In the world of programming and game design, Godot is an open-source game engine that allows developers to create both 2D and 3D games. Unlike other engines like Unity or Unreal, Godot is known for its simplicity and versatility. It was designed to be easily used by beginners, but it also offers advanced features for experienced developers. The engine supports various programming languages, but its primary language is GDScript, a Python-like language that allows developers to quickly and efficiently write game logic.

The origin of the name and its connection to Beckett

The choice of the name "Godot" for the engine is not accidental: it references Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot, one of the most famous works of 20th-century theater. But what is the connection between a game engine and an existential drama? And how can Beckett’s philosophy align with programming and scripting?

Godot, in essence, is a tool for building virtual worlds. Developers create interactive environments in which the player can explore, interact, and influence the narrative. In a game made with Godot, the player’s actions are crucial: their interaction with the environment determines how the story unfolds. This is the essence of "gameplay": the player is not just a passive spectator but the protagonist who shapes the virtual world.

The theme of waiting, repetition, and non-action as a narrative element

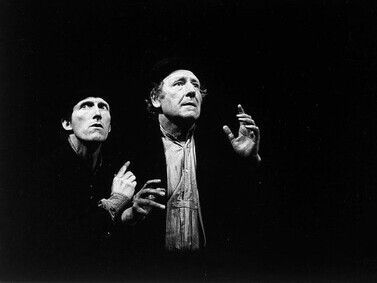

How does all this connect to Beckett's theater and Waiting for Godot? The answer lies in the interwoven concepts of waiting, repetition, and non-action. In Beckett’s play, protagonists Vladimir and Estragon are trapped in an endless cycle of anticipation, waiting for a mysterious figure who never arrives. This suspension of time—marked by repetition, boredom, and the gradual passage of moments—is the driving force of the drama. Similarly, in game design, repetition is not merely a series of actions leading to a final result; it often forms a loop in which the player repeatedly explores the virtual world, seeking novelty or meaning.

Godot, as a game engine, creates environments where waiting and non-action are not voids but narrative resources. In this digital realm, idle moments transform into spaces for reflection, mirroring Beckett’s minimalist style where characters are caught in cycles of inaction and introspection. With its intuitive GDScript language, Godot empowers developers to design worlds that incorporate these pauses—using waiting and repetition to engage players and stimulate active reflection. Thus, waiting, repetition, and non-action emerge as powerful narrative elements, defining both the absurd theater of Beckett and the immersive experience of interactive games.

The concept of "presence-absence" and the digital metaphor

The name Godot for a game engine evokes the idea of presence-absence, much like in Beckett’s play. In the theatre of the absurd, Godot is the anticipated figure who never arrives, while in game design, the engine is the invisible structure that enables interaction yet remains unseen by the player.

Similarly, in scripting, many instructions exist in a state of waiting, only activating when triggered by an event, echoing the cycle of suspension and repetition in the play. Moreover, while the player appears free to explore, they are ultimately bound by the rules set by the code, just like Beckett’s characters, trapped in a predefined world. In this sense, the name Godot is not just a literary reference but a metaphor for the very nature of digital interaction: a reality that exists only when it is experienced.

An aesthetic parallel: the 2001 film and the virtual world

In this context, the aesthetic of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, particularly in the 2001 film adaptation, becomes even more relevant. The protagonists seem trapped in a desolate landscape under a monochromatic, artificial sky, where the background feels empty and plastic. This visual environment mirrors the virtual worlds created in games, where players navigate through digital landscapes that are both vast and yet inherently controlled, offering only the illusion of freedom. Much like Beckett’s characters, who appear lost in a world that seems both real and unreal, video game players are immersed in environments that, while interactive, are ultimately constructed and confined by the rules of the code, much like the waiting and non-action of Beckett's theatre. In both cases, reality is an illusion, defined by what is presented—and what is absent.

The role of scripting in Godot

Scripting in Godot is based on GDScript, a language that allows developers to write the logic of the game, from simple animations to complex interactions between objects or characters. With GDScript, a developer can decide what happens, when, and why. The language is designed to be intuitive, fast, and perfectly integrated with the engine’s interface, making game programming a smooth experience.

The Godot code (primarily written in GDScript, but also in C#, C++, and other languages) is responsible for managing every aspect of a game: logic, interactions, animations, physics, and rendering. Some fundamental things that Godot code does in practice are controlling game flow—it decides what happens at any given moment, managing states and transitions (e.g., when a character jumps, the code activates gravity to bring them back down)—and using loops and conditions to determine events.

Language, code, and the philosophy of precision

The choice of the name Godot for a game engine is no coincidence. Beckett, in his theater of the absurd, reduces language to its essentials, eliminating the superfluous and leaving only words laden with meaning. The same principle applies to programming: every line of code must serve a precise function, with no waste. GDScript, the primary language of Godot, follows this philosophy with a streamlined, straightforward syntax designed to be intuitive and efficient. Just as Beckett plays with emptiness and waiting to give meaning to absence, the code in a game engine creates interactive worlds by reducing every instruction to what is essential. In both cases, language becomes a creative act that defines the space and time of the experience.

The role of the player: actor or spectator?

In theater, the actor brings the text to life, while the audience, through interpretation, completes the experience. Similarly, in games, the player is the central figure, but the game provides the "scenery," shaping the environment where the narrative unfolds. In Godot, the interaction between player and game world is key: every action the player takes can influence the plot. Much like theater, where the story evolves through characters and direction, the player's choices guide the experience in a game. In Godot, the player becomes an "actor" within a virtual world, shaping the narrative by responding and adapting to its rules. This mirrors Beckett's theater, where the audience impacts emotional interpretation. In both cases, the individual has an active role yet is still part of a world governed by pre-established structures—whether in the form of stage direction or game mechanics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, both the Godot engine and Waiting for Godot invite reflection on waiting, repetition, and the human experience. Interactive games and theater share similar narrative elements, especially in how interaction—or its absence—helps shape the meaning of the experience. With Godot, waiting is not just an abstract concept but an integral part of the creative process. Just as in Beckett's theater, where waiting serves as a metaphor for the human condition, in games waiting can become a powerful tool for exploring interaction and reflection. Therefore, Godot is not just a game engine: it is also an invitation to explore how "non-action" can become a narrative opportunity, just as it does in the waiting that permeates Beckett’s theatrical work.