In the work of the Korean artist Choo Kyung, the construct of her paintings appears to strive toward unity by way of nature. Her perspective remains clear. This would suggest that the physicality of her abstraction exists within the context of a realist sensibility. One is not necessarily removed from the other. In her paintings, she removes herself arbitrarily from imposed distances that separate the body from time and space, which, throughout East Asia, are considered essential ingredients in painting. This, in turn, further removes Choo Kyung from imposing a desire that leads towards an unnecessary end-result. Rather her focus is perceptively given to a sense of unity where nature is her guide. It is here the artist embraces living and working in the present tense. It is here the flame resides. It is here Choo Kyung discovers the linguistic interlude that captures the transformation of non-Being into Being. It is here the flame defines her space and time.

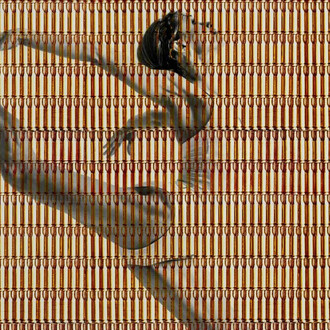

Choo Kyung offers a multiplicity of layers in her paintings wherein different applications of material are definitively placed one over another. The artist begins with a layer of “stone dust” prior to applying a monochrome coat of acrylic paint on canvas. This is followed by another binder brushed over the painted surface whereupon the application of Hanji paper is directly adhered. Occasionally the Hanji is coated in charcoal powder as shown in Choo Kyung’s series, titled Flame – Embracing Nature. Her concept is borrowed directly from nature whereby an invisible painting is then applied with water, which is followed by a culmination of fire over Hanji through the artist’s manipulation of a blowtorch. According to the artist, “Fire generates a new world over the canvas” whereupon “a new scene appears and disappears between the flames.” Choo Kyung’s paintings are “strongly sculptural in nature” – a statement that can be interpreted from two points of view: one, the manner of production involved in layering her paintings as if to suggest a systemic physicality of work coincident with that of sculpture; and two, the artist’s reference to motifs found in nature – earth, water, fire, and wind – that maintain a presence exceeding the necessity of a two- dimensional simulation, thereby moving the construct into the realm of three, if not four dimensions.

The Hanji paper (originally processed from mulberry bark), returns to its original status by way of the flame, signified through the force of nature. The genius of nature is the genius of art. They interact with one another. For Choo Kyung, they are representations, contingent on the flame in which the force of nature has been regained. Nature and art have returned to one another. The artist’s memory constitutes something close to the Jungian concept wherein the “collective unconscious” transmits energy (qi) from one artist to another, each with their own turn, each with their own biography, and their own relationship to nature. Choo Kyung refers to “a figuration of the breath or souls of living things through fire and flames.” The key to her paintings Is the flame, the undercurrent of the artist who seeks the mystery of the universe within herself. The prescription is the Hanji on canvas, the source of energy that keeps her moving through space and time.

(By Art Critic Robert C. Morgan)