After World War II, the city of Amsterdam had fallen into a state of devastation and destruction. The destruction remained a huge number of “cavities”—namely”, the informal space, such as the unused vacant plot between buildings, dumping land, or even spaces that were surrounded by ramshackle. Also, the Dutch were dissatisfied with both the housing conditions and the shortage quantity of that, which could not meet the community demand. Leaving Amsterdam with an explosion number of babies was one of the consequences of the world war.

And, thus, serial questions are raised: “Where and which space could be imprinted on those Amsterdam children’s childhood memories, especially for those who were born and raised up during the post-war period?”. A silence of sound might be the answer, or it can be said soundlessly in one mind: “Poor them! They had childhood trauma about their spatial memories of the city images that belong to the past.”

Noticing the predominance of informal spaces in Amsterdam at that time over public spaces. Also, the necessity of recovery and eradicating war memories for the residents was of paramount. Aldo van Eyck—a Dutch architect—observed potentially how these areas flourished as focal points for community gatherings and social interactions during a period marked by destruction.

Aldo Van Eyck worked for the Urban Development Department of Amsterdam; and as soon as he practiced in his studio, he started designing playgrounds as a healing destination to both the damaged urban landscape and the sensitive souls of children who had endured the post-war period. His act posed a sense of humanity but also showcased a strong resistance towards functionalism at that time within his architectural interventions. Even though he was an active member of CIAM (International Congresses of Modern Architecture), he criticized the town planning that was shaped by functionalism, in which either the originality or humanity was restrictive. A shift towards structuralism found him in a greater possibility in aligning his architecture that was applicable for human-scale, borderless imagination and relativity.

From the small scale of the typology of modular installation to the large scale of the city as a playground, the Dutch architect pulled Amsterdam to a distinct side within the era that was full of efforts to make this city a Functionalist City. It was initially planned to modernize the city through systematic urban planning—called the General Expansion Plan (1935), characterized by a top-down approach that prioritized efficiency and order, requiring high hierarchy. Some controversial acts such as considering deconstructing the Jordaan and the Nieuwmarktbuurt in order to reprogram and force them to be more adaptive to the functionalism. However, the deconstructive interventions were met with refutation from residents, many of whom viewed them as disruptive to local traditions and identities.

The final decision was to cancel the plan, due to the pressure from the profound and aggressive protests. The city center was undetected in an unexplainable way; meanwhile, this was the area where it needed most of the restoration. Van Eyck jumped in to save Amsterdam through his modest plan with the bottom-up architecture approaches. The users’ behaviors have turned it out to be suitable and applicable for such a sensitive city that had just undergone the most disheartening historical event. His soft response through the frameworks of playground created the imagination of space and opposed strongly to the Functionalism. In a Dutch magazine, Forum, Van Eyck stated:

“Functionalism has killed creativity; it leads to a cold technocracy in which the human aspect is forgotten. A building is more than a sum of its functions; architecture has to facilitate human activity and promote social interaction.”

To an extent, Van Eyck wrote his own poetic of space and architecture, to stitch up the wound caused by the war. Even though it could be judged that it was a weird architectural taste, it was effective to blend in and connect with the urban fabric. And for the most part, the children's behavior was captured with the joyfulness, for which that prior war was impossible to deliver.

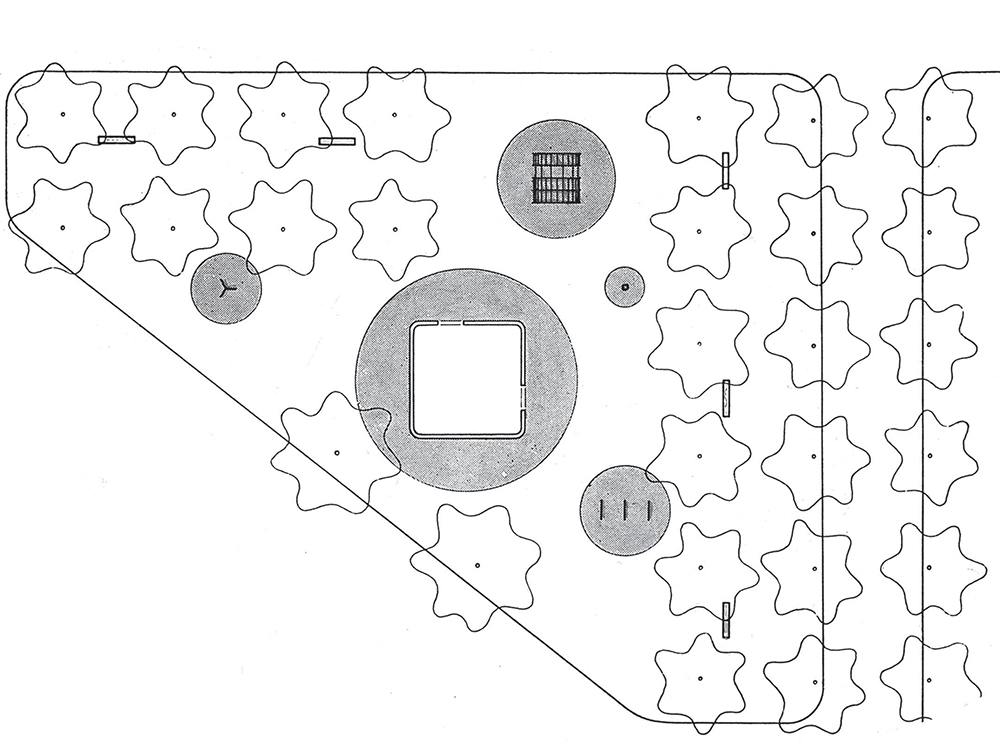

Plan of playground at Jacob Thijsseplein (1949-1950), © Archive Aldo + Hannie van Eyck Foundation.

