultimate inaction and feeds the illusion that we are separate from the sufferer’s reality. The lens through which we empathize is far from neutral; it shifts depending on where we are, what identities we hold, and how geopolitical narratives shape our perception. The empathy extended toward those suffering in Ukraine, Syria, or Gaza, for example, can vary dramatically depending on the viewer’s own national, religious, cultural, or ideological standpoint.

The choice not to see

On the other hand, the deliberate and active choice of not seeing signifies an intolerance and an inability to digest what is portrayed. It is a conscious response to images whose horrors are too overwhelming to bear. But what is it about an image, an object, that makes it so unbearable that we cannot—or refuse to—look at it? The answer is simpler than one might expect, but far more shameful when confessed or realized.

We turn away because we are afraid—afraid of feeling despair, helplessness, and, most of all, of recognizing ourselves in the people or the places depicted. We are terrified of the thought, “These could be my children, my parents, my home,” or even, “This could be me.” In turning away, we prioritize ourselves, justifying the decision as a mechanism of self-protection. But what are we protecting ourselves from? From being confronted with reality? From the harsh truth that our daily lives, which we work so hard to keep intact, are not immune to such suffering?

The instinctive—or informed—decision to turn away from images of suffering is, at its root, selfish. We prioritize the comfort of ignorance over the discomfort of knowing. By choosing not to see, we protect ourselves from the emotional weight of confronting reality, but we also accept the burden of responsibility for being complacent and passive in the face of suffering. We choose to look away not because we cannot bear the image, but because we cannot bear what it reveals about ourselves—and, ultimately, about the fragility of the world we live in.