His architecture of the playground drove him to his architectural experiment and philosophy—relativity and imagination. Relativity, in the architectural sense, can be loosely defined as the relationship between space, time, and the experiencer. Van Eyck elaborated on this phenomenon by demonstrating the reciprocal relationship among those factors, rather than emphasizing the one-way relationship, which was composed of “a central hierarchical ordering principle". Non-hierarchy was examined as a premise for his framework over the network of playgrounds. He did not only focus on the design configuration, as his equipment display and pose in such a simple language, but instead the encouragement of the children’s imagination and foster a sense of stimulation.

He designed a catalog of playgrounds, including the geometric concrete sand pit, frames, climbing domes/arches, and stepping stones. Later, scattered those elements around the center of Amsterdam and made his design the city identity, which successfully extended to a broader context of urban play. The sandpit was highlighted as the central element, balanced by other subordinate objects. The frames were usually molded out of galvanized steel tubes of 4 cm, transformed in a linear or circular direction. They were more or less alike to the gymnasium equipment.

His playground elements leave a completely open mind for children when it comes to the play process. One of the most typical practices to strengthen his design thinking is the user’s behavior of the climbing domes. This hemispherical steel installation was not something that children could only climb over. Children possibly sit inside, eat, talk, and view the city through the steel bar under the effect of the cityscape. The dome was not fully covered as a shelter, but it was designed to be semi-tangible by the effect of the frames of the dome’s ribs. This had successfully impelled the minds of the children as the answers were responded to along with their interaction with the playset. Sometimes, it is said that great architecture happens when the architect makes it effortlessly.

Can his work be categorized as architecture or merely an installation? At the same time, architecture fundamentally comprises essential elements that establish the foundation for spatial formation. For instance, at its core, any architectural design must include a foundational platform and structural dividers to create enclosed spaces. Perhaps it is a yes from me; in the end, he still forms a space for human interaction within the urban public. This work indeed qualifies as architecture, as it successfully creates a space conducive to human engagement within the urban public domain. It lies on the differences of his methodologies when forming a space. Instead of placing objects within a pre-existing framework, the work focuses on creating an environment where the space itself becomes the medium through which residents can interact and experience their surroundings.

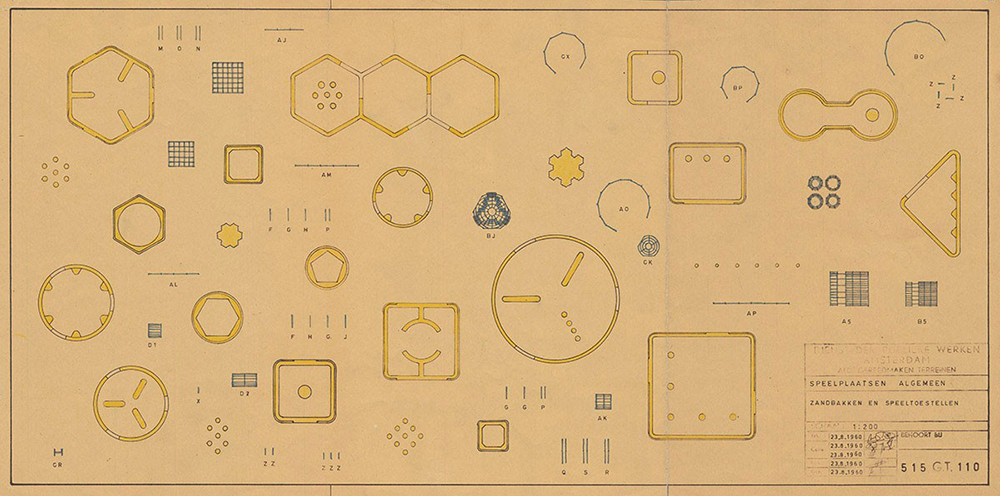

His catalog of playground equipment carries a sense of children's expression of drawings, yet it also resonates closely with primitive art forms, suggesting a primal, intuitive connection to elemental shapes and patterns. The simplicity and purity found in Van Eyck’s design principles—his use of elementary geometry and transformations among basic forms—offer a correlation between the imagination in the flat world of his drawing and the three-dimensional objects. His paper designs, though intricate, seem to emerge from a field of conditions where geometric elements are repeated and recombined to create variations that defy the language of playgrounds that is covered up by structuralism. The interplay between simplicity and complexity, primal and refined, creates a work that feels both timeless and deeply contextualized within its environment.

Illustration for the playground catalog for the Department of Public Works, © Archive Aldo, Hannie van Eyck Foundation.

Over six hundred playgrounds had been designed and scattered around the center city of Amsterdam. This makes his design a city identity of Amsterdam. These sites have become emotionally charged landscapes for many, serving as constant reminders of the trauma and losses incurred during the post-war period. The catalogue, or the framework of the architecture of the playground by Aldo van Eyck, displays his orientation towards structuralism, where human scale and creativity have been determined as a primal importance. Putting aside the burden with the functional program.

Notes

Eyck, A. v. (1959). Het Verhaal van ên Andere Gedachte' (The story of Another Thought). Forum 7/1959, Amsterdam and Hilversum.

Eyck, A. v., Ingeborg, R. d., & Lafaivre , L. (2002). The Playgrounds and the City. NAi.